Dedicated to the Poet Agostinho Neto,

President of The People’s Republic of Angola: 1976

1

I will no longer lightly walk behind

a one of you who fear me:

Be afraid.

I plan to give you reasons for your jumpy fits

and facial tics

I will not walk politely on the pavements anymore

and this is dedicated in particular

to those who hear my footsteps

or the insubstantial rattling of my grocery

cart

then turn around

see me

and hurry on

away from this impressive terror I must be:

I plan to blossom bloody on an afternoon

surrounded by my comrades singing

terrible revenge in merciless

accelerating

rhythms

But

I have watched a blind man studying his face.

I have set the table in the evening and sat down

to eat the news.

Regularly

I have gone to sleep.

There is no one to forgive me.

The dead do not give a damn.

I live like a lover

who drops her dime into the phone

just as the subway shakes into the station

wasting her message

canceling the question of her call:

fulminating or forgetful but late

and always after the fact that could save or

condemn me

I must become the action of my fate.

2

How many of my brothers and my sisters

will they kill

before I teach myself

retaliation?

Shall we pick a number?

South Africa for instance:

do we agree that more than ten thousand

in less than a year but that less than

five thousand slaughtered in more than six

months will

WHAT IS THE MATTER WITH ME?

I must become a menace to my enemies.

3

And if I

if I ever let you slide

who should be extirpated from my universe

who should be cauterized from earth

completely

(lawandorder jerkoffs of the first the

terrorist degree)

then let my body fail my soul

in its bedeviled lecheries

And if I

if I ever let love go

because the hatred and the whisperings

become a phantom dictate I o-

bey in lieu of impulse and realities

(the blossoming flamingos of my

wild mimosa trees)

then let love freeze me

out.

I must become

I must become a menace to my enemies.

Copyright © 2017 by the June M. Jordan Literary Estate. Used with the permission of the June M. Jordan Literary Estate, www.junejordan.com.

For Howard Zinn

who will come to tell us what we know

that the king’s clothes are soiled with

the history of our blood and sweat

who memorializes us when we have been vanquished

who recounts our moments of resistance, explicates

our struggles, sings of our sacrifices to those

unable to hear our song

who speaks of our triumphs, of how we

altered the course of a raging river of oppression

how we turned our love for each other into a

garrison of righteous rebellion

who shows us even in failure, when we

have been less than large, when our own

prejudices have been turned against us like

stolen weapons

who walks among us, willing to tell the truth

about the monster of lies, an eclipse that casts

a shadow dark enough to cover centuries

what manner of man, of woman, of truth teller

roots around the muck of history, the word covered

in the mud of denial, the mythology of the conquerors

let them be Zinn, let them sing to the people of history

let their song come slowly, on the periphery of canon

of history departments owned by corporate prevaricators

let their song be sung in small circles, furtive meetings

lonely readers, underground and under siege

their song, the seed crushed to earth, and growing

now a tree, with fruit, multiplying truth.

Copyright © 2014 by Kenneth Carroll. Reprinted from Split This Rock’s The Quarry: A Social Justice Poetry Database.

If we must die—let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die—oh, let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

Oh, Kinsmen! We must meet the common foe;

Though far outnumbered, let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one deathblow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we'll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Used by permission of the Archives of Claude McKay (Carl Cowl, administrator).

for my ancestor

in the Pennsylvania 25th Colored Infantry

aboard the Suwanee

First a penny-sized hole in the hull

then eager saltwater rushing over

us and clouds swirling and clotting

the moonlight—no time to stop and look upon it

as the hole becomes an iron mouth,

makes strange sounds, peels and tears

open iron as iron should not open—

muffled and heavy us becoming underwater

we confused the metal echo and thunder

as the same death knell from God’s mouth—

we been done floated all this way down

in dark blue used

uniforms, how far from slavers’ dried-out fields

in Virginia, Pennsylvania—wherever

we came from now we

barely and only

see and hear an ocean

whipped into storm

not horror, not glory, but storm

not fear, not power, but focus

on the work of breathing, living as the storm

rocks us and our insides upside down turns

hard tack into empty nausea—

so close to death I thought I saw the blaze-

sick fields of Berryville again, the curling fingers

of tobacco, hurt fruit and flower—

but no, but no.

I say no to death now. I’m nobody’s slave

now. I’m alive and not alone,

one of those who escaped and made myself

a soldier a weapon a stone in David’s sling

riding the air above the deep. I grow more dangerous

to those who want me. I ain’t going back

to anywhere I been before.

I grab a bucket. You grab a bucket. We the 25th

Pennsylvania Colored Infantry, newly formed

and too alive and close to free

to sink below this midnight water. 36 hours—chaos

shoveling-lifting-throwing ocean back into ocean

to reach land and war in the Carolinas.

I stole my body back from death and going down

more than once. I steal my breath

tonight and every night I will not drown.

Copyright © 2020 by Aaron Coleman. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on March 24, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Go live with yourself after what you didn’t do.

Go and be left behind. Pre-package

your defense, tell yourself

you were doing

your oath, guarding the futility of

your corrupted good,

discerning the currency of some.

As if them over all else.

Over us.

Above God and Spirit.

You over me, you think.

This is no shelter in justice not sheltering with

enclosure of soft iron a sheltering of injustices

into an inferno flooding of your crimes committed

and sheltered by most culprit of them all.

These nesting days come

outward springs of truth,

dismantle the old structures,

their impulse for colony—I am done

with it, the likes of you.

To perpetrate.

To perpetrate lack of closure, smolders of unrest.

To perpetrate long days alone, centuries gone deprived.

To be complicit in adding to the

perpetration of power on a neck,

there and shamed,

court of ancestors to disgrace

you, seeing and to have done nothing.

Think you can be like them.

Work like them.

Talk like them.

Never truly to be accepted,

always a pawn.

Copyright © 2020 by Mai Der Vang. Originally published with the Shelter in Poems initiative on poets.org.

When the pickup truck, with its side mirror,

almost took out my arm, the driver’s grin

reflected back; it was just a horror

show that was never going to happen,

don’t protest, don’t bother with the police

for my benefit, he gave me a smile—

he too was startled, redness in his face—

when I thought I was going, a short while,

to get myself killed: it wasn’t anger

when he bared his teeth, as if to caution

calm down, all good, no one died, ni[ght, neighbor]—

no sense getting all pissed, the commotion

of the past is the past; I was so dim,

he never saw me—of course, I saw him.

Copyright © 2020 by Tommye Blount. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on February 19, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Maggot & Mosquito mother infectious

encounters. Call home to the fen. Flooding

makes a marsh and unhouses the land.

I picture skin, inch by inch conversion

to new flesh. Without medicine i’ve seen the body

be made a speedy disposal. Dejected ground.

Profitable & prosper both contain pro.

Prospero Prospero Prospero.

I too have made incantation

of the man’s name

who gave me a borrowed tongue.

He planted a flag & dispensed

what made up his brain. Start

small & end larger. Expansion

is a uniform my lineage can’t shirk.

The water is enclosing, body

thinning in a baptism of English.

I could say that colonialism was a disease,

but that would suggest a cure.

