I want a red dress. I want it flimsy and cheap, I want it too tight, I want to wear it until someone tears it off me. I want it sleeveless and backless, this dress, so no one has to guess what’s underneath. I want to walk down the street past Thrifty’s and the hardware store with all those keys glittering in the window, past Mr. and Mrs. Wong selling day-old donuts in their café, past the Guerra brothers slinging pigs from the truck and onto the dolly, hoisting the slick snouts over their shoulders. I want to walk like I’m the only woman on earth and I can have my pick. I want that red dress bad. I want it to confirm your worst fears about me, to show you how little I care about you or anything except what I want. When I find it, I’ll pull that garment from its hanger like I’m choosing a body to carry me into this world, through the birth-cries and the love-cries too, and I’ll wear it like bones, like skin, it’ll be the goddamned dress they bury me in.

From Tell Me by Kim Addonizio. Copyright © 2000 by Kim Addonizio. Reprinted by permission of BOA Editions, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Our conversation is a wing below my consciousness, like organization in blowing cloth, eddies of water, its order of light on film with no lens.

A higher resonance of story finds its way to higher organization: data swirl into group dreams.

Then story surfaces, as if recognized; flies buzzing in your room suddenly translate to "Oh! You're crying!"

So, here I hug the old person, who's not "light" until I embrace him.

My happiness at seeing him, my French suit constitute at the interface of wing and occasion.

Postulate whether the friendship is fulfilling.

Reduce by small increments your worry about the nature of compassion or the chill of emotional identification among girlfriends, your wish to be held in the consciousness of another, like a person waiting for you to wake.

Postulate the wave nature of wanting him to wait (white space) and the quanta of fractal conflict, point to point, along the outline of a petal, shore from a small boat.

Words spoken with force create particles.

He calls the location of accidents a morphic field; their recurrence is resonance, as of an archetype with the vibration of a seed.

My last thoughts were bitter and helpless.

Friends witnessing grief enter your consciousness, illuminating your form, so quiet comes.

From Concordance, poems by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, visual images by Kiki Smith. Copyright © 2006 by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Kelsey Street Press. Used by permission.

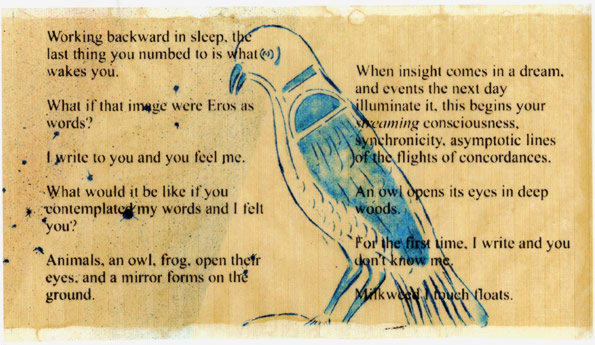

Poem by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

Illustration by Kiki Smith

Working backward in sleep, the

last thing you numbed to is what

wakes you.

What if that image were Eros as

words?

What would it be like if you

contemplated my words and I felt

you?

Animals, an owl, frog, open their

eyes, and a mirror forms on the

ground.

When insight comes in a dream,

and events the next day

illuminate it, this begins your

streaming consciousness,

synchronicity, asymptotic lines

of the flights of concordances.

An owl opens its eyes in deep

woods.

For the first time, I write and you

don't know me.

Milkweed I touch floats.

From Concordance by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Kiki Smith. Published by the Rutgers Center for Innovative Print and Paper.

There was a time I could say no one I knew well had died. This is not to suggest no one died. When I was eight my mother became pregnant. She went to the hospital to give birth and returned without the baby. Where’s the baby? we asked. Did she shrug? She was the kind of woman who liked to shrug; deep within her was an everlasting shrug. That didn’t seem like a death. The years went by and people only died on television—if they weren’t Black, they were wearing black or were terminally ill. Then I returned home from school one day and saw my father sitting on the steps of our home. He had a look that was unfamiliar; it was flooded, so leaking. I climbed the steps as far away from him as I could get. He was breaking or broken. Or, to be more precise, he looked to me like someone understanding his aloneness. Loneliness. His mother was dead. I’d never met her. It meant a trip back home for him. When he returned he spoke neither about the airplane nor the funeral.

Every movie I saw while in the third grade compelled me to ask, Is he dead? Is she dead? Because the characters often live against all odds it is the actors whose mortality concerned me. If it were an old, black-and-white film, whoever was around would answer yes. Months later the actor would show up on some latenight talk show to promote his latest efforts. I would turn and say—one always turns to say—You said he was dead. And the misinformed would claim, I never said he was dead. Yes, you did. No, I didn’t. Inevitably we get older; whoever is still with us says, Stop asking me that.

Or one begins asking oneself that same question differently. Am I dead? Though this question at no time explicitly translates into Should I be dead, eventually the suicide hotline is called. You are, as usual, watching television, the eight-o’clock movie, when a number flashes on the screen: 1-800-SUICIDE. You dial the number. Do you feel like killing yourself? the man on the other end of the receiver asks. You tell him, I feel like I am already dead. When he makes no response you add, I am in death’s position. He finally says, Don’t believe what you are thinking and feeling. Then he asks, Where do you live?

Fifteen minutes later the doorbell rings. You explain to the ambulance attendant that you had a momentary lapse of happily. The noun, happiness, is a static state of some Platonic ideal you know better than to pursue. Your modifying process had happily or unhappily experienced a momentary pause. This kind of thing happens, perhaps is still happening. He shrugs and in turn explains that you need to come quietly or he will have to restrain you. If he is forced to restrain you, he will have to report that he is forced to restrain you. It is this simple: Resistance will only make matters more difficult. Any resistance will only make matters worse. By law, I will have to restrain you. His tone suggests that you should try to understand the difficulty in which he finds himself. This is further disorienting. I am fine! Can’t you see that! You climb into the ambulance unassisted.

Excerpt from Don’t Let Me Be Lonely copyright © 2004 by Claudia Rankine. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota. All rights reserved.

On the bus two women argue about whether Rudy Giuliani had to kneel before the Queen of England when he was knighted. One says she is sure he had to. They all had to, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Mick Jagger. They all had to. The other one says that if Giuliani did they would have seen it on television. We would have seen him do it. I am telling you we would have seen it happen.

When my stop arrives I am still considering Giuliani as nobility. It is difficult to separate him out from the extremes connected to the city over the years of his mayorship. Still, a day after the attack on the World Trade Center a reporter asked him to estimate the number of dead. His reply—More than we can bear—caused me to turn and look at him as if for the first time. It is true that we carry the idea of us along with us. And then there are three thousand of us dead and it is incomprehensible and ungraspable. Physically and emotionally we cannot bear it, should in fact never have this capacity. So when the number is released it is a sieve that cannot hold the loss of us, the loss Giuliani recognized and answered for.

Wallace Stevens wrote that “the peculiarity of the imagination is nobility . . . nobility which is our spiritual height and depth; and while I know how difficult it is to express it, nevertheless I am bound to give a sense of it. Nothing could be more evasive and inaccessible. Nothing distorts itself and seeks disguise more quickly. There is a shame of disclosing it and in its definite presentation a horror of it. But there it is.”

Sir Giuliani kneeling. It was apparently not something to be seen on television, but rather a moment to be heard and experienced; a moment that allowed his imagination’s encounter with death to kneel under the weight of the real.

