On the Erie Canal, it was,

All on a summer’s day,

I sailed forth with my parents

Far away to Albany.

From out the clouds at noon that day

There came a dreadful storm,

That piled the billows high about,

And filled us with alarm.

A man came rushing from a house,

Saying, “Snub up* your boat I pray,

Snub up your boat, snub up, alas,

Snub up while yet you may.”

Our captain cast one glance astern,

Then forward glanced he,

And said, “My wife and little ones

I never more shall see.”

Said Dollinger the pilot man,

In noble words, but few,—

“Fear not, but lean on Dollinger,

And he will fetch you through.”

The boat drove on, the frightened mules

Tore through the rain and wind,

And bravely still, in danger’s post,

The whip-boy strode behind.

“Come ’board, come ’board,” the captain cried,

“Nor tempt so wild a storm;"

But still the raging mules advanced,

And still the boy strode on.

Then said the captain to us all,

“Alas, ’tis plain to me,

The greater danger is not there,

But here upon the sea.

“So let us strive, while life remains,

To save all souls on board,

And then if die at last we must,

Let . . . . I cannot speak the word!”

Said Dollinger the pilot man,

Tow’ring above the crew,

“Fear not, but trust in Dollinger,

And he will fetch you through.”

“Low bridge! low bridge!” all heads went down,

The laboring bark sped on;

A mill we passed, we passed church,

Hamlets, and fields of corn;

And all the world came out to see,

And chased along the shore

Crying, “Alas, alas, the sheeted rain,

The wind, the tempest’s roar!

Alas, the gallant ship and crew,

Can nothing help them more?”

And from our deck sad eyes looked out

Across the stormy scene:

The tossing wake of billows aft,

The bending forests green,

The chickens sheltered under carts

In lee of barn the cows,

The skurrying swine with straw in mouth,

The wild spray from our bows!

“She balances!

She wavers!

Now let her go about!

If she misses stays and broaches to,

We’re all"—then with a shout,

“Huray! huray!

Avast! belay!

Take in more sail!

Lord, what a gale!

Ho, boy, haul taut on the hind mule’s tail!”

“Ho! lighten ship! ho! man the pump!

Ho, hostler, heave the lead!”

“And count ye all, both great and small,

As numbered with the dead:

For mariner for forty year,

On Erie, boy and man,

I never yet saw such a storm,

Or one’t with it began!”

So overboard a keg of nails

And anvils three we threw,

Likewise four bales of gunny-sacks,

Two hundred pounds of glue,

Two sacks of corn, four ditto wheat,

A box of books, a cow,

A violin, Lord Byron’s works,

A rip-saw and a sow.

A curve! a curve! the dangers grow!

“Labbord!—stabbord!—s-t-e-a-d-y!—so!—

Hard-a-port, Dol!—hellum-a-lee!

Haw the head mule!—the aft one gee!

Luff!—bring her to the wind!”

“A quarter-three!—’tis shoaling fast!

Three feet large!—t-h-r-e-e feet!—

Three feet scant!” I cried in fright

“Oh, is there no retreat?”

Said Dollinger, the pilot man,

As on the vessel flew,

“Fear not, but trust in Dollinger,

And he will fetch you through.”

A panic struck the bravest hearts,

The boldest cheek turned pale;

For plain to all, this shoaling said

A leak had burst the ditch’s bed!

And, straight as bolt from crossbow sped,

Our ship swept on, with shoaling lead,

Before the fearful gale!

“Sever the tow-line! Cripple the mules!”

Too late! There comes a shock!

****

Another length, and the fated craft

Would have swum in the saving lock!

Then gathered together the shipwrecked crew

And took one last embrace,

While sorrowful tears from despairing eyes

Ran down each hopeless face;

And some did think of their little ones

Whom they never more might see,

And others of waiting wives at home,

And mothers that grieved would be.

But of all the children of misery there

On that poor sinking frame,

But one spake words of hope and faith,

And I worshipped as they came:

Said Dollinger the pilot man,—

(O brave heart, strong and true!)—

“Fear not, but trust in Dollinger,

For he will fetch you through.”

Lo! scarce the words have passed his lips

The dauntless prophet say’th,

When every soul about him seeth

A wonder crown his faith!

For straight a farmer brought a plank,—

(Mysteriously inspired)—

And laying it unto the ship,

In silent awe retired.

Then every sufferer stood amazed

That pilot man before;

A moment stood. Then wondering turned,

And speechless walked ashore.

*The customary canal technicality for ‘tie up.’

This poem is in the public domain. Taken from Mark Twain's Roughing It.

Surprised by joy—impatient as the Wind I turned to share the transport—Oh! with whom But Thee, deep buried in the silent Tomb, That spot which no vicissitude can find? Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind— But how could I forget thee? Through what power, Even for the least division of an hour, Have I been so beguiled as to be blind To my most grievous loss?—That thought's return Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore, Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn, Knowing my heart's best treasure was no more; That neither present time, nor years unborn Could to my sight that heavenly face restore.