Copyright © 2020 by Nabila Lovelace. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on August 21, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

for my grandfather We don’t have heirlooms. Haven’t owned things long enough. We’re hoarding us in our stories. Like October 26—the Oklahoma Quick Stop gas at 90¢ and, in 158 more days, Passion of the Christ in a wildlife refuge with Rabbits foot and Black Capped birds—when Edgar Whetstone shoots himself. Like August 4, 1919. Like Ada Willis births the boy conceived with Boy gone somewhere. Like her prayers and circa 10 years past and Mr. Charlie saying, Edgar reads (you call that clean?) but please, girl, coloreds don’t become doctors. Like Edgar trashed his books. Like served, discharged. Like funeral director close to doctor as it got. Formaldehyde wrecked him like Time to get up out the South Detroit inspect dynamics burn a house down torch the county jail. Like now, October. Like I found, searching the internet, one shot of the asylum’s blurry hall empty but for an organ’s pipes. I saw Edgar deluding hymns rousing the two of us in Rock of Ages followed by Philippians 1:21—to die is gain. No way to prove the claim, you die in dream, you die for real. Our family still hanged from trees. Like if they ever fall, no one will hear it someday for a while.

Copyright © 2019 by Erica Dawson. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on March 29, 2019, by the Academy of American Poets.

Is that Eric Garner worked

for some time for the Parks and Rec.

Horticultural Department, which means,

perhaps, that with his very large hands,

perhaps, in all likelihood,

he put gently into the earth

some plants which, most likely,

some of them, in all likelihood,

continue to grow, continue

to do what such plants do, like house

and feed small and necessary creatures,

like being pleasant to touch and smell,

like converting sunlight

into food, like making it easier

for us to breathe.

Copyright © 2015 by Ross Gay. Reprinted from Split This Rock’s The Quarry: A Social Justice Poetry Database.

You, selling roses out of a silver grocery cart

You, in the park, feeding the pigeons

You cheering for the bees

You with cats in your voice in the morning, feeding cats

You protecting the river You are who I love

delivering babies, nursing the sick

You with henna on your feet and a gold star in your nose

You taking your medicine, reading the magazines

You looking into the faces of young people as they pass, smiling and saying, Alright! which, they know it, means I see you, Family. I love you. Keep on.

You dancing in the kitchen, on the sidewalk, in the subway waiting for the train because Stevie Wonder, Héctor Lavoe, La Lupe

You stirring the pot of beans, you, washing your father’s feet

You are who I love, you

reciting Darwish, then June

Feeding your heart, teaching your parents how to do The Dougie, counting to 10, reading your patients’ charts

You are who I love, changing policies, standing in line for water, stocking the food pantries, making a meal

You are who I love, writing letters, calling the senators, you who, with the seconds of your body (with your time here), arrive on buses, on trains, in cars, by foot to stand in the January streets against the cool and brutal offices, saying: YOUR CRUELTY DOES NOT SPEAK FOR ME

You are who I love, you struggling to see

You struggling to love or find a question

You better than me, you kinder and so blistering with anger, you are who I love, standing in the wind, salvaging the umbrellas, graduating from school, wearing holes in your shoes

You are who I love

weeping or touching the faces of the weeping

You, Violeta Parra, grateful for the alphabet, for sound, singing toward us in the dream

You carrying your brother home

You noticing the butterflies

Sharing your water, sharing your potatoes and greens

You who did and did not survive

You who cleaned the kitchens

You who built the railroad tracks and roads

You who replanted the trees, listening to the work of squirrels and birds, you are who I love

You whose blood was taken, whose hands and lives were taken, with or without your saying

Yes, I mean to give. You are who I love.

You who the borders crossed

You whose fires

You decent with rage, so in love with the earth

You writing poems alongside children

You cactus, water, sparrow, crow You, my elder

You are who I love,

summoning the courage, making the cobbler,

getting the blood drawn, sharing the difficult news, you always planting the marigolds, learning to walk wherever you are, learning to read wherever you are, you baking the bread, you come to me in dreams, you kissing the faces of your dead wherever you are, speaking to your children in your mother’s languages, tootsing the birds

You are who I love, behind the library desk, leaving who might kill you, crying with the love songs, polishing your shoes, lighting the candles, getting through the first day despite the whisperers sniping fail fail fail

You are who I love, you who beat and did not beat the odds, you who knows that any good thing you have is the result of someone else’s sacrifice, work, you who fights for reparations

You are who I love, you who stands at the courthouse with the sign that reads NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE

You are who I love, singing Leonard Cohen to the snow, you with glitter on your face, wearing a kilt and violet lipstick

You are who I love, sighing in your sleep

You, playing drums in the procession, you feeding the chickens and humming as you hem the skirt, you sharpening the pencil, you writing the poem about the loneliness of the astronaut

You wanting to listen, you trying to be so still

You are who I love, mothering the dogs, standing with horses

You in brightness and in darkness, throwing your head back as you laugh, kissing your hand

You carrying the berbere from the mill, and the jug of oil pressed from the olives of the trees you belong to

You studying stars, you are who I love

braiding your child’s hair

You are who I love, crossing the desert and trying to cross the desert

You are who I love, working the shifts to buy books, rice, tomatoes,

bathing your children as you listen to the lecture, heating the kitchen with the oven, up early, up late

You are who I love, learning English, learning Spanish, drawing flowers on your hand with a ballpoint pen, taking the bus home

You are who I love, speaking plainly about your pain, sucking your teeth at the airport terminal television every time the politicians say something that offends your sense of decency, of thought, which is often

You are who I love, throwing your hands up in agony or disbelief, shaking your head, arguing back, out loud or inside of yourself, holding close your incredulity which, yes, too, I love I love

your working heart, how each of its gestures, tiny or big, stand beside my own agony, building a forest there

How “Fuck you” becomes a love song

You are who I love, carrying the signs, packing the lunches, with the rain on your face

You at the edges and shores, in the rooms of quiet, in the rooms of shouting, in the airport terminal, at the bus depot saying “No!” and each of us looking out from the gorgeous unlikelihood of our lives at all, finding ourselves here, witnesses to each other’s tenderness, which, this moment, is fury, is rage, which, this moment, is another way of saying: You are who I love You are who I love You and you and you are who

Copyright © 2017 by Aracelis Girmay. Reprinted from Split This Rock’s The Quarry: A Social Justice Poetry Database.

But there never was a black male hysteria

Breaking & entering wearing glee & sadness

And the light grazing my teeth with my lighter

To the night with the flame like a blade cutting

Me slack along the corridors with doors of offices

Orifices vomiting tears & fire with my two tongues

Loose & shooing under a high-top of language

In a layer of mischief so traumatized trauma

Delighted me beneath the tremendous

Stupendous horrendous undiscovered stars

Burning where I didn’t know how to live

My friends were all the wounded people

The black girls who held their own hands

Even the white boys who grew into assassins

Copyright © 2017 by Terrance Hayes. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on November 15, 2017, by the Academy of American Poets.

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

From The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, published by Knopf and Vintage Books. Copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

Breathe

. As in what if

the shadow is gold

en? Breathe. As in

hale assuming

exhale. Imagine

that. As in first

person singular. Homonym

:![]() . As in subject. As

. As in subject. As

in centeroftheworld as in

mundane. The opposite of spectacle

spectacular. This is just us

breathing. Imagine

normalized respite

gold in shadows

. You have the

right to breathe and remain

. Imagine

that

.

Copyright © 2019 by Rosamond S. King. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 5, 2019, by the Academy of American Poets.

On the train the woman standing makes you understand there are no seats available. And, in fact, there is one. Is the woman getting off at the next stop? No, she would rather stand all the way to Union Station.

The space next to the man is the pause in a conversation you are suddenly rushing to fill. You step quickly over the woman’s fear, a fear she shares. You let her have it.

The man doesn’t acknowledge you as you sit down because the man knows more about the unoccupied seat than you do. For him, you imagine, it is more like breath than wonder; he has had to think about it so much you wouldn’t call it thought.