Excerpt from Don't Let Me Be Lonely, Copyright © 2004 by Claudia Rankine. Used by permission of Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota. All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org

For Naomi Ginsberg, 1894-1956

Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village. downtown Manhattan, clear winter noon, and I've been up all night, talking, talking, reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues shout blind on the phonograph the rhythm the rhythm—and your memory in my head three years after— And read Adonais' last triumphant stanzas aloud—wept, realizing how we suffer— And how Death is that remedy all singers dream of, sing, remember, prophesy as in the Hebrew Anthem, or the Buddhist Book of An- swers—and my own imagination of a withered leaf—at dawn— Dreaming back thru life, Your time—and mine accelerating toward Apoca- lypse, the final moment—the flower burning in the Day—and what comes after, looking back on the mind itself that saw an American city a flash away, and the great dream of Me or China, or you and a phantom Russia, or a crumpled bed that never existed— like a poem in the dark—escaped back to Oblivion— No more to say, and nothing to weep for but the Beings in the Dream, trapped in its disappearance, sighing, screaming with it, buying and selling pieces of phantom, worship- ping each other, worshipping the God included in it all—longing or inevitability?—while it lasts, a Vision—anything more? It leaps about me, as I go out and walk the street, look back over my shoulder, Seventh Avenue, the battlements of window office buildings shoul- dering each other high, under a cloud, tall as the sky an instant—and the sky above—an old blue place. or down the Avenue to the south, to—as I walk toward the Lower East Side —where you walked 50 years ago, little girl—from Russia, eating the first poisonous tomatoes of America frightened on the dock then struggling in the crowds of Orchard Street toward what?—toward Newark— toward candy store, first home-made sodas of the century, hand-churned ice cream in backroom on musty brownfloor boards— Toward education marriage nervous breakdown, operation, teaching school, and learning to be mad, in a dream—what is this life? Toward the Key in the window—and the great Key lays its head of light on top of Manhattan, and over the floor, and lays down on the sidewalk—in a single vast beam, moving, as I walk down First toward the Yiddish Theater—and the place of poverty you knew, and I know, but without caring now—Strange to have moved thru Paterson, and the West, and Europe and here again, with the cries of Spaniards now in the doorstops doors and dark boys on the street, fire escapes old as you —Tho you're not old now, that's left here with me— Myself, anyhow, maybe as old as the universe—and I guess that dies with us—enough to cancel all that comes--What came is gone forever every time— That's good! That leaves it open for no regret—no fear radiators, lacklove, torture even toothache in the end— Though while it comes it is a lion that eats the soul—and the lamb, the soul, in us, alas, offering itself in sacrifice to change's fierce hunger--hair and teeth—and the roar of bonepain, skull bare, break rib, rot-skin, braintricked Implacability. Ai! ai! we do worse! We are in a fix! And you're out, Death let you out, Death had the Mercy, you're done with your century, done with God, done with the path thru it—Done with yourself at last—Pure —Back to the Babe dark before your Father, before us all—before the world— There, rest. No more suffering for you. I know where you've gone, it's good. No more flowers in the summer fields of New York, no joy now, no more fear of Louis, and no more of his sweetness and glasses, his high school decades, debts, loves, frightened telephone calls, conception beds, relatives, hands— No more of sister Elanor,—she gone before you—we kept it secret you killed her--or she killed herself to bear with you—an arthritic heart —But Death's killed you both—No matter— Nor your memory of your mother, 1915 tears in silent movies weeks and weeks—forgetting, agrieve watching Marie Dressler address human- ity, Chaplin dance in youth, or Boris Godunov, Chaliapin's at the Met, halling his voice of a weeping Czar —by standing room with Elanor & Max—watching also the Capital ists take seats in Orchestra, white furs, diamonds, with the YPSL's hitch-hiking thru Pennsylvania, in black baggy gym skirts pants, photograph of 4 girls holding each other round the waste, and laughing eye, too coy, virginal solitude of 1920 all girls grown old, or dead now, and that long hair in the grave—lucky to have husbands later— You made it—I came too—Eugene my brother before (still grieving now and will gream on to his last stiff hand, as he goes thru his cancer—or kill —later perhaps—soon he will think—) And it's the last moment I remember, which I see them all, thru myself, now --tho not you I didn't foresee what you felt--what more hideous gape of bad mouth came first--to you--and were you prepared? To go where? In that Dark--that--in that God? a radiance? A Lord in the Void? Like an eye in the black cloud in a dream? Adonoi at last, with you? Beyond my remembrance! Incapable to guess! Not merely the yellow skull in the grave, or a box of worm dust, and a stained ribbon—Deaths- head with Halo? can you believe it? Is it only the sun that shines once for the mind, only the flash of existence, than none ever was? Nothing beyond what we have—what you had—that so pitiful—yet Tri- umph, to have been here, and changed, like a tree, broken, or flower—fed to the ground—but made, with its petals, colored, thinking Great Universe, shaken, cut in the head, leaf stript, hid in an egg crate hospital, cloth wrapped, sore—freaked in the moon brain, Naughtless. No flower like that flower, which knew itself in the garden, and fought the knife—lost Cut down by an idiot Snowman's icy—even in the Spring—strange ghost thought some—Death—Sharp icicle in his hand—crowned with old roses—a dog for his eyes—cock of a sweatshop—heart of electric irons. All the accumulations of life, that wear us out—clocks, bodies, consciousness, shoes, breasts—begotten sons—your Communism—'Paranoia' into hospitals. You once kicked Elanor in the leg, she died of heart failure later. You of stroke. Asleep? within a year, the two of you, sisters in death. Is Elanor happy? Max grieves alive in an office on Lower Broadway, lone large mustache over midnight Accountings, not sure. His life passes—as he sees—and what does he doubt now? Still dream of making money, or that might have made money, hired nurse, had children, found even your Im- mortality, Naomi? I'll see him soon. Now I've got to cut through to talk to you as I didn't when you had a mouth. Forever. And we're bound for that, Forever like Emily Dickinson's horses —headed to the End. They know the way—These Steeds—run faster than we think—it's our own life they cross—and take with them. Magnificent, mourned no more, marred of heart, mind behind, mar- ried dreamed, mortal changed—Ass and face done with murder. In the world, given, flower maddened, made no Utopia, shut under pine, almed in Earth, blamed in Lone, Jehovah, accept. Nameless, One Faced, Forever beyond me, beginningless, endless, Father in death. Tho I am not there for this Prophecy, I am unmarried, I'm hymnless, I'm Heavenless, headless in blisshood I would still adore Thee, Heaven, after Death, only One blessed in Nothingness, not light or darkness, Dayless Eternity— Take this, this Psalm, from me, burst from my hand in a day, some of my Time, now given to Nothing—to praise Thee—But Death This is the end, the redemption from Wilderness, way for the Won- derer, House sought for All, black handkerchief washed clean by weeping —page beyond Psalm—Last change of mine and Naomi—to God's perfect Darkness--Death, stay thy phantoms! II Over and over—refrain—of the Hospitals—still haven't written your history—leave it abstract—a few images run thru the mind—like the saxophone chorus of houses and years— remembrance of electrical shocks. By long nites as a child in Paterson apartment, watching over your nervousness—you were fat—your next move— By that afternoon I stayed home from school to take care of you— once and for all—when I vowed forever that once man disagreed with my opinion of the cosmos, I was lost— By my later burden—vow to illuminate mankind—this is release of particulars—(mad as you)—(sanity a trick of agreement)— But you stared out the window on the Broadway Church corner, and spied a mystical assassin from Newark, So phoned the Doctor—'OK go way for a rest'—so I put on my coat and walked you downstreet—On the way a grammarschool boy screamed, unaccountably—'Where you goin Lady to Death'? I shuddered— and you covered your nose with motheaten fur collar, gas mask against poison sneaked into downtown atmosphere, sprayed by Grandma— And was the driver of the cheesebox Public Service bus a member of the gang? You shuddered at his face, I could hardly get you on—to New York, very Times Square, to grab another Greyhound—

From Collected Poems 1947-1980 by Allen Ginsberg, published by Harper & Row. Copyright © 1984 by Allen Ginsberg. Used with permission.