This poem is in the public domain.

Soon as the sun forsook the eastern main

The pealing thunder shook the heav’nly plain;

Majestic grandeur! From the zephyr’s wing,

Exhales the incense of the blooming spring,

Soft purl the streams, the birds renew their notes,

And through the air their mingled music floats.

Through all the heav’ns what beauteous dies are spread!

But the west glories in the deepest red:

So may our breasts with every virtue glow,

The living temples of our God below!

Fill’d with the praise of him who gives the light,

And draws the sable curtains of the night,

Let placid slumbers soothe each weary mind,

At morn to wake more heav’nly, more refin’d;

So shall the labors of the day begin

More pure, more guarded from the snares of sin.

Night’s leaden sceptre seals my drowsy eyes,

Then cease, my song, till fair Aurora rise.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on December 2, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets.

Happy the man, whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air,

In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread,

Whose flocks supply him with attire,

Whose trees in summer yield him shade,

In winter fire.

Blest, who can unconcernedly find

Hours, days, and years slide soft away,

In health of body, peace of mind,

Quiet by day,

Sound sleep by night; study and ease,

Together mixed; sweet recreation;

And innocence, which most does please,

With meditation.

Thus let me live, unseen, unknown;

Thus unlamented let me die;

Steal from the world, and not a stone

Tell where I lie.

This poem is in the public domain.

The instructor said,

Go home and write

a page tonight.

And let that page come out of you—

Then, it will be true.

I wonder if it's that simple?

I am twenty-two, colored, born in Winston-Salem.

I went to school there, then Durham, then here

to this college on the hill above Harlem.

I am the only colored student in my class.

The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem,

through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas,

Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y,

the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator

up to my room, sit down, and write this page:

It's not easy to know what is true for you or me

at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I'm what

I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you:

hear you, hear me—we two—you, me, talk on this page.

(I hear New York, too.) Me—who?

Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being colored doesn't make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be

a part of you, instructor.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That's American.

Sometimes perhaps you don't want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that's true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you're older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

This is my page for English B.

From The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, published by Knopf and Vintage Books. Copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

But most by Numbers judge a Poet's song; And smooth or rough, with them, is right or wrong: In the bright Muse tho' thousand charms conspire, Her voice is all these tuneful fools admire; Who haunt Parnassus but to please their ear, Not mend their minds; as some to church repair, Not for the doctrine but the music there. These equal syllables alone require, Tho' oft the ear the open vowels tire; While expletives their feeble aid do join; And ten low words oft creep in one dull line: While they ring round the same unvary'd chimes, With sure returns of still expected rhymes; Where'er you find "the cooling western breeze," In the next line it "whispers through the trees" If crystal streams "with pleasing murmurs creep" The reader's threaten'd (not in vain) with "sleep": Then, at the last and only couplet fraught With some unmeaning thing they call a thought, A needless Alexandrine ends the song That, like a wounded snake, drags its slow length along.

This poem is in the public domain.

A poem should be palpable and mute

As a globed fruit,

Dumb

As old medallions to the thumb,

Silent as the sleeve-worn stone

Of casement ledges where the moss has grown—

A poem should be wordless

As the flight of birds.

*

A poem should be motionless in time

As the moon climbs,

Leaving, as the moon releases

Twig by twig the night-entangled trees,

Leaving, as the moon behind the winter leaves,

Memory by memory the mind—

A poem should be motionless in time

As the moon climbs.

*

A poem should be equal to:

Not true.

For all the history of grief

An empty doorway and a maple leaf.

For love

The leaning grasses and two lights above the sea—

A poem should not mean

But be.

Copyright © by the Estate of Archibald MacLeish and reprinted by permission of the Estate.