When another passenger leaves his seat and the standing woman sits, you glance over at the man. He is gazing out the window into what looks like darkness.

You sit next to the man on the train, bus, in the plane, waiting room, anywhere he could be forsaken. You put your body there in proximity to, adjacent to, alongside, within.

You don’t speak unless you are spoken to and your body speaks to the space you fill and you keep trying to fill it except the space belongs to the body of the man next to you, not to you.

Where he goes the space follows him. If the man left his seat before Union Station you would simply be a person in a seat on the train. You would cease to struggle against the unoccupied seat when where why the space won’t lose its meaning.

You imagine if the man spoke to you he would say, it’s okay, I’m okay, you don’t need to sit here. You don’t need to sit and you sit and look past him into the darkness the train is moving through. A tunnel.

All the while the darkness allows you to look at him. Does he feel you looking at him? You suspect so. What does suspicion mean? What does suspicion do?

The soft gray-green of your cotton coat touches the sleeve of him. You are shoulder to shoulder though standing you could feel shadowed. You sit to repair whom who? You erase that thought. And it might be too late for that.

It might forever be too late or too early. The train moves too fast for your eyes to adjust to anything beyond the man, the window, the tiled tunnel, its slick darkness. Occasionally, a white light flickers by like a displaced sound.

From across the aisle tracks room harbor world a woman asks a man in the rows ahead if he would mind switching seats. She wishes to sit with her daughter or son. You hear but you don’t hear. You can’t see.

It’s then the man next to you turns to you. And as if from inside your own head you agree that if anyone asks you to move, you’ll tell them we are traveling as a family.

Originally published in Citizen: An American Lyric (Graywolf Press, 2014). Copyright © by Claudia Rankine. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

let ruin end here

let him find honey

where there was once a slaughter

let him enter the lion’s cage

& find a field of lilacs

let this be the healing

& if not let it be

From Don’t Call Us Dead (Graywolf Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Danez Smith. Used by permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Graywolf Press, www.graywolfpress.org.

Assétou Xango performs at Cafe Cultura in Denver.

“Give your daughters difficult names.

Names that command the full use of the tongue.

My name makes you want to tell me the truth.

My name does not allow me to trust anyone

who cannot pronounce it right.”

—Warsan Shire

Many of my contemporaries,

role models,

But especially,

Ancestors

Have a name that brings the tongue to worship.

Names that feel like ritual in your mouth.

I don’t want a name said without pause,

muttered without intention.

I am through with names that leave me unmoved.

Names that leave the speaker’s mouth unscathed.

I want a name like fire,

like rebellion,

like my hand gripping massa’s whip—

I want a name from before the ships

A name Donald Trump might choke on.

I want a name that catches you in the throat

if you say it wrong

and if you’re afraid to say it wrong,

then I guess you should be.

I want a name only the brave can say

a name that only fits right in the mouth of those who love me right,

because only the brave

can love me right

Assétou Xango is the name you take when you are tired

of burying your jewels under thick layers of

soot

and self-doubt.

Assétou the light

Xango the pickaxe

so that people must mine your soul

just to get your attention.

If you have to ask why I changed my name,

it is already too far beyond your comprehension.

Call me callous,

but with a name like Xango

I cannot afford to tread lightly.

You go hard

or you go home

and I am centuries

and ships away

from any semblance

of a homeland.

I am a thief’s poor bookkeeping skills way from any source of ancestry.

I am blindly collecting the shattered pieces of a continent

much larger than my comprehension.

I hate explaining my name to people:

their eyes peering over my journal

looking for a history they can rewrite

Ask me what my name means...

What the fuck does your name mean Linda?

Not every word needs an English equivalent in order to have significance.

I am done folding myself up to fit your stereotype.

Your black friend.

Your headline.

Your African Queen Meme.

Your hurt feelings.

Your desire to learn the rhetoric of solidarity

without the practice.

I do not have time to carry your allyship.

I am trying to build a continent,

A country,

A home.

My name is the only thing I have that is unassimilated

and I’m not even sure I can call it mine.

The body is a safeless place if you do not know its name.

Assétou is what it sounds like when you are trying to bend a syllable

into a home.

With shaky shudders

And wind whistling through your empty,

I feel empty.

There is no safety in a name.

No home in a body.

A name is honestly just a name

A name is honestly just a ritual

And it still sounds like reverence.

Copyright © 2017 Assétou Xango. Used with permission of the poet. Published in Poem-a-Day on June 9, 2020.

For Uncle Paul N’nem

hell nah over my dead—i paid mine. I checked

Black & subtraction knows what it did. made Black

a box to check. subtraction doesn’t know how even

a sigh seasons the roux & the second breath my mother

was always trying to catch. american. emergency.

subtraction doesn’t know Black’s many bodies & body’s

of water. though subtraction does. sunken. gifting the sea’s

new strange stones. subtraction reopened the barbershops &

bowling alleys. insists church. sent us home with inhalers &

half-assed sentences: in god - we - the people - vs - degradation

vs - a new packaged deliverance. homicide. hallelujah.

i’ll be damned. i’ll be back before i’ll be buried. i been Black

& ain’t slept since. subtraction needs my blood to water

their weapons to subtract my blood. do you see the necessity

for dreaming? or else the need to stay awake. to watch. worried.

the hand. invisible. make a peace sign. then a pistol.

Copyright © 2020 by Donte Collins. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 10, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

’Tis a time for much rejoicing;

Let each heart be lured away;

Let each tongue, its thanks be voicing

For Emancipation Day.

Day of victory, day of glory,

For thee, many a field was gory!

Many a time in days now ended,

Hath our fathers’ courage failed,

Patiently their tears they blended;

Ne’er they to their, Maker, railed,

Well we know their groans, He numbered,

When dominions fell, asundered.

As of old the Red Sea parted,

And oppressed passed safely through,

Back from the North, the bold South, started,

And a fissure wide she drew;

Drew a cleft of Liberty,

Through it, marched our people free.

And, in memory, ever grateful,

Of the day they reached the shore,

Meet we now, with hearts e’er faithful,

Joyous that the storm is o’er.

Storm of Torture! May grim Past,

Hurl thee down his torrents fast.

Bring your harpers, bring your sages,

Bid each one the story tell;

Waft it on to future ages,

Bid descendants learn it well.

Kept it bright in minds now tender,

Teach the young their thanks to render.

Come with hearts all firm united,

In the union of a race;

With your loyalty well plighted,

Look your brother in the face,

Stand by him, forsake him never,

God is with us now, forever.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on June 19, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Nobody wants to die on the way

caught between ghosts of whiteness

and the real water

none of us wanted to leave

our bones

on the way to salvation

three planets to the left

a century of light years ago

our spices are separate and particular

but our skins sing in complimentary keys

at a quarter to eight mean time

we were telling the same stories

over and over and over.

Broken down gods survive

in the crevasses and mudpots

of every beleaguered city

where it is obvious

there are too many bodies

to cart to the ovens

or gallows

and our uses have become

more important than our silence

after the fall

too many empty cases

of blood to bury or burn

and there will be no body left

to listen

and our labor

has become more important

than our silence

Our labor has become

more important

than our silence.