"Sleeping so? Thou hast forgotten me, Akhilleus. Never was I uncared for in life but am in death. Accord me burial in all haste: let me pass the gates of Death. Shades that are images of used-up men motion me away, will not receive me among their hosts beyond the river. I wander about the wide gates and the hall of Death. Give me your hand. I sorrow. When thou shalt have allotted me my fire I will not fare here from the dark again. As living men we'll no more sit apart from our companions, making plans. The day of wrath appointed for me at my birth engulfed and took me down. Thou too, Akhilleus, face iron destiny, godlike as thou art, to die under the wall of highborn Trojans. One more message, one behest, I leave thee: not to inter my bones apart from thine but close together, as we grew together, in thy family's hall. Menoitios from Opoeis had brought me, under a cloud, a boy still, on the day I killed the son of Lord Amphídamas--though I wished it not-- in childish anger over a game of dice. Pêleus, master of horse, adopted me and reared me kindly, naming me your squire. So may the same urn hide our bones, the one of gold your gracious mother gave."

Lines 80-106 from "A Friend Consigned to Death" in The Iliad by Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald. Translation copyright © 1974 by Robert Fitzgerald. Copyright © 2004 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved.

* First: The blinding of the citizens Second: The common plague of worms (like lute strings, they must be plucked and the wounds spread with fresh butter) Then: This amorousness * Old woman cried and was fed her peas— a worm in mud finding its way around my roots— or deeply asleep and thus resistant to being read as a morally triumphant being, she buries her mirror The sermon says, "there is no you, so no way for you to fail or fall" In Normandy we bought fish and cake and the children rode the carousel These are the dreams we return to: bread in the sun, oil in the water glass in the foot Blood modifies blood * "Let me be my own fool," sitting on the newspaper perchance in love with an embryonic heart prepared to beat 2.5 billion times, and that's all * Nothing betray us But I love the moment when the boy looks down at a homeless man's shoe and imagines traveling to the center of the earth, hanging on the shoelace like a rope

Copyright © 2010 by Julie Carr. Used by permission of the author.

Because a razor cuts across a frame of film, I wince, squinting my eye, and because my day needs assembly to make sense of the scenes anyway, making a story from some pieces of truth, I go outside to gather those pieces. Thousands of moments spooling out frames of mistakes in my day. As if anyone's to blame, as if anyone could interpret the colliding images, again and again, dragging my imagination behind me, I begin assembling. I don't know anything, so I seek directions, following the path of ants from your palm, out the apartment door to a beach. Is this where I'm supposed to ask if my hands on you bend some light around shade? Maybe I'm not ready for the answer. They say art imitates what we can sculpt or write or just see when we turn ourselves inside out. I can't turn my eye away from the sight of failure. The rain pelts rooftops. I listen to the song, thinking when the sun comes back, beating down the door in my head, I'll salvage whatever sits still long enough for me to render, before anyone knows what really happened.

Copyright © 2010 by A. Van Jordan. Used by permission of the author.

In Africa the wine is cheap, and it is

on St. Mark’s Place too, beneath a white moon.

I’ll go there tomorrow, dark bulk hooded

against what is hurled down at me in my no hat

which is weather: the tall pretty girl in the print dress

under the fur collar of her cloth coat will be standing

by the wire fence where the wild flowers grow not too tall

her eyes will be deep brown and her hair styled 1941 American

will be too; but

I’ll be shattered by then

But now I’m not and can also picture white clouds

impossibly high in blue sky over small boy heartbroken

to be dressed in black knickers, black coat, white shirt,

buster-brown collar, flowing black bow-tie

her hand lightly fallen on his shoulder, faded sunlight falling

across the picture, mother & son, 33 & 7, First Communion Day, 1941—

I’ll go out for a drink with one of my demons tonight

they are dry in Colorado 1980 spring snow.

From Selected Poems by Ted Berrigan, published by Penguin Poets. Copyright © 1994 by Alice Notley, Executrix of the Estate of Ted Berrigan. Reprinted by permission of Alice Notley. All rights reserved.

Take this kiss upon the brow!

And, in parting from you now,

Thus much let me avow:

You are not wrong who deem

That my days have been a dream;

Yet if hope has flown away

In a night, or in a day,

In a vision, or in none,

Is it therefore the less gone?

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

I stand amid the roar

Of a surf-tormented shore,

And I hold within my hand

Grains of the golden sand--

How few! yet how they creep

Through my fingers to the deep,

While I weep--while I weep!

O God! can I not grasp

Them with a tighter clasp?

O God! can I not save

One from the pitiless wave?

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?

This poem is in the public domain.

A hand is not four fingers and a thumb.

Nor is it palm and knuckles,

not ligaments or the fat's yellow pillow,

not tendons, star of the wristbone, meander of veins.

A hand is not the thick thatch of its lines

with their infinite dramas,

nor what it has written,

not on the page,

not on the ecstatic body.

Nor is the hand its meadows of holding, of shaping—

not sponge of rising yeast-bread,

not rotor pin's smoothness,

not ink.

The maple's green hands do not cup

the proliferant rain.

What empties itself falls into the place that is open.

A hand turned upward holds only a single, transparent question.

Unanswerable, humming like bees, it rises, swarms, departs.

—2000

From Given Sugar, Given Salt by Jane Hirshfield, published by HarperCollins. Copyright © 2001 by Jane Hirshfield. Reprinted by permission of the author, all rights reserved.

When Hades decided he loved this girl

he built for her a duplicate of earth,

everything the same, down to the meadow,

but with a bed added.

Everything the same, including sunlight,

because it would be hard on a young girl

to go so quickly from bright light to utter darkness

Gradually, he thought, he'd introduce the night,

first as the shadows of fluttering leaves.

Then moon, then stars. Then no moon, no stars.

Let Persephone get used to it slowly.

In the end, he thought, she'd find it comforting.

A replica of earth

except there was love here.

Doesn't everyone want love?

He waited many years,

building a world, watching

Persephone in the meadow.

Persephone, a smeller, a taster.

If you have one appetite, he thought,

you have them all.

Doesn't everyone want to feel in the night

the beloved body, compass, polestar,

to hear the quiet breathing that says

I am alive, that means also

you are alive, because you hear me,

you are here with me. And when one turns,

the other turns—

That's what he felt, the lord of darkness,

looking at the world he had

constructed for Persephone. It never crossed his mind

that there'd be no more smelling here,

certainly no more eating.

Guilt? Terror? The fear of love?

These things he couldn't imagine;

no lover ever imagines them.

He dreams, he wonders what to call this place.

First he thinks: The New Hell. Then: The Garden.

In the end, he decides to name it

Persephone's Girlhood.

A soft light rising above the level meadow,

behind the bed. He takes her in his arms.

He wants to say I love you, nothing can hurt you

but he thinks

this is a lie, so he says in the end

you're dead, nothing can hurt you

which seems to him

a more promising beginning, more true.

"A Myth of Devotion" from Averno by Louise Glück. Copyright © 2006 by Louise Glück. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

On the day the world ends

A bee circles a clover,

A fisherman mends a glimmering net.

Happy porpoises jump in the sea,

By the rainspout young sparrows are playing

And the snake is gold-skinned as it should always be.