If from great nature's or our own abyss Of thought we could but snatch a certainty, Perhaps mankind might find the path they miss— But then 't would spoil much good philosophy. One system eats another up, and this Much as old Saturn ate his progeny; For when his pious consort gave him stones In lieu of sons, of these he made no bones. But System doth reverse the Titan's breakfast, And eats her parents, albeit the digestion Is difficult. Pray tell me, can you make fast, After due search, your faith to any question? Look back o'er ages, ere unto the stake fast You bind yourself, and call some mode the best one. Nothing more true than not to trust your senses; And yet what are your other evidences? For me, I know nought; nothing I deny, Admit, reject, contemn; and what know you, Except perhaps that you were born to die? And both may after all turn out untrue. An age may come, Font of Eternity, When nothing shall be either old or new. Death, so call'd, is a thing which makes men weep, And yet a third of life is pass'd in sleep. A sleep without dreams, after a rough day Of toil, is what we covet most; and yet How clay shrinks back from more quiescent clay! The very Suicide that pays his debt At once without instalments (an old way Of paying debts, which creditors regret) Lets out impatiently his rushing breath, Less from disgust of life than dread of death. 'T is round him, near him, here, there, every where; And there 's a courage which grows out of fear, Perhaps of all most desperate, which will dare The worst to know it:—when the mountains rear Their peaks beneath your human foot, and there You look down o'er the precipice, and drear The gulf of rock yawns,—you can't gaze a minute Without an awful wish to plunge within it. 'T is true, you don't—but, pale and struck with terror, Retire: but look into your past impression! And you will find, though shuddering at the mirror Of your own thoughts, in all their self-confession, The lurking bias, be it truth or error, To the unknown; a secret prepossession, To plunge with all your fears—but where? You know not, And that's the reason why you do—or do not. But what 's this to the purpose? you will say. Gent. reader, nothing; a mere speculation, For which my sole excuse is—'t is my way; Sometimes with and sometimes without occasion I write what 's uppermost, without delay: This narrative is not meant for narration, But a mere airy and fantastic basis, To build up common things with common places. You know, or don't know, that great Bacon saith, 'Fling up a straw, 't will show the way the wind blows;' And such a straw, borne on by human breath, Is poesy, according as the mind glows; A paper kite which flies 'twixt life and death, A shadow which the onward soul behind throws: And mine 's a bubble, not blown up for praise, But just to play with, as an infant plays. The world is all before me—or behind; For I have seen a portion of that same, And quite enough for me to keep in mind;— Of passions, too, I have proved enough to blame, To the great pleasure of our friends, mankind, Who like to mix some slight alloy with fame; For I was rather famous in my time, Until I fairly knock'd it up with rhyme. I have brought this world about my ears, and eke The other; that 's to say, the clergy, who Upon my head have bid their thunders break In pious libels by no means a few. And yet I can't help scribbling once a week, Tiring old readers, nor discovering new. In youth I wrote because my mind was full, And now because I feel it growing dull. But 'why then publish?'—There are no rewards Of fame or profit when the world grows weary. I ask in turn,—Why do you play at cards? Why drink? Why read?—To make some hour less dreary. It occupies me to turn back regards On what I 've seen or ponder'd, sad or cheery; And what I write I cast upon the stream, To swim or sink—I have had at least my dream. I think that were I certain of success, I hardly could compose another line: So long I 've battled either more or less, That no defeat can drive me from the Nine. This feeling 't is not easy to express, And yet 't is not affected, I opine. In play, there are two pleasures for your choosing— The one is winning, and the other losing. Besides, my Muse by no means deals in fiction: She gathers a repertory of facts, Of course with some reserve and slight restriction, But mostly sings of human things and acts— And that 's one cause she meets with contradiction; For too much truth, at first sight, ne'er attracts; And were her object only what 's call'd glory, With more ease too she 'd tell a different story. Love, war, a tempest—surely there 's variety; Also a seasoning slight of lucubration; A bird's-eye view, too, of that wild, Society; A slight glance thrown on men of every station. If you have nought else, here 's at least satiety Both in performance and in preparation; And though these lines should only line portmanteaus, Trade will be all the better for these Cantos. The portion of this world which I at present Have taken up to fill the following sermon, Is one of which there 's no description recent. The reason why is easy to determine: Although it seems both prominent and pleasant, There is a sameness in its gems and ermine, A dull and family likeness through all ages, Of no great promise for poetic pages. With much to excite, there 's little to exalt; Nothing that speaks to all men and all times; A sort of varnish over every fault; A kind of common-place, even in their crimes; Factitious passions, wit without much salt, A want of that true nature which sublimes Whate'er it shows with truth; a smooth monotony Of character, in those at least who have got any. Sometimes, indeed, like soldiers off parade, They break their ranks and gladly leave the drill; But then the roll-call draws them back afraid, And they must be or seem what they were: still Doubtless it is a brilliant masquerade; But when of the first sight you have had your fill, It palls—at least it did so upon me, This paradise of pleasure and ennui. When we have made our love, and gamed our gaming, Drest, voted, shone, and, may be, something more; With dandies dined; heard senators declaiming; Seen beauties brought to market by the score, Sad rakes to sadder husbands chastely taming; There 's little left but to be bored or bore. Witness those 'ci-devant jeunes hommes' who stem The stream, nor leave the world which leaveth them. 'T is said—indeed a general complaint— That no one has succeeded in describing The monde, exactly as they ought to paint: Some say, that authors only snatch, by bribing The porter, some slight scandals strange and quaint, To furnish matter for their moral gibing; And that their books have but one style in common— My lady's prattle, filter'd through her woman. But this can't well be true, just now; for writers Are grown of the beau monde a part potential: I 've seen them balance even the scale with fighters, Especially when young, for that 's essential. Why do their sketches fail them as inditers Of what they deem themselves most consequential, The real portrait of the highest tribe? 'T is that, in fact, there 's little to describe. 'Haud ignara loquor;' these are Nugae, 'quarum Pars parva fui,' but still art and part. Now I could much more easily sketch a harem, A battle, wreck, or history of the heart, Than these things; and besides, I wish to spare 'em, For reasons which I choose to keep apart. 'Vetabo Cereris sacrum qui vulgarit—' Which means that vulgar people must not share it. And therefore what I throw off is ideal— Lower'd, leaven'd, like a history of freemasons; Which bears the same relation to the real, As Captain Parry's voyage may do to Jason's. The grand arcanum 's not for men to see all; My music has some mystic diapasons; And there is much which could not be appreciated In any manner by the uninitiated. Alas! worlds fall—and woman, since she fell'd The world (as, since that history less polite Than true, hath been a creed so strictly held) Has not yet given up the practice quite. Poor thing of usages! coerced, compell'd, Victim when wrong, and martyr oft when right, Condemn'd to child-bed, as men for their sins Have shaving too entail'd upon their chins,— A daily plague, which in the aggregate May average on the whole with parturition. But as to women, who can penetrate The real sufferings of their she condition? Man's very sympathy with their estate Has much of selfishness, and more suspicion. Their love, their virtue, beauty, education, But form good housekeepers, to breed a nation. All this were very well, and can't be better; But even this is difficult, Heaven knows, So many troubles from her birth beset her, Such small distinction between friends and foes, The gilding wears so soon from off her fetter, That—but ask any woman if she'd choose (Take her at thirty, that is) to have been Female or male? a schoolboy or a queen? 'Petticoat influence' is a great reproach, Which even those who obey would fain be thought To fly from, as from hungry pikes a roach; But since beneath it upon earth we are brought, By various joltings of life's hackney coach, I for one venerate a petticoat— A garment of a mystical sublimity, No matter whether russet, silk, or dimity. Much I respect, and much I have adored, In my young days, that chaste and goodly veil, Which holds a treasure, like a miser's hoard, And more attracts by all it doth conceal— A golden scabbard on a Damasque sword, A loving letter with a mystic seal, A cure for grief—for what can ever rankle Before a petticoat and peeping ankle? And when upon a silent, sullen day, With a sirocco, for example, blowing, When even the sea looks dim with all its spray, And sulkily the river's ripple 's flowing, And the sky shows that very ancient gray, The sober, sad antithesis to glowing,— 'T is pleasant, if then any thing is pleasant, To catch a glimpse even of a pretty peasant. We left our heroes and our heroines In that fair clime which don't depend on climate, Quite independent of the Zodiac's signs, Though certainly more difficult to rhyme at, Because the sun, and stars, and aught that shines, Mountains, and all we can be most sublime at, Are there oft dull and dreary as a dun— Whether a sky's or tradesman's is all one. An in-door life is less poetical; And out-of-door hath showers, and mists, and sleet, With which I could not brew a pastoral. But be it as it may, a bard must meet All difficulties, whether great or small, To spoil his undertaking or complete, And work away like spirit upon matter, Embarrass'd somewhat both with fire and water.