Copyright © 1978 by Audre Lorde, from THE COLLECTED POEMS OF AUDRE LORDE by Audre Lorde. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

I suppose I should place them under separate files

Both died from different circumstances kind of, one from HIV AIDS and possibly not having

taken his medicines

the other from COVID-19 coupled with

complications from an underlying HIV status

In each case their deaths may have been preventable if one had taken his meds and the

hospital thought to treat the other

instead of sending him home saying, He wasn’t sick enough

he died a few days later

They were both mountains of men

dark black beautiful gay men

both more than six feet tall fierce and way ahead of their time

One’s drag persona was Wonder Woman and the other started a black fashion magazine

He also liked poetry

They both knew each other from the same club scene we all grew up in

When I was working the door at a club one frequented

He would always say to me haven’t they figured out you’re a star yet

And years ago bartending with the other when I complained about certain people and

treatment he said sounds like it’s time for you to clean house

Both I know were proud of me the poet star stayed true to my roots

I guess what stands out to me is that they both were

gay black mountains of men

Cut down

Felled too early

And it makes me think the biggest and blackest are almost always more vulnerable

My white friend speculates why the doctors sent one home

If he had enough antibodies

Did they not know his HIV status

She approaches it rationally

removed from race as if there were any rationale for sending him home

Still she credits the doctors for thinking it through

But I speculate they saw a big black man before them

Maybe they couldn’t imagine him weak

Maybe because of his size color class they imagined him strong

said he’s okay

Which happened to me so many times

Once when I’d been hospitalized at the same time as a white girl

she had pig-tails

we had the same thing but I saw how tenderly they treated her

Or knowing so many times in the medical system I would never have been treated so terribly if I

had had a man with me

Or if I were white and entitled enough to sue

Both deaths could have been prevented both were almost first to fall in this season of death

But it reminds me of what I said after Eric Garner a large black man was strangled to death over

some cigarettes

Six cops took him down

His famous lines were I can’t breathe

so if we are always the threat

To whom or where do we turn for protection?

Copyright © 2020 by Pamela Sneed. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 18, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Motivated forgetting is a psychological defense mechanism whereby people cope with threatening and unwanted memories by suppressing them from consciousness.

—Amy N. Dalton and Li Huang

in Badagry there is a hung-

ry well of water and memory

loss. in Badagry there was a well

of people lost across a haven

of water. in Badagry there was

a port overwhelmed in un-return.

to omit within the mind is to ebb

heavenward. memory is a wealth

choking the brain in un-respons-

ibility. violence in the mind and

the mind forgets in order to remember

the self before the violence begot.

in Badagry trauma washes ungod-

ly memory heavenward. in Bad-

agry there is an attenuation well

meant to wish away a passage,

meant to unhaven a people.

violence is underwhelming

in return. what the body eats,

the mind waters. responsible

is the memory for un-remittal.

royal is the body for return. god is

the mind for wafting. forgetting

is a port homeward. in Bad-

agry hungry memory grows angry.

in Badagry the memories un-

choke. trauma un-eats the royal.

in Badagry there is a heaven

of people responsible for the birth-

right of remembering, for the well

of us across a haven of water

overwhelmed in un-return.

Copyright © 2020 by Porsha Olayiwola. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 17, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

You are in the black car burning beneath the highway

And rising above it—not as smoke

But what causes it to rise. Hey, Black Child,

You are the fire at the end of your elders’

Weeping, fire against the blur of horse, hoof,

Stick, stone, several plagues including time.

Chrysalis hanging on the bough of this night

And the burning world: Burn, Baby, burn.

Anvil and iron be thy name, yea though ye may

Walk among the harnessed heat and huntsmen

Who bear their masters’ hunger for paradise

In your rabbit-death, in the beheading of your ghost.

You are the healing snake in the heather

Bursting forth from your humps of sleep.

In the morning, your tongue moves along the earth

Naming hawk sky; rabbit run; your tongue,

Poison to the filthy democracy, to the gold-

Domed capitols where the ‘Guard in their grub-

Worm-colored uniforms cling to the blades of grass—

Worm on the leaf, worm in the dust, worm,

Worm made of rust: sing it with me,

Dragon of Insurmountable Beauty.

Black Child, laugh at the men with their hoofs

and borrowed muscle, their long and short guns,

The worm of their faces, their casket ass-

Embling of the afternoon, leftover leaves

From last year’s autumn scraping across their boots;

Laugh, laugh at their assassins on the roofs

(For the time of the assassin is also the time of hysterical laughter).

Black Child, you are the walking-on-of-water

Without the need of an approving master.

You are in a beautiful language.

You are what lies beyond this kingdom

And the next and the next and fire. Fire, Black Child.

Copyright © 2020 by Roger Reeves. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 16, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

for Malcolm Latiff Shabazz

yellow roses in my mother’s room mean

I’m sorry sadness comes in generations

inheritance split flayed displayed

better than all the others

crown weight

the undue burden of the truly exceptional

most special of your kind, a kind of fire

persisting unafraid saffron bloom

to remind us of fragility or beauty or revolution

to ponder darkly in the bright

the fate of young kings

the crimes for which there are no apologies.

Copyright © 2020 by Kristina Kay Robinson. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 23, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

the slight angling up of the forehead

neck extension quick jut of chin

meeting the strangers’ eyes

a gilded curtsy to the sunfill in another

in yourself tithe of respect

in an early version the copy editor deleted

the word “head” from the title

the copy editor says it’s implied

the copy editor means well

the copy editor means

she is only fluent in one language of gestures

i do not explain i feel sad for her

limited understanding of greetings & maybe

this is why my acknowledgements are so long;

didn’t we learn this early?

to look at white spaces

& find the color

thank god o thank god for

you

are here.

Copyright © 2020 by Elizabeth Acevedo. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 22, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Last night, I visited a captivity story.

I was sitting in a lean-to made of bark

with Ella Ruth, both of us teenagers—

her ebony skin, her black hair touching

her tailbone. I looked at her hard, &

she came back to sit beside the fire.

From a slit in the rawhide doorway

I could see my tribe in surgical masks,

& as dogs began to howl I woke up.

Strange how the mind finds tenderness

even in captivity. Or how amidst

this being held in isolation we dream

of masks. I see my ancestors, too,

at the Carnival of Venice, a bouquet

of myrrh, viper flesh, & honey

in the plague doctor’s long beak—

the face of death meant to ward off death.

They look back through the silver mirror.

Remember traveling to Siena,

& we entered that semi-dark room?

Those strange garments—the garb

worn by a secret society of men—

men who wore what we thought

were pale KKK robes & masks.

But they had cared for the contagious

sick, & escorted them to the here

& after, their faces always hidden.

Yes, we descended the Ospedale’s

winding stairs stories underground,

through a long hall to a hidden room

where a small medieval oil painting hung,

the Confraternity of the Night Oratory,

St. Catherine of Siena holds the brothers,

their faces coved in hoods & white robes,

under her cloak. They worked shifts

on behalf of the many struck with plague.

The hooded prisoners were led behind

medieval-thick walls, into their tiny cells

where solitary penitence was paid twenty-

three hours a day. No one dared to speak

at the Eastern State Penitentiary, eyes

staring always at the cold stone floors.

Beans, flourless bread, shad, lobster,

corn, peppers, & a few grains of salt.

Now, Al Capone had a rug & a radio.

On a poor man’s cell block, uncle Gussie,

who robbed a bank, spent years

in the prison built like a wagon wheel.

The low cell door forced him to bow

when entering; the skylight above—

the Eye of God—a reminder he was watched.

When his mother died, two brothers,

a priest & a cop, left sepia photographs

of the funeral. Now, cats & ghosts roam.

Lord, this big country. Land of plentitude

ravaged, heart & gut torn out in the name

of civilization & progress, & just plain old

unsung unction, low-down skullduggery

& theurgy. Nature ripped out by thew

toned in old world prisons. Horsepower.

Even with hard times here, hug the moon

devastatingly close, & beat down the door

with true love. Wherever you are, bless us.