On the day the world ends

Women walk through the fields under their umbrellas,

A drunkard grows sleepy at the edge of a lawn,

Vegetable peddlers shout in the street

And a yellow-sailed boat comes nearer the island,

The voice of a violin lasts in the air

And leads into a starry night.

And those who expected lightning and thunder

Are disappointed.

And those who expected signs and archangels' trumps

Do not believe it is happening now.

As long as the sun and the moon are above,

As long as the bumblebee visits a rose,

As long as rosy infants are born

No one believes it is happening now.

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he's much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

No other end of the world will there be,

No other end of the world will there be.

Warsaw, 1944. Published in The Collected Poems (1988). Copyright © 2006 The Czeslaw Milosz Estate.

To grow old is to lose everything. Aging, everybody knows it. Even when we are young, we glimpse it sometimes, and nod our heads when a grandfather dies. Then we row for years on the midsummer pond, ignorant and content. But a marriage, that began without harm, scatters into debris on the shore, and a friend from school drops cold on a rocky strand. If a new love carries us past middle age, our wife will die at her strongest and most beautiful. New women come and go. All go. The pretty lover who announces that she is temporary is temporary. The bold woman, middle-aged against our old age, sinks under an anxiety she cannot withstand. Another friend of decades estranges himself in words that pollute thirty years. Let us stifle under mud at the pond's edge and affirm that it is fitting and delicious to lose everything.

Reproduced by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. Copyright © 2002 by Donald Hall. All rights reserved.

for the 43 members of Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Local 100, working at the Windows on the World restaurant, who lost their lives in the attack on the World Trade Center

Alabanza. Praise the cook with a shaven head

and a tattoo on his shoulder that said Oye,

a blue-eyed Puerto Rican with people from Fajardo,

the harbor of pirates centuries ago.

Praise the lighthouse in Fajardo, candle

glimmering white to worship the dark saint of the sea.

Alabanza. Praise the cook's yellow Pirates cap

worn in the name of Roberto Clemente, his plane

that flamed into the ocean loaded with cans for Nicaragua,

for all the mouths chewing the ash of earthquakes.

Alabanza. Praise the kitchen radio, dial clicked

even before the dial on the oven, so that music and Spanish

rose before bread. Praise the bread. Alabanza.

Praise Manhattan from a hundred and seven flights up,

like Atlantis glimpsed through the windows of an ancient aquarium.

Praise the great windows where immigrants from the kitchen

could squint and almost see their world, hear the chant of nations:

Ecuador, México, República Dominicana,

Haiti, Yemen, Ghana, Bangladesh.

Alabanza. Praise the kitchen in the morning,

where the gas burned blue on every stove

and exhaust fans fired their diminutive propellers,

hands cracked eggs with quick thumbs

or sliced open cartons to build an altar of cans.

Alabanza. Praise the busboy's music, the chime-chime

of his dishes and silverware in the tub.

Alabanza. Praise the dish-dog, the dishwasher

who worked that morning because another dishwasher

could not stop coughing, or because he needed overtime

to pile the sacks of rice and beans for a family

floating away on some Caribbean island plagued by frogs.

Alabanza. Praise the waitress who heard the radio in the kitchen

and sang to herself about a man gone. Alabanza.

After the thunder wilder than thunder,

after the shudder deep in the glass of the great windows,

after the radio stopped singing like a tree full of terrified frogs,

after night burst the dam of day and flooded the kitchen,

for a time the stoves glowed in darkness like the lighthouse in Fajardo,

like a cook's soul. Soul I say, even if the dead cannot tell us

about the bristles of God's beard because God has no face,

soul I say, to name the smoke-beings flung in constellations

across the night sky of this city and cities to come.

Alabanza I say, even if God has no face.

Alabanza. When the war began, from Manhattan and Kabul

two constellations of smoke rose and drifted to each other,

mingling in icy air, and one said with an Afghan tongue:

Teach me to dance. We have no music here.

And the other said with a Spanish tongue:

I will teach you. Music is all we have.

From Alabanza by Martín Espada. Copyright © 2003 by Martín Espada. Used by permission of W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Forgive me, I’m no good at this. I can’t write back. I never read your letter.

I can’t say I got your note. I haven’t had the strength to open the envelope.

The mail stacks up by the door. Your hand’s illegible. Your postcards were

defaced. Wash your wet hair? Any document you meant to send has yet to

reach me. The untied parcel service never delivered. I regret to say I’m

unable to reply to your unexpressed desires. I didn’t get the book you sent.

By the way, my computer was stolen. Now I’m unable to process words. I

suffer from aphasia. I’ve just returned from Kenya and Korea. Didn’t you

get a card from me yet? What can I tell you? I forgot what I was going to

say. I still can’t find a pen that works and then I broke my pencil. You know

how scarce paper is these days. I admit I haven’t been recycling. I never

have time to read the Times. I’m out of shopping bags to put the old news

in. I didn’t get to the market. I meant to clip the coupons. I haven’t read

the mail yet. I can’t get out the door to work, so I called in sick. I went to

bed with writer’s cramp. If I couldn’t get back to writing, I thought I’d catch

up on my reading. Then Oprah came on with a fabulous author plugging her

best selling book.

Originally published in Santa Monica Review, fall 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Harryette Mullen. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the author.

We, the naturally hopeful,

Need a simple sign

For the myriad ways we're capsized.

We who love precise language

Need a finer way to convey

Disappointment and perplexity.

For speechlessness and all its inflections,

For up-ended expectations,

For every time we're ambushed

By trivial or stupefying irony,

For pure incredulity, we need

The inverted exclamation point.

For the dropped smile, the limp handshake,

For whoever has just unwrapped a dumb gift

Or taken the first sip of a flat beer,

Or felt love or pond ice

Give way underfoot, we deserve it.

We need it for the air pocket, the scratch shot,

The child whose ball doesn't bounce back,

The flat tire at journey's outset,

The odyssey that ends up in Weehawken.

But mainly because I need it—here and now

As I sit outside the Caffe Reggio

Staring at my espresso and cannoli

After this middle-aged couple

Came strolling by and he suddenly

Veered and sneezed all over my table

And she said to him, "See, that's why

I don't like to eat outside."

Reprinted from Overnight by Paul Violi. Copyright © 2007 by Paul Violi. Used by permission of Hanging Loose Press.

The green catalpa tree has turned All white; the cherry blooms once more. In one whole year I haven't learned A blessed thing they pay you for. The blossoms snow down in my hair; The trees and I will soon be bare. The trees have more than I to spare. The sleek, expensive girls I teach, Younger and pinker every year, Bloom gradually out of reach. The pear tree lets its petals drop Like dandruff on a tabletop. The girls have grown so young by now I have to nudge myself to stare. This year they smile and mind me how My teeth are falling with my hair. In thirty years I may not get Younger, shrewder, or out of debt. The tenth time, just a year ago, I made myself a little list Of all the things I'd ought to know, Then told my parents, analyst, And everyone who's trusted me I'd be substantial, presently. I haven't read one book about A book or memorized one plot. Or found a mind I did not doubt. I learned one date. And then forgot. And one by one the solid scholars Get the degrees, the jobs, the dollars. And smile above their starchy collars. I taught my classes Whitehead's notions; One lovely girl, a song of Mahler's. Lacking a source-book or promotions, I showed one child the colors of A luna moth and how to love. I taught myself to name my name, To bark back, loosen love and crying; To ease my woman so she came, To ease an old man who was dying. I have not learned how often I Can win, can love, but choose to die. I have not learned there is a lie Love shall be blonder, slimmer, younger; That my equivocating eye Loves only by my body's hunger; That I have forces true to feel, Or that the lovely world is real. While scholars speak authority And wear their ulcers on their sleeves, My eyes in spectacles shall see These trees procure and spend their leaves. There is a value underneath The gold and silver in my teeth. Though trees turn bare and girls turn wives, We shall afford our costly seasons; There is a gentleness survives That will outspeak and has its reasons. There is a loveliness exists, Preserves us, not for specialists.