This poem is in the public domain.

I had a dream, which was not all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars Did wander darkling in the eternal space, Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air; Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day, And men forgot their passions in the dread Of this their desolation; and all hearts Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light: And they did live by watchfires—and the thrones, The palaces of crowned kings—the huts, The habitations of all things which dwell, Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd, And men were gather'd round their blazing homes To look once more into each other's face; Happy were those who dwelt within the eye Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch: A fearful hope was all the world contain'd; Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks Extinguish'd with a crash—and all was black. The brows of men by the despairing light Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits The flashes fell upon them; some lay down And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil'd; And others hurried to and fro, and fed Their funeral piles with fuel, and look'd up With mad disquietude on the dull sky, The pall of a past world; and then again With curses cast them down upon the dust, And gnash'd their teeth and howl'd: the wild birds shriek'd And, terrified, did flutter on the ground, And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl'd And twin'd themselves among the multitude, Hissing, but stingless—they were slain for food. And War, which for a moment was no more, Did glut himself again: a meal was bought With blood, and each sate sullenly apart Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left; All earth was but one thought—and that was death Immediate and inglorious; and the pang Of famine fed upon all entrails—men Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh; The meagre by the meagre were devour'd, Even dogs assail'd their masters, all save one, And he was faithful to a corse, and kept The birds and beasts and famish'd men at bay, Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead Lur'd their lank jaws; himself sought out no food, But with a piteous and perpetual moan, And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand Which answer'd not with a caress—he died. The crowd was famish'd by degrees; but two Of an enormous city did survive, And they were enemies: they met beside The dying embers of an altar-place Where had been heap'd a mass of holy things For an unholy usage; they rak'd up, And shivering scrap'd with their cold skeleton hands The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath Blew for a little life, and made a flame Which was a mockery; then they lifted up Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld Each other's aspects—saw, and shriek'd, and died— Even of their mutual hideousness they died, Unknowing who he was upon whose brow Famine had written Fiend. The world was void, The populous and the powerful was a lump, Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless— A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay. The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still, And nothing stirr'd within their silent depths; Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea, And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp'd They slept on the abyss without a surge— The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave, The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before; The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air, And the clouds perish'd; Darkness had no need Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

This poem is in the public domain.