Yeah, we’ve both known a few in the joint,

robbing Peter to pay Paul, or caught

blowing time with this one or that one.

Some excuse to keep rats on a wheel, or in a cage.

Look, time moves at least twice at once now—

back & forth, slow & fast. I held my palm

on my father’s back when he bent to whisper

in the ear of the dead, & two men in black

draped a white handkerchief over a face.

Copyright © 2020 by Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 12, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Last night, I visited a captivity story.

I was sitting in a lean-to made of bark

with Ella Ruth, both of us teenagers—

her ebony skin, her black hair touching

her tailbone. I looked at her hard, &

she came back to sit beside the fire.

From a slit in the rawhide doorway

I could see my tribe in surgical masks,

& as dogs began to howl I woke up.

Strange how the mind finds tenderness

even in captivity. Or how amidst

this being held in isolation we dream

of masks. I see my ancestors, too,

at the Carnival of Venice, a bouquet

of myrrh, viper flesh, & honey

in the plague doctor’s long beak—

the face of death meant to ward off death.

They look back through the silver mirror.

Remember traveling to Siena,

& we entered that semi-dark room?

Those strange garments—the garb

worn by a secret society of men—

men who wore what we thought

were pale KKK robes & masks.

But they had cared for the contagious

sick, & escorted them to the here

& after, their faces always hidden.

Yes, we descended the Ospedale’s

winding stairs stories underground,

through a long hall to a hidden room

where a small medieval oil painting hung,

the Confraternity of the Night Oratory,

St. Catherine of Siena holds the brothers,

their faces coved in hoods & white robes,

under her cloak. They worked shifts

on behalf of the many struck with plague.

The hooded prisoners were led behind

medieval-thick walls, into their tiny cells

where solitary penitence was paid twenty-

three hours a day. No one dared to speak

at the Eastern State Penitentiary, eyes

staring always at the cold stone floors.

Beans, flourless bread, shad, lobster,

corn, peppers, & a few grains of salt.

Now, Al Capone had a rug & a radio.

On a poor man’s cell block, uncle Gussie,

who robbed a bank, spent years

in the prison built like a wagon wheel.

The low cell door forced him to bow

when entering; the skylight above—

the Eye of God—a reminder he was watched.

When his mother died, two brothers,

a priest & a cop, left sepia photographs

of the funeral. Now, cats & ghosts roam.

Lord, this big country. Land of plentitude

ravaged, heart & gut torn out in the name

of civilization & progress, & just plain old

unsung unction, low-down skullduggery

& theurgy. Nature ripped out by thew

toned in old world prisons. Horsepower.

Even with hard times here, hug the moon

devastatingly close, & beat down the door

with true love. Wherever you are, bless us.

Yeah, we’ve both known a few in the joint,

robbing Peter to pay Paul, or caught

blowing time with this one or that one.

Some excuse to keep rats on a wheel, or in a cage.

Look, time moves at least twice at once now—

back & forth, slow & fast. I held my palm

on my father’s back when he bent to whisper

in the ear of the dead, & two men in black

draped a white handkerchief over a face.

Copyright © 2020 by Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 12, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

with a line from Gwendolyn Brooks

Months into the plague now,

I am disallowed

entry even into the waiting

room with Mom, escorted outside

instead by men armed

with guns & bottles

of hand sanitizer, their entire

countenance its own American

metaphor. So the first time

I see you in full force,

I am pacing maniacally

up & down the block outside,

Facetiming the radiologist

& your mother too,

her arm angled like a cellist’s

to help me see.

We are dazzled by the sight

of each bone in your feet,

the pulsing black archipelago

of your heart, your fists in front

of your face like mine when I

was only just born, ten times as big

as you are now. Your great-grandmother

calls me Tyson the moment she sees

this pose. Prefigures a boy

built for conflict, her barbarous

and metal little man. She leaves

the world only months after we learn

you are entering into it. And her mind

the year before that. In the dementia’s final

days, she envisions herself as a girl

of seventeen, running through fields

of strawberries, unfettered as a king

-fisher. I watch your stance and imagine

her laughter echoing back across the ages,

you, her youngest descendant born into

freedom, our littlest burden-lifter, world

-beater, avant-garde percussionist

swinging darkness into song.

Copyright © 2020 by Joshua Bennett. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 24, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

A prison is the only place that’s a prison.

Maybe your brain is a beehive—or, better:

an ants nest? A spin class?

The sand stuck in an hourglass? Your brain is like

stop it. So you practice driving with your knees,

you get all the way out to the complex of Little League fields,

you get chicken fingers with four kinds of mustard—

spicy, whole grain, Dijon, yellow—

you walk from field to field, you watch yourself

play every position, you circle each identical game,

each predictable outcome. On one field you catch.

On one field you pitch. You are center field. You are left.

Sometimes you have steady hands and French braids.

Sometimes you slide too hard into second on purpose.

It feels as good to get the bloody knee as it does to kick yourself in the shin.

You wait for the bottom of the ninth to lay your blanket out in the sun.

Admit it, Sasha, the sun helps. Today,

the red team hits the home run. Red floods every field.

A wasp lands on your thigh. You know this feeling.

Copyright © 2020 by Sasha Debevec-McKenney. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 26, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

When I rise up above the earth,

And look down on the things that fetter me,

I beat my wings upon the air,

Or tranquil lie,

Surge after surge of potent strength

Like incense comes to me

When I rise up above the earth

And look down upon the things that fetter me.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on February 10, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets.

Glory of plums, femur of Glory.

Glory of ferns

on a dark platter.

Glory of willows, Glory of Stag beetles

Glory of the long obedience

of the kingfisher.

Glory of waterbirds, Glory

of thirst.

Glory of the Latin

of the dead and their grammar

composed entirely of decay.

Glory of the eyes of my father

which, when he died, closed

inside his grave,

and opened even more brightly

inside me.

Glory of dark horses

running furiously

inside their own

dark horses.

Copyright © 2020 by Gbenga Adesina. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 25, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

28. It Is Not As If

It is not as if I have not been thinking this,

and it is not as if we have not been thinking this.

For what I mean when I will say whiteness, when I will say white

people, when I say the whites with such seeming assurance,

with such total confidence in the clarity of this locution,

as if we all know the etymology of this word’s genealogy,

the lie of a cluster of marauding nations, building kingdoms

by destroying kingdoms, we have heard this all before, O Babylon.

So, yes, when I say this, what I mean is Babylon, as the Rastas

have constructed the notion, in the way of generosity,

in the way of judgement, in the way of naming the enemy

of history for who he is, in the inadequate way of symbols,

in the way of the bible’s total disregard for history, and the prophet’s

dance in the fulcrum of history, leaping over time and place,

returning to the place where we began having learned

nothing and yet having learned everything language offers us.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

It is not as if we have not been thinking this.

And I want to rehearse Thomas Jefferson and the pragmatism

of cost, the wisdom of his loyalty to his family’s wealth,

the seat of the landed aristocrats reinvented on the plains

of the New World, the coat of arms, the courtly ambitions,

the inventions, the art, the bottles of wine, the French tongue,

the legacy, the faux Roman, faux Greek pretension, the envy

of the nobility of native confederacies, their tongues of fire;

the land, the land, the land, and the property of black bodies,

so much to give up, and who bears the sacrifice, who pays

the cost for the preservation of a nation’s ambitions?