From Heart's Needle by W. D. Snodgrass, published by Alfred A. Knopf. Copyright © 1957, 1959 by W. D. Snodgrass. Used with permission.

As I walked out one evening,

Walking down Bristol Street,

The crowds upon the pavement

Were fields of harvest wheat.

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway:

‘Love has no ending.

‘I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you

Till China and Africa meet,

And the river jumps over the mountain

And the salmon sing in the street,

‘I’ll love you till the ocean

Is folded and hung up to dry

And the seven stars go squawking

Like geese about the sky.

‘The years shall run like rabbits,

For in my arms I hold

The Flower of the Ages,

And the first love of the world.’

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

‘O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.

‘In the burrows of the Nightmare

Where Justice naked is,

Time watches from the shadow

And coughs when you would kiss.

‘In headaches and in worry

Vaguely life leaks away,

And Time will have his fancy

To-morrow or to-day.

‘Into many a green valley

Drifts the appalling snow;

Time breaks the threaded dances

And the diver’s brilliant bow.

‘O plunge your hands in water,

Plunge them in up to the wrist;

Stare, stare in the basin

And wonder what you’ve missed.

‘The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea-cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead.

‘Where the beggars raffle the banknotes

And the Giant is enchanting to Jack,

And the Lily-white Boy is a Roarer,

And Jill goes down on her back.

‘O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.

‘O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.’

It was late, late in the evening,

The lovers they were gone;

The clocks had ceased their chiming,

And the deep river ran on.

From Another Time by W. H. Auden, published by Random House. Copyright © 1940 W. H. Auden, renewed by the Estate of W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

I should have thought in a dream you would have brought some lovely, perilous thing, orchids piled in a great sheath, as who would say (in a dream), "I send you this, who left the blue veins of your throat unkissed." Why was it that your hands (that never took mine), your hands that I could see drift over the orchid-heads so carefully, your hands, so fragile, sure to lift so gently, the fragile flower-stuff-- ah, ah, how was it You never sent (in a dream) the very form, the very scent, not heavy, not sensuous, but perilous--perilous-- of orchids, piled in a great sheath, and folded underneath on a bright scroll, some word: "Flower sent to flower; for white hands, the lesser white, less lovely of flower-leaf," or "Lover to lover, no kiss, no touch, but forever and ever this."

Copyright © 1982 by the Estate of Hilda Doolittle. Used with permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this poem may be reproduced in any form without the written consent of the publisher.

1 People think, at the theatre, an audience is tricked into believing it's looking at life. The film image is so large, it goes straight into your head. There's no room to be aware of or interested in people around you. Girls and cool devices draw audience, but unraveling the life of a real human brings the outsiders. I wrote before production began, "I want to include all of myself, a heartbroken person who hasn't worked for years, who's simply not dead." Many fans feel robbed and ask, "What kind of show's about one person's unresolved soul?" 2 There's sympathy for suffering, also artificiality. Having limbs blown off is some person's reality, not mine. I didn't want to use sympathy for others as a way through my problems. There's a gap between an audience and particulars, but you can be satisfied by particulars, on several levels: social commentary, sleazy fantasy. Where my film runs into another's real life conditions seem problematic, but they don't link with me. The linking is the flow of images, thwarting a fan's transference. If you have empathy to place yourself in my real situation of face-to-face intensity, then there would be no mirror, not as here. 3 My story is about the human race in conflict with itself and nature. An empathic princess negotiates peace between nations and huge creatures in the wild. I grapple with the theme, again and again. Impatience and frustration build among fans. "She achieves a personal voice almost autistic in lack of affect, making ambiguous her well-known power to communicate emotion, yet accusing a system that mistakes what she says." Sex, tech are portrayed with lightness, a lack of divisions that causes anxieties elsewhere. When I find a gap, I don't fix it, don't intrude like a violent, stray dog, separating flow and context, to conform what I say to what you see. Time before the show was fabulous, blank. When I return, as to an object in space, my experience is sweeter, not because of memory. The screen is a mirror where a butterfly tries so hard not to lose the sequence of the last moments. I thought my work should reflect society, like mirrors in a cafe, double-space. There's limited time, but we feel through film media we've more. 4 When society deterritorialized our world with money, we managed our depressions via many deterritorializations. Feeling became vague, with impersonal, spectacular equivalents in film. My animator draws beautifully, but can't read or write. He has fears, which might become reality, but Godzilla is reality. When I saw the real princess, I found her face inauspicious, ill-favored, but since I'd heard she was lovely, I said, "Maybe, she's not photogenic today." Compared to my boredom, I wondered if her life were not like looking into a stream at a stone, while water rushed over me. I told her to look at me, so her looking is what everything rushes around. I don't care about story so much as, what do you think of her? Do you like her? She's not representative, because of gaps in the emotion, only yummy parts, and dialogue that repeats. She pencils a black line down the back of her leg. A gesture turns transparent and proliferates into thousands of us doing the same. Acknowledging the potential of a fan club, she jokingly describes it as "suspect". She means performance comes out through the noise. 5 At the bar, you see a man catch hold of a girl by the hair and kick her. You could understand both points of view, but in reality, no. You intervene, feeling shame for hoping someone else will. It becomes an atmosphere, a situation, by which I mean, groups. In school we're taught the world is round, and with our own eyes we confirmed a small part of what we could imagine. Because you're sitting in a dark place, and I'm illuminated, and a lot of eyes are directed at me, I can be seen more clearly than if I mingled with you, as when we were in high school. We were young girls wanting to describe love and to look at it from outer space.

From Nest by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge. Copyright © 2003 by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Kelsey St. Press. Special thanks to Conjunctions where the poem first appeared. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

(after the spanish) forgive me if i laugh you are so sure of love you are so young and i too old to learn of love. the rain exploding in the air is love the grass excreting her green wax is love and stones remembering past steps is love, but you. you are too young for love and i too old. once. what does it matter when or who, i knew of love. i fixed my body under his and went to sleep in love all trace of me was wiped away forgive me if i smile young heiress of a naked dream you are so young and i too old to learn of love.

From Homegirls & Handgrenades by Sonia Sanchez. Copyright © 2007 by Sonia Sanchez. Reprinted by permission of White Pine Press.

(at St. Mary’s)

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

From Quilting: Poems 1987–1990 by Lucille Clifton. Copyright © 2001 by Lucille Clifton. Reprinted with permission of BOA Editions Ltd. All rights reserved.

It was first dark when the plow turned it up.

Unsown, it came fleshless, mud-ruddled, nothing

but itself, the tendon's bored eye threading

a ponderous needle. And yet the pocked fist

of one end dared what was undone

in the strewing, defied the mouth of the hound

that dropped it.

The whippoorwill began

again its dusk-borne mourning. I had never

seen what urgent wing disembodied

the voice, would fail to recognize its broken

shell or shadow or its feathers strewn

before me. As if afraid of forgetting,

it repeated itself, mindlessly certain.

Here.

I threw the bone toward that incessant claiming,

and watched it turned by rote, end over end over end.