. . . Unquenched, unquenchable,

Around, within, thy heart shall dwell;

Nor ear can hear nor tongue can tell

The tortures of that inward hell!

But first, on earth as vampire sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

Must feed thy livid living corse:

Thy victims ere they yet expire

Shall know the demon for their sire,

As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

But one that for thy crime must fall,

The youngest, most beloved of all,

Shall bless thee with a father's name —

That word shall wrap thy heart in flame!

Yet must thou end thy task, and mark

Her cheek's last tinge, her eye's last spark,

And the last glassy glance must view

Which freezes o'er its lifeless blue;

Then with unhallowed hand shalt tear

The tresses of her yellow hair,

Of which in life a lock when shorn

Affection's fondest pledge was worn,

But now is borne away by thee,

Memorial of thine agony!

This poem is in the public domain.

Start not—nor deem my spirit fled:

In me behold the only skull

From which, unlike a living head,

Whatever flows is never dull.

I lived, I loved, I quaff'd, like thee:

I died: let earth my bones resign;

Fill up—thou canst not injure me;

The worm hath fouler lips than thine.

Better to hold the sparkling grape,

Than nurse the earth-worm's slimy brood;

And circle in the goblet's shape

The drink of Gods, than reptiles' food.

Where once my wit, perchance, hath shone,

In aid of others' let me shine;

And when, alas! our brains are gone,

What nobler substitute than wine?

Quaff while thou canst—another race,

When thou and thine like me are sped,

May rescue thee from earth's embrace,

And rhyme and revel with the dead.

Why not? since through life's little day

Our heads such sad effects produce;

Redeem'd from worms and wasting clay,

This chance is theirs, to be of use.

First published in American Poetry: A Miscellany (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922)

|

Near this Spot |

When some proud Son of Man returns to Earth,

Unknown to Glory but upheld by Birth,

The sculptor's art exhausts the pomp of woe,

And storied urns record who rests below:

When all is done, upon the Tomb is seen

Not what he was, but what he should have been.

But the poor Dog, in life the firmest friend,

The first to welcome, foremost to defend,

Whose honest heart is still his Master's own,

Who labours, fights, lives, breathes for him alone,

Unhonour'd falls, unnotic'd all his worth,

Deny'd in heaven the Soul he held on earth:

While man, vain insect! hopes to be forgiven,

And claims himself a sole exclusive heaven.

Oh man! thou feeble tenant of an hour,

Debas'd by slavery, or corrupt by power,

Who knows thee well, must quit thee with disgust,

Degraded mass of animated dust!

Thy love is lust, thy friendship all a cheat,

Thy tongue hypocrisy, thy heart deceit!

By nature vile, ennobled but by name,

Each kindred brute might bid thee blush for shame.

Ye! who behold perchance this simple urn,

Pass on, it honors none you wish to mourn.

To mark a friend's remains these stones arise;

I never knew but one—and here he lies.

This poem is in the public domain.

When we two parted

In silence and tears,

Half broken-hearted

To sever for years,

Pale grew thy cheek and cold,

Colder thy kiss;

Truly that hour foretold

Sorrow to this.

The dew of the morning

Sunk chill on my brow—

It felt like the warning

Of what I feel now.

Thy vows are all broken,

And light is thy fame;

I hear thy name spoken,

And share in its shame.

They name thee before me,

A knell to mine ear;

A shudder comes o'er me—

Why wert thou so dear?

They know not I knew thee,

Who knew thee too well—

Long, long shall I rue thee,

Too deeply to tell.

In secret we met—

In silence I grieve,

That thy heart could forget,

Thy spirit deceive.

If I should meet thee

After long years,

How should I greet thee?—

With silence and tears.

This poem is in the public domain.

At midnight in the month of June,

I stand beneath the mystic moon.

An opiate vapour, dewy, dim,

Exhales from out her golden rim,

And, softly dripping, drop by drop,

Upon the quiet mountain top.

Steals drowsily and musically

Into the univeral valley.

The rosemary nods upon the grave;

The lily lolls upon the wave;

Wrapping the fog about its breast,

The ruin moulders into rest;

Looking like Lethe, see! the lake

A conscious slumber seems to take,

And would not, for the world, awake.