How he said no to freeing the bodies he said were indebted

to him for their every breath—the calculus of property;

oh, the rituals of flesh-mongering, the protection of white freedom.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

It is not as if we have not been thinking this,

And Bartholomew de las Casas, Bishop of Chiapas,

and his Memorial de Remedios para Las Indias,

the pragmatic use of Africans, the ones to carry the burden

of saving the Indians, to save the white man’s soul—

this little bishop of pragmatic calculation, correcting sins

with more sins. And the bodies of black slave women,

their wombs, studied, tested, reshaped, probed, pierced, tortured,

with the whispered promise: “It will help you, too, it really

will and you will be praised for teaching us how to save

the wombs of white women, for the cause, all for the cause.”

And Roosevelt and his unfinished revolution, O “dream deferred”,

O Langston, you tried to sing, how long, not long, how long,

so long! And Churchill’s rising rhetoric, saying that though cousin

Nazis may ritualize the ancient blood feuds by invading Britain,

her world-wide empire will rise up and pay the price for protecting

the kingdom, the realm, liberty, and so on and so forth. Everyone

so merciful, everyone so wounded with guilt and gratitude,

everyone so pragmatic. It is what I am saying, that I am saying

nothing new, and what I am singing is, Babylon yuh throne gone

down, gone down, / Babylon yuh throne gone down.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

It is not as if we have not been thinking this.

For no one is blessed with blindness here,

No one is blessed with deafness here.

And this thing we see is lurking inside the soft

alarm of white people who know that they are watching

a slow magical act of erasure, and they know that this is how

terror manifests itself, quietly, reasonably, and with deadly

intent. They are letting black people die. They are letting

black people die in America. Hidden inside the maw

of these hearts, is the sharp pragmatism of the desperate,

the writers of the myth of survival of the fittest,

or the order of the universe, of Platonic logic, the caste system,

the war of the worlds. They are letting black people die.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

No, it is not as if we have not been thinking this.

And someone is saying, in that soft voice of calm,

“Well, there will be costs, and those are the costs

of our liberty.” Remember when the century turned,

and the pontiff and pontificators declared that in fifty years,

the nation would be brown, and for a decade, the rogue people

sought to halt this with guns, with terror, with the shutting of borders?

Now this has arrived, a kind of gift. Let them die. The blacks,

the poor, the ones who multiply like flies, let them die, and soon

we will be lily white again. Do you think I am paranoid? I am.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

It is not as if we have not been thinking this.

And paranoia is how we’ve survived. So, we must march in the streets,

force the black people who are immigrant nurses, who are meat packers,

who are street cleaners, who are short-order cooks, who are

the dregs of society, who are black, who are black, who are black.

Let them die. Here in Nebraska, our governor would not release

the racial numbers. He says there is no need to cause strife,

this is not our problem, he says. We are better than this, he says.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

It is not as if we have not been thinking this.

And so in the silence, we do not know what the purgation is,

and here in this stumbling prose of mine, this blunt prose of mine,

is the thing I have not yet said, “They are trying to kill us,

they are trying to kill us, they are trying to kill us off.”

I sip my comfort. The dead prophet, his voice broken by cancer,

his psalm rises over the darkening plains, “Oh yeah, natty Congo”,

and then the sweetest act of pure resistance, “Spread out! Spread out!

Spread out!” We are more than sand on the seashore, so we will not

get jumpy, we won’t get bumpy, and we won’t walk away, “Spread out!”,

they sing in four-part harmony, spears out, Spread out! Spread out!

It is not as if I have not been thinking this,

and it is not as if we have not been thinking this.

It is how we survived and how we will continue to survive.

But don’t be fooled. These are the betrayals that are gathering

over the hills. Help me, I say, help me to see this as something else.

It is not as if I have not been thinking this.

See? It is not as if we have not all been thinking this.

KD

29.

It needs to be blunt and said as you say it.

I can see and agree and am trying to act, too,

but am embroiled in the whiteness I detest.

Yes, as a pacifist, I detest that whiteness

and see it as the bleaching of shrouds.

It makes me ashamed and angry and I fall

into nowhere and have no feet and can’t find

my way out of it. My hands are the wrong

shape to hide behind. I see the murderers

and stand in front of them, refusing

everything they are. I am weaponless.

I know guns from my childhood

and know their sick laugh, their

self-certainty, their imitations of ‘sound’—

their chatter. Yes, of course it’s death

they make, even when the target

is a symbol or a bull’s eye—names

say it all, underneath—target shooting,

but it’s not selective at the end of the breathing,

the last bottle of O negative blood, it takes all

in its recoil as much as its impact, it kills

life and it kills death and it is given

an ‘out’ through Keats’s white as death

‘half in love with easeful death’—

a poem I have recited since I was

sixteen, have recited on the verge of death,

as if it was a way through when it wasn’t.

The poem separated from the hand

that wrote it makes a travesty

of reality—the corpses piling

up in the feint light of whiteness.

The poem was part of the problem

born in the eye of empire, the smell

of hospitals and anatomies, and yet

I lament his terrible tragic passing.

I have stood in his deathroom

and only thought of a young person

and their overwhelming death,

the steps flowing with people

as now they are empty of both

Rome and world. I think the same

in the acts of medicine the acts

of insurance and discrimination,

and those who take the brunt of economies,

especially in Western economies

that live off the labour of re-arranged

and redecorated class alienation.

What you say is true and needs

to be said in such a way, Kwame.

I am saying as an aside to all tyranny,

that using the methods of the tyrannical

will lead to ongoing tyranny. Refusal

to do anything for them, to stop using their goods,

to stop giving them anything at all, will soon bring their collapse.

Total and utter refusal. But then, they are

even prepared for that—bringing

it all down makes the suffering

suffer more via the pain ‘brought

on themselves.’ That’s tyranny’s propaganda.

White bigots and the bigotry

implicit in any notion of ‘whiteness’

search for validation even where

it is bluntly refused—they enforce

their validation, legitimise themselves

in every conversation. I guess

that might be what Spike Lee

and Chuck D. have been saying

forever—the very notion

‘white folk’ have any rights

of control or even say in other

people’s (and peoples’) lives needs

undoing. Your poem helps protect

the vulnerable and thwart the murderous—confront

them with its declarations of blackness,

and that’s as it must be, and you must say,

given the traumatic reality, Kwame.

So I listen to Sly Dunbar

not to absorb into what I have

been made from, but to reflect

against and learn from—to learn

is to respect and not just

be awed and entertained, those

shrouds across creativity,

those thefts as deadly

as going armed

with intent. I have literally

placed flowers in the barrels of guns.

I will stand between the gun

and its victim, I will

bury the arms

deeper than rust,

the corrosion,

beyond even air

of the grave, beyond

anything organic, living.

People are meant

to live! I march with you,

I am with you, I stand by you.

I am not you. I know.

JK

Copyright © 2020 by Kwame Dawes and John Kinsella. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 11, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Dear Reader, it wouldn’t be a lie if you said poetry was a cover

for my powerlessness, here, on this plane

having ticked off another day waiting for her diagnosis to rise.

As the air pressure picks up, I feel the straight road

curved by darkness, where the curve is a human limit,

where the second verb is mean, the second verb is to blind.

On the other line, my mother sits on her bed

after a terrible infection. Her voice like a wave

breaking through the receiver, when she tells me

that unlike her I revel in the inconclusivity of the body.

+

At the end of the line, I know my mother

accumulates organ-shaped pillows after surgery.

First a heart, then lungs.

The lung pillow is a fleshy-pink. The heart

pillow, a child-drawn metaphor. Both help her expectorate

the costs to the softer places of her body.

After each procedure they make her cross,

the weight of the arm comes down. These souvenirs

of miraculous stuffing other patients on the transplant floor covet,

the way one might long for a paper sack doll made by hand.