From Pinion: An Elegy by Claudia Emerson. Copyright © 2002 by Claudia Emerson. Reproduced with the permission of Louisiana State University Press. All rights reserved.

Descartes in Love

Love, accepting that we are not pure and lucent hearts, ricocheting towards each other like unlatched stars—no, we are tainted with self. We sometimes believe the self is an invisible glass, just as we believe the body is a suit made of meat. Doubt all things invisible. Doubt all things visible.

Colin Powell

Not to be a tragic person. What is a tragic person? The victim of a crime who does not realize the criminal is himself.

Adonis Prettyboy in Hell And then her son with love-gun and a quiver snatched a love-shaft and delivered—a twiggy arrow in her nipple like a nasty sliver... A big pig stuck me with his tusk, but it's life that's the bore, silly! I never got desire, I always got what I wanted And in this hallway incredulous of lights, I want wild pears, firm booblike fruit—Daffodils! Clovers! And the trill of starlings why not! We could grow apples here... Apples? So, I suppose I do miss her —You know when I fell out of life I grabbed her heart like a rope;

Virginia Woolf

The target audience of my secrets is not my friends, but my journals and the strangers who will read them in the future.

Child of Immigrants

I used to pretend I was American.

This was until I realized I was American.

Richard Rorty

What is forgiveness? When someone else's sin becomes merely an action we ourselves might plausibly commit. The virtue of hypocrisy—we temporarily become people other than ourselves and can notice our actions from the other side, as saintly as no one.

Io Symbol is abridgement. I am not a cow and Argus not omniscience. We are clockfraught beings. The man I love stopped my heart when he froze the world to night. My heart being part of the world.

Copyright © 2011 by Ken Chen. Used with permission of the author.

Music: Sexual misery is wearing you out.

Music: Known as the Philosopher’s Stair for the world-weariness which climbing it inspires. One gets nowhere with it.

Paris: St-Sulpice in shrouds.

Paris: You’re falling into disrepair, Eiffel Tower this means you! Swathed in gold paint, Enguerrand Quarton whispering come with me under the shadow of this gold leaf.

Music: The unless of a certain series.

Mathematics: Everyone rolling dice and flinging Fibonacci, going to the opera, counting everything.

Fire: The number between four and five.

Gold leaf: Wedding dress of the verb to have,it reminds you of of.

Music: As the sleep of the just. We pass into it and out again without seeming to move. The false motion of the wave, “frei aber einsam.”

Steve Evans: I saw your skull! It was between your thought and your face.

Melisse: How I saw her naked in Brooklyn but was not in Brooklyn at the time.

Art: That’s the problem with art.

Paris: I was in Paris at the time! St-Sulpice in shrouds “like Katharine Hepburn.”

Katharine Hepburn: Oh America! But then, writing from Paris in the thirties, it was to you Benjamin compared Adorno’s wife. Ghost citizens of the century, sexual misery is wearing you out.

Misreading: You are entering the City of Praise, population two million three hundred thousand . . .

Hausmann’s Paris: The daughter of Midas in the moment just after. The first silence of the century then the king weeping.

Music: As something to be inside of, as inside thinking one feels thought of, fly in the ointment of the mind!

Sign at Jardin des Plantes: games are forbidden in the labyrinth .

Paris: Museum city, gold lettering the windows of the wedding-dress shops in the Jewish Quarter. “Nothing has been changed,” sez Michael, “except for the removal of twenty-seven thousand Jews.”

Paris 1968: The antimuseum museum.

The Institute for Temporary Design: Scaffolding, traffic jam, barricade, police car on fire, flies in the ointment of the city.

Gilles Ivain: In your tiny room behind the clock, your bent sleep, your Mythomania.

Gilles Ivain: Our hero, our Anti-Hausmann.

To say about Flemish painting: “Money-colored light.”

Music: “Boys on the Radio.”

Boys of the Marais: In your leather pants and sexual pose, arcaded shadows of the Place des Vosges.

Mathematics: And all that motion you supposed was drift, courtyard with the grotesque head of Apollinaire, Norma on the bridge, proved nothing but a triangle fixed by the museum and the opera and St-Sulpice in shrouds.

The Louvre: A couple necking in an alcove, in their brief bodies entwined near the Super-Radiance Hall visible as speech.

Speech: The bird that bursts from the mouth shall not return.

Pop song: We got your pretty girls they’re talking on mobile phones la la la.

Enguerrand Quarton: In your dream gold leaf was the sun, salve on the kingdom of the visible.

Gold leaf: The mind makes itself a Midas, it cannot hold and not have.

Thus: I came to the city of possession.

Sleeping: Behind the clock, in the diagon, in your endless summer night, in the city remaking itself like a wave in which people live or are said to live, it comes down to the same thing, an exaggerated sense of things getting done.

Paris: The train station’s a museum, opera in the place of the prison.

Later: The music lacquered with listen.

Courtesy of University of California Press.

I stared at the ruin, the powder of the dead

now beneath ground, a crowd

assembled and breathing with

indiscernible sadnesses, light

from other light, far off

and without explanation. Somewhere unseen

the ocean deepened then and now

into more ocean, the black fins

of the bony fish obscuring

its bottommost floor, carcasses of mollusks

settling, casting one last blur of sand,

unable to close again. Next to me a woman,

the seventeen pins it took to set

her limb, to keep every part flush with blood.

*

In the book on the ancient mayfly

which lives only four hundred minutes

and is, for this reason, called ephemeral,

I couldn't understand why the veins laid across

the transparent sheets of wings, impossibly

fragile, weren't blown through in their half-day

of flight. Or how that design has carried the species

through antiquity with collapsing

horses, hailstorms and diffracted confusions of light.

*

If I remember correctly what's missing

broke off all at once, not into streets

but into rows portioned off for shade as it

fell here, the sun there

where the poled awning ended. Didn't the heat

and dust funnel down

to the condemned as they fought

until the animal took them completely? Didn't at least one stand

perfectly still?

*

I said to myself: Beyond my husband there are strange trees

growing on one of the seven hills.

They look like intricately tended bonsais, but

enormous and with unreachable hollows.

He takes photographs for our black folios,

thin India paper separating one from another.

There is no scientific evidence of consciousness

lasting outside the body. I think when I die

it will be completely.

*

But it didn't break off all at once.

It turns out there is a fault line under Rome

that shook the theater walls

slight quake by quake. After the empire fell

the arena was left untended

and exotic plants spread a massive overgrowth,

their seeds brought from Asia and Africa, sewn accidentally

in the waste of the beasts.

Like our emptying, then aching questions,

the vessel filled with unrecognizable faunas.

*

How great is the darkness in which we grope,

William James said, not speaking of the earth, but the mind

split into its caves and plinth from which to watch

its one great fight.

And then, when it is over,

when those who populate your life return

to their curtained rooms and lie down without you,

you are alone, you

are quarry.

*

When the mayflies emerge it is in great numbers

from lakes where they have lived in nymphal skins

through many molts. At the last

a downy skin is shed and what proofed them

is gone. Above water there is

nothing for them to feed on—

they don't even look, except for each other.

They form hurried swarms in that starving, sudden hour

and mate fully. When it is finished it is said

the expiring flies gather beneath boatlights

or lampposts and die under them minutely,

drifting down in a flock called snowfall.

*

Nothing wants to break, but this wanted to break,

built for slaughter, open arches to climb through,

lines of glassless squares above, elaborate

pulleys raising the animals on platforms

out of the passaged darkness.

When one is the site of so much pain, one must pray

to be abandoned. When abandonment is

that much more—beauty and terror

before every witness and suddenly

you are not there.