All Beauty sleeps!—and lo! where lies

(Her easement open to the skies)

Irene, with her Destinies!

Oh, lady bright! can it be right—

This window open to the night?

The wanton airs, from the tree-top,

Laughingly through the lattice drop—

The bodiless airs, a wizard rout,

Flit through thy chamber in and out,

And wave the curtain canopy

So fitfully—so fearfully—

Above the closed and fringed lid

’Neath which thy slumb’ring sould lies hid,

That o’er the floor and down the wall,

Like ghosts the shadows rise and fall!

Oh, lady dear, hast thous no fear?

Why and what art thou dreaming here?

Sure thou art come p’er far-off seas,

A wonder to these garden trees!

Strange is thy pallor! strange thy dress!

Strange, above all, thy length of tress,

And this all solemn silentness!

The lady sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

Which is enduring, so be deep!

Heaven have her in its sacred keep!

This chamber changed for one more holy,

This bed for one more melancholy,

I pray to God that she may lie

Forever with unopened eye,

While the dim sheeted ghosts go by!

My love, she sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

As it is lasting, so be deep!

Soft may the worms about her creep!

Far in the forest, dim and old,

For her may some tall vault unfold—

Some vault that oft hath flung its black

And winged pannels fluttering back,

Triumphant, o’er the crested palls,

Of her grand family funerals—

Some sepulchre, remote, alone,

Against whose portal she hath thrown,

In childhood, many an idle stone—

Some tomb fromout whose sounding door

She ne’er shall force an echo more,

Thrilling to think, poor child of sin!

It was the dead who groaned within.

This poem is in the public domain.

This poem is in the public domain. Presented here are the prologue and cantos I - XXVII.

Break, break, break,

On thy cold gray stones, O sea!

And I would that my tongue could utter

The thoughts that arise in me.

O, well for the fisherman's boy,

That he shouts with his sister at play!

O, well for the sailor lad,

That he sings in his boat on the bay!

And the stately ships go on

To their haven under the hill;

But O for the touch of a vanished hand,

And the sound of a voice that is still!

Break, break, break,

At the foot of thy crags, O sea!

But the tender grace of a day that is dead

Will never come back to me.

This poem is in the public domain.

To Sleep I give my powers away;

My will is bondsman to the dark;

I sit within a helmless bark,

And with my heart I muse and say:

O heart, how fares it with thee now,

That thou should fail from thy desire,

Who scarcely darest to inquire,

"What is it makes me beat so low?"

Something it is which thou hast lost,

Some pleasure from thine early years.

Break thou deep vase of chilling tears,

That grief hath shaken into frost!

Such clouds of nameless trouble cross

All night below the darkened eyes;

With morning wakes the will, and cries,

"Thou shalt not be the fool of loss."

This poem is in the public domain.

Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean,

Tears from the depth of some divine despair

Rise in the heart, and gather to the eyes,

In looking on the happy autumn-fields,

And thinking of the days that are no more.

Fresh as the first beam glittering on a sail,

That brings our friends up from the underworld,

Sad as the last which reddens over one

That sinks with all we love below the verge;

So sad, so fresh, the days that are no more.

Ah, sad and strange as in dark summer dawns

The earliest pipe of half-awakened birds

To dying ears, when unto dying eyes

The casement slowly grows a glimmering square;

So sad, so strange, the days that are no more.

Dear as remembered kisses after death,

And sweet as those by hopeless fancy feigned

On lips that are for others; deep as love,

Deep as first love, and wild with all regret;

O Death in Life, the days that are no more!

This poem is in the public domain.

And death shall have no dominion.

Dead men naked they shall be one

With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;

Though lovers be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.

And death shall have no dominion.

Under the windings of the sea

They lying long shall not die windily;

Twisting on racks when sinews give way,

Strapped to a wheel, yet they shall not break;

Faith in their hands shall snap in two,

And the unicorn evils run them through;

Split all ends up they shan't crack;

And death shall have no dominion.

And death shall have no dominion.

No more may gulls cry at their ears

Or waves break loud on the seashores;

Where blew a flower may a flower no more

Lift its head to the blows of the rain;

Though they be mad and dead as nails,

Heads of the characters hammer through daisies;

Break in the sun till the sun breaks down,

And death shall have no dominion.

from The Poems of Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1943 by New Directions Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

from The Poems of Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1939 by New Directions Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

Even the bravest that are slain

Shall not dissemble their surprise

On waking to find valor reign,

Even as on earth, in paradise;

And where they sought without the sword

Wide field of asphodel fore’er,

To find that the utmost reward

Of daring should be still to dare.

The light of heaven falls whole and white

And is not shattered into dyes,

The light for ever is morning light;

The hills are verdured pasture-wise;

The angel hosts with freshness go,

And seek with laughter what to brave;—

And binding all is the hushed snow

Of the far-distant breaking wave.