Though the stuffing is just wood shavings, one lies

with the doll tight at the crick of an elbow at night.

Copyright © 2020 by April Freely. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 29, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

If space makes the pattern, her absence is filling a quota.

The president says,

“we’re a nation of laws” :—

The limerick

under her dreaming :—that lilting.

At seven

a Seuss-rhyme’s still funny.

And who’s to say wouldn’t have been, still, at 30?

The Sneetches or What Was I Scared Of?

She’s seven, asleep on the living room sofa.

] in amphibrachs—:

who hears her

breathing? [

If space makes the pattern, her absence is filling a quota.

This absence—: Aiyana.

But what was the officer scared of?

What reaches for him in the recesses of

his attention?

What formal suggestion of

darkness needs stagger

to formless?

If space makes the pattern—:

egregious—:

This grief in the rhythm of—: uplift too

graphic—:

a measure of struggle.

Which struggle with law

holds the dark in it? Keeps

the dark of

Quinletta, LaToya, Kimkesia, Oneka, Natasha, Breonna…

my still-breathing cousins

] your still-breathing cousins [

alive in it. Aiyana. Her breath in perfection—:

at seven—: This measure for measure on measure on measure

or else—:

︶

Law is dead, Aiyana. It never was

Copyright © 2020 by Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 2, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

State of Florida v. Patrick Gene Scarborough, David Erwin Beagles, Ollie Odell Stoutamire, William Ted Collinsworth, 1959, case #3445.

Later I lower my head to my father’s chest,

the hollow where I hear his heart stop, if stop

meant speed to a stop, if hearts could gasp like a

a mouth when events stun the heart to a stop

for a moment. His eyes fill with anger

then, collecting himself, he rises up to slump

his shoulders back down. The fists. The eyes.

Nothing can raise up, nothing feels essential,

a black body raising up in the south and all…

To a life starting here, ethereal, yet flesh, and all?

And even if you could, what all good would it do?

The damage and all. Black birds flock,

dulcet yet mourning, an uproar of need,

a cry of black but blue is not the sky

in which they gender. My God, if life is not pain,

no birth brought me into this world,

or could life begin here where it ends—

no shelter, no comfort, no ride home—

and must I go on, saying more? Pointing

them out in a court of men? Didn’t

the trees already finger the culprits? Creatures

make a way where there is no way. That way

after I lean into what’s left of me—and must I

(yes, you must) explain, over and over,

how my blood came to rest here—my body,

now labeled evidence, sows what I have yet to say.

Copyright © 2020 by A. Van Jordan. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 30, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Because there is too much to say

Because I have nothing to say

Because I don’t know what to say

Because everything has been said

Because it hurts too much to say

What can I say what can I say

Something is stuck in my throat

Something is stuck like an apple

Something is stuck like a knife

Something is stuffed like a foot

Something is stuffed like a body

Copyright © 2020 by Toi Derricotte. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 3, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

What is water but rain but cloud but river but ocean

but ice but tear.

What is tear but torn what is worn as skin as in as out

as out.

Exodus. I am trying to tell a tale that shifts like a gale

that hurricanes and casts a line

that buckles in wind that is reborn a kite a wing.

I am far

from the passage far from the plane of descending

them,

suitcases passports degrees of mobility like heat

like heat on their backs.

This cluster of fine grapes Haitian purple beige

black brown.

Copyright © 2020 by Danielle Legros Georges. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 8, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

I choose Rhythm,

the beginning as motion,

black Funk shaping itself

in the time before time,

dark, glorious and nimble as a sperm

sparkling its way into the greatest of grooves,

conjuring worlds from dust and storm and primordial soup.

I accept the Funk as my holy savior,

Funk so high you can’t get over it,

so wide you can’t get around it,

ubiquitous Funk that envelopes all creatures great and small,

quickens nerve endings and the white-hot

hearts of stars.

I believe in Rhythm rippling each feather on a sparrow’s back

and glittering in every grain of sand,

I am faithful to Funk as irresistible twitch, heart skip

and backbone slip,

the whole Funk and nothing but the Funk

sliding electrically into exuberant noise.

I hear the cosmos swinging

in the startled whines of newborns,

the husky blare of tenor horns,

lambs bleating and lions roaring,

a fanfare of tambourines and glory.

This is what I know:

Rhythm resounds as a blessing of the body,

the wonder and hurt of being:

the wet delight of a tongue on a thigh

fear inching icily along a spine

the sudden surging urge to holler

the twinge that tells your knees it’s going to rain

the throb of centuries behind and before us

I embrace Rhythm as color and chorus,

the bright orange bloom of connection,

the mahogany lure of succulent loins

the black-and-tan rhapsody of our clasping hands.

I whirl to the beat of the omnipotent Hum;

diastole, systole, automatic,

borderless. Bigger and bigger still:

Bigger than love,

Bigger than desire or adoration.

Bigger than begging and contemplation.

Bigger than wailing and chanting and the slit throats of roosters.

For which praise is useless.

For which gratitude might as well be whispered.

For which motion is meaning enough.

Funk lives in us, begetting light as bright as music

unfolding into dear lovely day

and bushes ablaze in

Rhythm. Until it begins again.

Copyright © 2020 by Jabari Asim. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 6, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

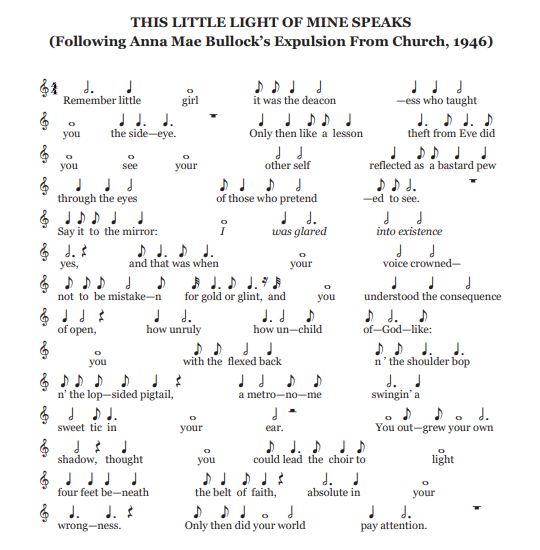

I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired

She meant

No more turned cheek

No more patience for the obstruction

of black woman’s right to vote

& plant & feed her family

She meant

Equality will cost you your luxurious life

If a Black woman can’t vote

If a brown baby can’t be fed

If we all don’t have the same opportunity America promised

She meant

Ain’t no mountain boulder enough

to wan off a determined woman

She meant

Here

Look at my hands

Each palm holds a history

of the 16 shots that chased me

harm free from a plantation shack

Look at my eyes

Both these are windows

these little lights of mine

She meant

Nothing but death can stop me

from marching out a jail cell still a free woman

She meant

Nothing but death can stop me from running for Congress

She meant

No black jack beating will stop my feet from working

& my heart from swelling

& my mouth from praying

She meant

America! you will learn freedom feels like

butter beans, potatoes & cotton seeds

picked by my sturdy hands

She meant

Look

Victoria Gray, Anna Divine & Me

In our rightful seats on the house floor

She meant

Until my children

& my children’s children

& they babies too

can March & vote

& get back in interest

what was planted

in this blessed land

She meant

I ain’t stopping America

I ain’t stopping America

Not even death can take away from my woman’s hands

what I’ve rightfully earned

Copyright © 2019 by Mahogany Browne. Originally featured in Vibe. Used with permission of the author.