Copyright © 2008 by Katie Ford. Reprinted from Colosseum with the permission of Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

I believe there is something else

entirely going on but no single

person can ever know it,

so we fall in love.

It could also be true that what we use

everyday to open cans was something

much nobler, that we'll never recognize.

I believe the woman sleeping beside me

doesn't care about what's going on

outside, and her body is warm

with trust

which is a great beginning.

Copyright © 2001 by Matthew Rohrer. From Satellite. Reprinted with permission of Verse Press.

A point, a line, alignment. Lovely

the lingering lights along the shore

as the century lays itself out for observation:

hunger and the youthful indiscretion.

I am one of many, or not even one,

but am of many one who watches the waves

and allows the particulate sand its say,

say, its sound, susurrant. Of many one

engaging the ear as if the Pacific

meant its name, as if the edge of

continent contented us with boundary.

Draw a line from A to B. Live there.

Copyright © 2012 by Bin Ramke. Used with permission of the author.

Often now as an old man Who sleeps only four hours a night, I wake before dawn, dress and go down To my study to start typing: Poems, letters, more pages In the book of recollections. Anything to get words flowing, To get them out of my head Where they’re pressing so hard For release it’s like a kind Of pain. My study window Faces east, out over the meadow, And I see this morning That the sheep have scattered On the hillside, their white shapes Making the pattern of the stars In Canis Major, the constellation Around Sirius, the Dog Star, Whom my father used to point Out to us, calling it For some reason I forget Little Dog Peppermint. What is this line I’m writing? I never could scan in school. It’s certainly not an Alcaic. Nor a Sapphic. Perhaps it’s The short line Rexroth used In The Dragon & The Unicorn, Tossed to me from wherever He is by the Cranky Old Bear (but I loved him). It’s really Just a prose cadence, broken As I breathe while putting My thoughts into words; Mostly they are stored-up Memories—dove sta memoria. Which one of the Italians Wrote that? Dante or Cavalcanti? Five years ago I’d have had The name on the tip of my tongue But no longer. In India They call a storeroom a godown, But there’s inventory For my godown. I can’t keep Track of what’s in there. All those people in books From Krishna & the characters In the Greek Anthology Up to the latest nonsense Of the Deconstructionists, Floating around in my brain, A sort of “continuous present” As Gertrude Stein called it; The world in my head Confusing me about the messy World I have to live in. Better the drunken gods of Greece Than a life ordained by computers. My worktable faces east; I watch for the coming Of the dawnlight, raising My eyes occasionally from The typing to rest them, There is always a little ritual, A moment’s supplication To Apollo, god of the lyre; Asking he keep an eye on me That I commit no great stupidity. Phoebus Apollo, called also Smintheus the mousekiller For the protection he gives The grain of the farmers. My Dawns don't come up like thunder Though I have been to Mandalay That year when I worked in Burma. Those gentle, tender people Puzzled by modern life; The men, the warriors, were lazy, It was the women who hustled, Matriarchs running the businesses. And the girls bound their chests So their breasts wouldn’t grow; Who started that, and why? My dawns come up circumspectly, Quietly with no great fuss. Night was and in ten minutes Day is, unless of course It’s raining hard. Then comes My first breakfast. I can’t cook So it’s only tea, puffed wheat and Pepperidge Farm biscuits. Then a cigar. Dr Luchs Warned me the cigars Would kill me years ago But I’m still here today.

Copyright © 2005 by James Laughlin. From Byways. Reprinted with permission of New Directions Publishing.

Days of nothingness

Days of clear skies the temperature descending

Days of no telephone calls or all the wrong ones

Days of complete boredom and nothing

is happening

Days of 1967 coming to a close in the frigid condition of chest

cold and cough

drops

Days of afternoons in the life of a young girl

not being on time

Days of daydreams exploding

Days of utter frustration

Days of my film being cursed and myself

with the curse never lifting

Days of closed windows to keep the cold

out the livingroom warm

Days of avoiding lunch for a phone-call

with change of plans for the day

Days of posting letters

Days of no mail today

Days of fatigue and amphetamine highs

Days of Charles Edward Ives

Days of the 4:00 pm doldrums

Days of wonder drugs to challenge the common cold

Days of utter frustration

Days of forgetting

From No Respect: New & Selected Poems 1964-2000 by Gerard Malanga. Copyright © 2001 by Gerard Malanga. Reprinted with the permission of Black Sparrow Press. All rights reserved.

Sonya's so good that all the guys

pick on her, so the evening's narrative goes. I've heard she wears

yellow t-shirts each time to match her hair. Last time her tennis

shoes got so dusty that she had to throw them out because there

was no way on earth that they could be white again.

Trunks shrink like deflated accor-

dions, like melodramatic arguments after they've met face to

face with someone's indifference. A baby cries and pouts

while her mother is trying to scoop more Velveta on to her

nacho. The father is strung out on something, someone in

back of us says. A teenager with severe acne turns around

and fires a dart full of cavities into my gaze. We give in to the

pleasure of destruction for the sheer sake of waste. What

inside, the collision, the jerk on the nape that makes the

driver wonder whether this one's it. Swallow me dust while

the crowd cheers and claps its French fries away into the

space between a nearby neon and the floodlights gathering

an army of many sized moths.

Reprinted from American Poet, Fall 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Mónica de la Torre. Reprinted by permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

From The Poems of Dylan Thomas, published by New Directions. Copyright © 1952, 1953 Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1937, 1945, 1955, 1962, 1966, 1967 the Trustees for the Copyrights of Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1938, 1939, 1943, 1946, 1971 New Directions Publishing Corp. Used with permission.

Huffy Henry hid the day,

unappeasable Henry sulked.

I see his point,—a trying to put things over.

It was the thought that they thought

they could do it made Henry wicked & away.

But he should have come out and talked.

All the world like a woolen lover

once did seem on Henry's side.

Then came a departure.

Thereafter nothing fell out as it might or ought.

I don't see how Henry, pried

open for all the world to see, survived.

What he has now to say is a long

wonder the world can bear & be.

Once in a sycamore I was glad

all at the top, and I sang.

Hard on the land wears the strong sea

and empty grows every bed.

From The Dream Songs by John Berryman, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Copyright © 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969 by John Berryman. Used with permission.

There sat down, once, a thing on Henry's heart só heavy, if he had a hundred years & more, & weeping, sleepless, in all them time Henry could not make good. Starts again always in Henry's ears the little cough somewhere, an odour, a chime. And there is another thing he has in mind like a grave Sienese face a thousand years would fail to blur the still profiled reproach of. Ghastly, with open eyes, he attends, blind. All the bells say: too late. This is not for tears; thinking. But never did Henry, as he thought he did, end anyone and hacks her body up and hide the pieces, where they may be found. He knows: he went over everyone, & nobody's missing. Often he reckons, in the dawn, them up. Nobody is ever missing.

From The Dream Songs by John Berryman, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Copyright © 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969 by John Berryman. Used with permission.

Filling her compact & delicious body with chicken páprika, she glanced at me twice. Fainting with interest, I hungered back and only the fact of her husband & four other people kept me from springing on her or falling at her little feet and crying 'You are the hottest one for years of night Henry's dazed eyes have enjoyed, Brilliance.' I advanced upon (despairing) my spumoni.—Sir Bones: is stuffed, de world, wif feeding girls. —Black hair, complexion Latin, jewelled eyes downcast . . . The slob beside her feasts . . . What wonders is she sitting on, over there? The restaurant buzzes. She might as well be on Mars. Where did it all go wrong? There ought to be a law against Henry. —Mr. Bones: there is.