And from a cliff-top is proclaimed

The gathering of the souls for birth,

The trial by existence named,

The obscuration upon earth.

And the slant spirits trooping by

In streams and cross- and counter-streams

Can but give ear to that sweet cry

For its suggestion of what dreams!

And the more loitering are turned

To view once more the sacrifice

Of those who for some good discerned

Will gladly give up paradise.

And a white shimmering concourse rolls

Toward the throne to witness there

The speeding of devoted souls

Which God makes his especial care.

And none are taken but who will,

Having first heard the life read out

That opens earthward, good and ill,

Beyond the shadow of a doubt;

And very beautifully God limns,

And tenderly, life’s little dream,

But naught extenuates or dims,

Setting the thing that is supreme.

Nor is there wanting in the press

Some spirit to stand simply forth,

Heroic in its nakedness,

Against the uttermost of earth.

The tale of earth’s unhonored things

Sounds nobler there than ’neath the sun;

And the mind whirls and the heart sings,

And a shout greets the daring one.

But always God speaks at the end:

‘One thought in agony of strife

The bravest would have by for friend,

The memory that he chose the life;

But the pure fate to which you go

Admits no memory of choice,

Or the woe were not earthly woe

To which you give the assenting voice.’

And so the choice must be again,

But the last choice is still the same;

And the awe passes wonder then,

And a hush falls for all acclaim.

And God has taken a flower of gold

And broken it, and used therefrom

The mystic link to bind and hold

Spirit to matter till death come.

’Tis of the essence of life here,

Though we choose greatly, still to lack

The lasting memory at all clear,

That life has for us on the wrack

Nothing but what we somehow chose;

Thus are we wholly stripped of pride

In the pain that has but one close,

Bearing it crushed and mystified.

This poem is in the public domain.

Time drops in decay,

Like a candle burnt out,

And the mountains and the woods

Have their day, have their day;

What one in the rout

Of the fire-born moods

Has fallen away?

| About this poem: Literary scholar Richard Ellman writes in The Identity of Yeats that "Moods...are conspicuously, but not exclusively, emotional or temperamental; they differ from emotions in having form and, often, intellectual structure. Less fleeting than a mere wish, and less crystallized than a belief, a mood is suspended between fluidity and solidity. It can be tested only by the likelihood of its being experienced at all, and being so, by many people." |

This poem appeared in Poem-A-Day on February 17, 2013. Browse the Poem-A-Day archive. This poem is in the public domain.

Hands, do what you’re bid:

Bring the balloon of the mind

That bellies and drags in the wind

Into its narrow shed.

This poem is in the public domain.

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

This poem is in the public domain.

A wind comes from the north

Blowing little flocks of birds

Like spray across the town,

And a train, roaring forth,

Rushes stampeding down

With cries and flying curds

Of steam, out of the darkening north.

Whither I turn and set

Like a needle steadfastly,

Waiting ever to get

The news that she is free;

But ever fixed, as yet,

To the lode of her agony.

This poem is in the public domain.

This poem is in the Public Domain.

why must itself up every of a park

anus stick some quote statue unquote to

prove that a hero equals any jerk

who was afraid to dare to answer "no"?

quote citizens unquote might otherwise

forget(to err is human;to forgive

divine)that if the quote state unquote says

"kill" killing is an act of christian love.

"Nothing" in 1944 AD

"can stand against the argument of mil

itary necessity"(generalissimo e)

and echo answers "there is no appeal

from reason"(freud)—you pays your money and

you doesn't take your choice. Ain't freedom grand

From Complete Poems: 1904-1962 by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage. Used with the permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation. Copyright © 1923, 1931, 1935, 1940, 1951, 1959, 1963, 1968, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Copyright © 1976, 1978, 1979 by George James Firmage.

I will wade out

till my thighs are steeped in burn-

ing flowers

I will take the sun in my mouth

and leap into the ripe air

Alive

with closed eyes

to dash against darkness

in the sleeping curves of my

body

Shall enter fingers of smooth mastery

with chasteness of sea-girls

Will I complete the mystery

of my flesh

I will rise

After a thousand years

lipping

flowers

And set my teeth in the silver of the moon

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on October 14, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets.