I ask a student how I can help her. Nothing is on her paper.

It’s been that way for thirty-five minutes. She has a headache.

She asks to leave early. Maybe I asked the wrong question.

I’ve always been dumb with questions. When I hurt,

I too have a hard time accepting advice or gentleness.

I owe for an education that hurt, and collectors call my mama’s house.

I do nothing about my unpaid bills as if that will help.

I do nothing about the mold on my ceiling, and it spreads.

I do nothing about the cat’s litter box, and she pisses on my new bath mat.

Nothing isn’t an absence. Silence isn’t nothing. I told a woman I loved her,

and she never talked to me again. I told my mama a man hurt me,

and her hard silence told me to keep my story to myself.

Nothing is full of something, a mass that grows where you cut at it.

I’ve lost three aunts when white doctors told them the thing they felt

was nothing. My aunt said nothing when it clawed at her breathing.

I sat in a room while it killed her. I am afraid when nothing keeps me

in bed for days. I imagine what my beautiful aunts are becoming

underground, and I cry for them in my sleep where no one can see.

Nothing is in my bedroom, but I smell my aunt’s perfume

and wake to my name called from nowhere. I never looked

into a sky and said it was empty. Maybe that’s why I imagine a god

up there to fill what seems unimaginable. Some days, I want to live

inside the words more than my own black body.

When the white man shoves me so that he can get on the bus first,

when he says I am nothing but fits it inside a word, and no one stops him,

I wear a bruise in the morning where he touched me before I was born.

My mama’s shame spreads inside me. I’ve heard her say

there was nothing in a grocery store she could afford. I’ve heard her tell

the landlord she had nothing to her name. There was nothing I could do

for the young black woman that disappeared on her way to campus.

They found her purse and her phone, but nothing led them to her.

Nobody was there to hold Renisha McBride’s hand

when she was scared of dying. I worry poems are nothing against it.

My mama said that if I became a poet or a teacher, I’d make nothing, but

I’ve thrown words like rocks and hit something in a room when I aimed

for a window. One student says when he writes, it feels

like nothing can stop him, and his laughter unlocks a door. He invites me

into his living.

Copyright © 2020 by Krysten Hill. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 7, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Is there a place where black men can go

to be beautiful? Is there light there? Touch?

Is there comfort or room to raise their black

sons as anything other than a future asterisk,

at risk to be asteroid or rogue planet but not

comet—to be studded with awe and clamor

and admired for radial trajectories across

a dark sky made of asphalt and moonshine

to be celebs and deemed a magnificent sight?

Copyright © 2020 by Enzo Silon Surin. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 10, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

"Their colour is a diabolic die."

—Phillis Wheatley

What they say they are

And what they actually do

Is what Phillis overhears.

It’s like she isn’t there.

It’s like she’s a ghost, at arm’s length, hearing

The living curse out the dead—

Which, she’s been led to believe

No decent person does in a church.

How they say they love her

And how they look at her

Is what Phillis observes;

Like she’s the hole in the pocket

After the money rolls out.

God loves everybody—even the sinner,

(they say)

Even a mangy hound can rely

On a scrap of meat, scraped off the plate

(they say).

What they testify

And what they whisper in earshot

Is as dark as her skin, whistled from opposite sides

Of a mouth.

Is she the bible’s fine print?

Copyright © 2020 by Cornelius Eady. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 15, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

—Milledgeville, Georgia 18581

The hand2 in which the laws of the land3

were penned was that of a white man.

Hand, servant, same as bondsman, slave,

and necessarily a negro4 in this context,

but not all blacks were held in bondage

though bound by the constructed fetters

of race—that expedient economic tool

for making a class of women and men

kept in place based on the color writ

across their faces—a conservative notion

for keeping power in the hands of the few5.

It kept the threat held over the heads of all

negroes, including those free blacks,

who after the coming war would be

called the formerly free people of color

once we were all ostensibly free.

Hands, enslaved, handled clay

and molds in the making of bricks

to build this big house for the gathering

of those few men with their white faces

who hold power like the end of the rope.

Hand, what’s needed to wed, and a ring

or broom. Hand, a horse measure, handy

in horse-trading6. We also call the pointers

on the clock that go around marking time

in this occidental fashion, handy for business

transactions, hands.

1Milledgeville, my hometown, touts itself as the Antebellum Capital and it was that, but it was also, for the duration of the Civil War, the Confederate Capital of Georgia, and where Joseph Emerson Brown, the governor of Georgia from November 6, 1857 till June 17, 1865, lived with his family in the Governor’s Mansion. Governors brought enslaved folks, folks they held as property, from their plantations to work as the household staff at the Governor’s Mansion.

2 Hand as in handwriting, which is awful

in my case, so I type, but way back when,

actually, only 150 years ago—two long-lived

lives—by law few like me had a hand.

3 What’s needed is a note on the laws

that constructed race in the colonies

and young states, but that deserves

a library’s worth of writing.

4 Almost a decade after reading the typescript of a letter written by Elizabeth Grisham Brown, Gov. Joseph Emerson Brown’s wife, I finally got to read the original letter written in her hand; I got to touch it with my hand. I got to verify that she’d written what I’d read in the typescript. I’d thought about this letter she wrote home to her mother and sister at their plantation for near a decade because of its closing sentences: “Hoping you are all well, we will expect to hear from you shortly. Mr. Brown and the children join me in love to you all.” And caught between that and her signing “Yours most affectionately, E. Brown” she writes “The negroes send love to their friends.” Those words in that letter struck me when I first read them and have stuck with me since. There is so much there that speaks to the situation those Black folk were in then and the situation Black folk are in now. I intend for the title of my next book to be The Negroes Send Love to Their Friends.

5And this arrangement also served the rest

who would walk on the white side of the color

line, so they would readily step at the behest

of that narrative of race and their investment

in what is white and Black.

6 Prospective buyers would inspect

Negroes like horses or other livestock

and look in their mouths.

Copyright © 2020 by Sean Hill. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 9, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

after Margaret Walker’s “For My People”

The Lord clings to my hands

after a night of shouting.

The Lord stands on my roof

& sleeps in my bed.

Sings the darkened, Egun tunnel—

cooks my food in abundance,

though I was once foolish

& wished for an emptied stomach.

The Lord drapes me with rolls of fat

& plaits my hair with sanity.

Gives me air,

music from unremembered fever.

This air

oh that i may give air to my people

oh interruption of murder

the welcome Selah

The Lord is a green, Tubman escape.

A street buzzing with concern,

minds discarding answers.

Black feet on a centuries-long journey.

The Lord is the dead one scratching my face,

pinching me in dreams.

The screaming of the little girl that I was,

the rocking of the little girl that I was—

the sweet hush of her healing.

Her syllables

skipping on homesick pink.

I pray to my God of confused love,

a toe touching blood

& swimming through Moses-water.

A cloth & wise rocking.

An eventual Passover,

outlined skeletons will sing

this day of air

for my people—

oh the roar of God

oh our prophesied walking

Copyright © 2020 by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 17, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

your body is still a miracle thirst

quenched with water across dry tongue and lips

or cocoa butter ashy legs immersed

till shine seen sheen the mind too cups and dips

from its favorite rivers figures and facts

slant stories of orbiting protests or

protons around daughters or suns :: it backs

up or opens wide to joy’s gush downpour

the floods the heart pumps hip hop doo wop dub

veins mining the mud for poetry’s o

cell after cell drinks ringgold colors mulled

cool cascades of calla lilies :: swallow

and bathe breathe believe through drought you survive

like the passage schooled you till rains arrive

—after alexis pauline gumbs