From The Dream Songs by John Berryman, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Copyright © 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969 by John Berryman. Used with permission.

I. Before Breakfast When the sun turns gray and I become tired of looking at your many-colored shoes I will give you balloons for all the holes we speak too much to fill. Who believes in air, nowadays? Or do you prefer tea with the dried fruit I will have to throw out the window of your room? Because I want this to stop I want this to stop I want this II. Towards Moorish Spain To kill the dragons is a different thing in my family there are only lizards. In Sevilla--never famous for its lamps-- a dissected crocodile hangs from a roof. The reptile, the Crown’s Byzantine gift. Its teeth suspended in the air of the cathedral. I stole a pair of shoes; but didn’t run far from the orchard where water had women’s scent. Thirst is not fear, thirst is not green, but has wings like dragons, or airplanes. As oranges in Sevilla, driven by a strange desire to stay where they are. Floating. Suspended. III. Towards Virgo The Milky Way is not only expanding; the Bang is not only a Bang. It is drifting and being pulled away from, let’s say, something. Because dark matter is ninety nine of what there is and visible matter is so small it clusters together and forms a Great Wall. China and Spain and my eyes reading the paper. We are still together, are we not, wondering if.

Poem previously published in Fence magazine. Reprinted by permission.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime...

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

This poem is in the public domain.

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman's days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute to minute they live;

The stone's in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven's part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

This poem is in the public domain.

INSERT SHOT: Einstein’s notebook 1905—DAY 1: a theory that is based on two postulates (a) that the speed of light in all inertial frames is constant, independent of the source or observer. As in, the speed of light emitted from the truth is the same as that of a lie coming from the lamp of a face aglow with trust, and (b) the laws of physics are not changed in all inertial systems, which leads to the equivalence of mass and energy and of change in mass, dimension, and time; with increased velocity, space is compressed in the direction of the motion and time slows down. As when I look at Mileva, it’s as if I’ve been in a space ship traveling as close to the speed of light as possible, and when I return, years later, I’m younger than when I began the journey, but she’s grown older, less patient. Even a small amount of mass can be converted into enormous amounts of energy: I’ll whisper her name in her ear, and the blood flows like a mallet running across vibes. But another woman shoots me a flirting glance, and what was inseparable is now cleaved in two.

"Einstein Defining Special Relativity", from Quantum Lyrics by A. Van Jordan. Copyright © 2007 by A. Van Jordan. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Sometimes she's Confucian-- resolute in privation. . . . Each day, more immobile, hip not mending, legs swollen; still she carries her grief with a hard steadiness. Twelve years uncompanioned, there's no point longing for what can't return. This morning, she tells me, she found a robin hunched in the damp dirt by the blossoming white azalea. Still there at noon-- she went out in the yard with her 4-pronged metal cane-- it appeared to be dying. Tonight, when she looked again, the bird had disappeared and in its place, under the bush, was a tiny egg-- "Beautiful robin's-egg blue"-- she carried carefully indoors. "Are you keeping it warm?" I ask--what am I thinking?-- And she: "Gail, I don't want a bird, I want a blue egg."

From They Can't Take That Away from Me by Gail Mazur. Copyright © 2000 by Gail Mazur. Reprinted with permission by The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

It’s the same when love comes to an end,

or the marriage fails and people say

they knew it was a mistake, that everybody

said it would never work. That she was

old enough to know better. But anything

worth doing is worth doing badly.

Like being there by that summer ocean

on the other side of the island while

love was fading out of her, the stars

burning so extravagantly those nights that

anyone could tell you they would never last.

Every morning she was asleep in my bed

like a visitation, the gentleness in her

like antelope standing in the dawn mist.

Each afternoon I watched her coming back

through the hot stony field after swimming,

the sea light behind her and the huge sky

on the other side of that. Listened to her

while we ate lunch. How can they say

the marriage failed? Like the people who

came back from Provence (when it was Provence)

and said it was pretty but the food was greasy.

I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

but just coming to the end of his triumph.

Copyright © 2005 Jack Gilbert. From Refusing Heaven, 2005, Alfred A. Knopf. Reprinted with permission.

Among the first we learn is good-bye,

your tiny wrist between Dad's forefinger

and thumb forced to wave bye-bye to Mom,

whose hand sails brightly behind a windshield.

Then it's done to make us follow:

in a crowded mall, a woman waves, "Bye,

we're leaving," and her son stands firm

sobbing, until at last he runs after her,

among shoppers drifting like sharks

who must drag their great hulks

underwater, even in sleep, or drown.

Living, we cover vast territories;

imagine your life drawn on a map—

a scribble on the town where you grew up,

each bus trip traced between school

and home, or a clean line across the sea

to a place you flew once. Think of the time

and things we accumulate, all the while growing

more conscious of losing and leaving. Aging,

our bodies collect wrinkles and scars

for each place the world would not give

under our weight. Our thoughts get laced

with strange aches, sweet as the final chord

that hangs in a guitar's blond torso.

Think how a particular ridge of hills

from a summer of your childhood grows

in significance, or one hour of light--

late afternoon, say, when thick sun flings

the shadow of Virginia creeper vines

across the wall of a tiny, white room

where a girl makes love for the first time.

Its leaves tremble like small hands

against the screen while she weeps

in the arms of her bewildered lover.

She's too young to see that as we gather

losses, we may also grow in love;

as in passion, the body shudders

and clutches what it must release.

From Eve's Striptease by Julia Kasdorf. Copyright © 1998 by Julia Kasdorf. All rights are controlled by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA 15261. Used by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved.

—to Dan Maddening shadow across your line of vision— what might be there, then isn't, making it hard to be on the lookout, concentrate, even hear—well, enough of the story I've given you, at least—you've had your fill, never asked for this, though you were the one to put a hand out, catch hold, not about to let me vanish the way of the two you lost already to grief's lure. I'm here; close your eyes, listen to our daughter practicing, going over and over the Bach, getting the mordents right, to make the lovely Invention definite. What does mordent mean, her piano teacher asked—I was waiting in the kitchen and overheard—I don't know, something about dying? No; morire means to die, mordere means to take a bite out of something—good mistake, she said. Not to die, to take a bite—what you asked of me—and then pleasure in the taking. Close your eyes now, listen. No one is leaving.

From Bad River Road by Debra Nystrom. Copyright © 2009 by Debra Nystrom. Used by permission of Sarabande Books, Inc. All rights reserved.

Reanimated, spirit restored, reincorporated, body restored, I contemplate between dreams the scene I’ve stolen like the one who took fire, like the one who opened the devil box out of curiosity, like the one who saw her equal and her life’s love were the same and so effortlessly brought them together. I took exactly what was not mine, with my eyes. I saw the sea inside you: on your surface, mud. I kissed you like a shipwreck, like one who insufflates the word. With my lips I traveled that entire continent, Adam, from dirt, Nothing. I knew myself in your substance, grounded there, emitting aromatic fumes, an amatory banquet of ashes.

Copyright © 2002 by Pura López-Colomé. Reprinted from No Shelter, with the permission of Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota. All rights reserved.

after information received in The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 4 v 86

The population center of the USA Has shifted to Potosi, in Missouri. The calculation employed by authorities In arriving at this dislocation assumes That the country is a geometric plane, Perfectly flat, and that every citizen, Including those in Alaska and Hawaii And the District of Columbia, weighs the same; So that, given these simple presuppositions, The entire bulk and spread of all the people Should theoretically balance on the point Of a needle under Potosi in Missouri Where no one is residing nowadays But the watchman over an abandoned mine Whence the company got the lead out and left. "It gets pretty lonely here," he says, "at night."