A Christmas circular letter The city had withdrawn into itself And left at last the country to the country; When between whirls of snow not come to lie And whirls of foliage not yet laid, there drove A stranger to our yard, who looked the city, Yet did in country fashion in that there He sat and waited till he drew us out, A-buttoning coats, to ask him who he was. He proved to be the city come again To look for something it had left behind And could not do without and keep its Christmas. He asked if I would sell my Christmas trees; My woods—the young fir balsams like a place Where houses all are churches and have spires. I hadn't thought of them as Christmas trees. I doubt if I was tempted for a moment To sell them off their feet to go in cars And leave the slope behind the house all bare, Where the sun shines now no warmer than the moon. I'd hate to have them know it if I was. Yet more I'd hate to hold my trees, except As others hold theirs or refuse for them, Beyond the time of profitable growth— The trial by market everything must come to. I dallied so much with the thought of selling. Then whether from mistaken courtesy And fear of seeming short of speech, or whether From hope of hearing good of what was mine, I said, "There aren't enough to be worth while." "I could soon tell how many they would cut, You let me look them over." "You could look. But don't expect I'm going to let you have them." Pasture they spring in, some in clumps too close That lop each other of boughs, but not a few Quite solitary and having equal boughs All round and round. The latter he nodded "Yes" to, Or paused to say beneath some lovelier one, With a buyer's moderation, "That would do." I thought so too, but wasn't there to say so. We climbed the pasture on the south, crossed over, And came down on the north. He said, "A thousand." "A thousand Christmas trees!—at what apiece?" He felt some need of softening that to me: "A thousand trees would come to thirty dollars." Then I was certain I had never meant To let him have them. Never show surprise! But thirty dollars seemed so small beside The extent of pasture I should strip, three cents (For that was all they figured out apiece)— Three cents so small beside the dollar friends I should be writing to within the hour Would pay in cities for good trees like those, Regular vestry-trees whole Sunday Schools Could hang enough on to pick off enough. A thousand Christmas trees I didn't know I had! Worth three cents more to give away than sell, As may be shown by a simple calculation. Too bad I couldn't lay one in a letter. I can't help wishing I could send you one, In wishing you herewith a Merry Christmas.

From Mountain Interval

Fly envious Time, till thou run out thy race, Call on the lazy leaden-stepping hours, Whose speed is but the heavy Plummets pace; And glut thy self with what thy womb devours, Which is no more then what is false and vain, And meerly mortal dross; So little is our loss, So little is thy gain. For when as each thing bad thou hast entomb'd, And last of all, thy greedy self consum'd, Then long Eternity shall greet our bliss With an individual kiss; And Joy shall overtake us as a flood, When every thing that is sincerely good And perfectly divine, With Truth, and Peace, and Love shall ever shine About the supreme Throne Of him, t'whose happy-making sight alone, When once our heav'nly-guided soul shall clime, Then all this Earthy grosnes quit, Attir'd with Stars, we shall for ever sit, Triumphing over Death, and Chance, and thee O Time.

This poem is in the public domain.

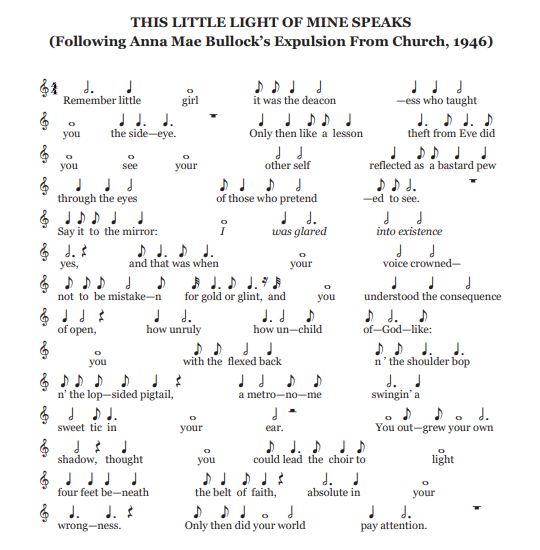

Copyright © 2020 by Crystal Valentine. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on July 24, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

I too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond all this fiddle.

Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers that there is in

it after all, a place for the genuine.

Hands that can grasp, eyes

that can dilate, hair that can rise

if it must, these things are important not because a

high-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because they are

useful; when they become so derivative as to become unintelligible, the

same thing may be said for all of us—that we

do not admire what

we cannot understand. The bat,

holding on upside down or in quest of something to

eat, elephants pushing, a wild horse taking a roll, a tireless wolf under

a tree, the immovable critic twinkling his skin like a horse that feels a flea, the base—

ball fan, the statistician—case after case

could be cited did

one wish it; nor is it valid

to discriminate against “business documents and

school-books”; all these phenomena are important. One must make a distinction

however: when dragged into prominence by half poets, the result is not poetry,

nor till the autocrats among us can be

“literalists of

the imagination”—above

insolence and triviality and can present

for inspection, imaginary gardens with real toads in them, shall we have

it. In the meantime, if you demand on the one hand, in defiance of their opinion—

the raw material of poetry in

all its rawness, and

that which is on the other hand,

genuine, then you are interested in poetry.

From Others for 1919: An Anthology of the New Verse (Nicholas L. Brown, 1920), edited by Alfred Kreymborg. This poem is in the public domain.