mobileMenu

- Poems

- Poets

- Poem-a-Day

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

User account menu

Books Noted 2017

Page submenu block

Graywolf Press, August 2017

Coldly beautiful and relentlessly quotable, this eighth collection from Mary Jo Bang (who won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Elegy, published by Graywolf Press in 2007) is also her first to consist wholly of prose poems, and her second, after The Eye Like a Strange Balloon (Grove Press, 2004), to take its bearings from modern art. Many of its pages respond to the life and work of Lucia Moholy, the photographer whose Bauhaus-era images were later used without her consent. Looking back at us “like someone looking into a box of scattered catastrophes,” Moholy may be one type of the neglected artist, or the woman kept down by patriarchy; other characters, silhouettes, and imagined faces surface amid Bang’s bleak, almost Beckett-like aphorisms and terse exclamations.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, August 2017

Frank Bidart remains one of the very rare poets whose work attracts plaudits from highbrow critics while carrying—not occasionally but always—raw, painful, violent emotional weight. He’s been in that position since the 1970s, when his early work outlined his troubled parents and childhood in Bakersfield, California: “Everything I’ve written,” he says in one of several interviews in this volume, “has been an argument with the world I’m from.” Bidart became known for narrative poems in the voice of historical characters—a serial killer (“Herbert White”), a lovesick composer (Hector Berlioz), a murderous sculptor (Benvenuto Cellini). In the 2000s, he bloomed into a great poet of abstract, compact lyrics: public and political (“Curse,” about 9/11), or familial and elegiac, or homoerotic, or all three at once (“How you hurtled yourself against, how // cunningly you / failed to elude love”).

Milkweed Editions, September 2017

Opioids have left trails of disaster across America, but few places have been hit harder than West Virginia, few communities harder than rural white ones. William Brewer’s pitch-perfect, tightly focused first full-length collection builds on his chapbook Oxyana (Poetry Society of America, 2016), named for the town of Oceana, whose new nickname comes from its opioid casualties. Brewer displays concision alongside journalistic skills, demonstrating how the rise in addiction matches declines in hope, and in employment (in this town, it’s glassblowing, which gives Brewer further ironies). More often, though, he gets personal and makes us see one figure’s hardships: in “Naloxone” (named for the drug that treats ODs), “All the things / I meant to do are burnt spoons // hanging from the porch like chimes.” Opioid dependency, in “To the Addict Who Mugged Me,” is “[a] never-ending dial tone / chewing the receptors in your brain.”

Wave Books, April 2017

Brolaski has a strong musical ear, and the poems in this collection feature various rhythmic voices, blending the idiomatic expressions of text messages with the tropes of both rap and Chaucer while addressing the subjects of gender and race. At times the poems read like manifestos, fueled by a robust gusto, but nothing too certain is manifest. Brolaski excels at the sensual: “Suddenly you and your neighbors thighs are pressed together, accidental camaraderie or blunt eroticism. And neither of you move away.” There are many references to popular culture, as in “Melancholy Lake,” a dream poem featuring Brad Pitt, as well as one poem that includes a Hank Williams lyric and another a quote from the Wu-Tang Clan.

Alice James Books, October 2017

The ambitious and heartfelt second volume from Jennifer Chang gives many kinds of readers many ways in. At its start it’s an almost mystical collection of rural and nature-based poems, its earnest registers reminiscent of Galway Kinnell: “Were I more horse than rider,” Chang muses, “I would better understand the beast I am.” Deer, dogs, and flower names figure largely too. Soon, though, Chang’s modern America emerges from her dense pastures and her wild woods: we discover Ohio and New Jersey (“the good smell / of the garden state, the cracked snail shells // baking on an off-white shore”). After that Chang redescribes herself—just as fiercely, and with much more specificity—as a D.C.-based parent, alert to the national capital’s neighborhoods, its aches and quirks: “This is the safest route // to the closest Metro stop."

Copper Canyon Press, November 2017

Those amused, or shocked, by Victoria Chang’s The Boss (McSweeney’s, 2013)—an almost giddily unified book in which every poem used metaphors from an oppressive workplace—should like Chang’s new work. But they won’t be the only ones—and not even they will expect Chang’s grander scope, her greater nuance, and her more generous attention to its characters’ adult lives. Chang’s “Barbie,” the protagonist for most of the poems (“Barbie Chang Got Her Hair Done,” “Barbie Chang’s Mother Calls”) is a suburban Chinese American mom who does everything right and still feels she has failed.

BOA Editions, April 2017

The jubilantly titled debut from Chen Chen weaves together his complex narrative as an immigrant and a queer man. The poems are full of wisdom and wit, engaging with the slow revelation of the poet’s sense of self but also with metaphysics, psychology, and the cosmos: “Your smile in the early dark is a paraphrase of Mars. Your smile in the deep dark is an anagram of Jupiter.” “In the City” is an accomplished poem in which the speaker and his mother make dumplings and are interrupted by his father. It utilizes fractured poetics next to the fractured speech of immigrant parents. There are also poems about nature, sex, and loss, and a poem echoing Christopher Smart’s ode to his cat, “For I will consider my boyfriend Jeffrey. / For he is an atheist but makes room for the unseen, unsayable.”

Wave Books, September 2017

CAConrad is known in some quarters—and rightly so—for “(Soma)tic poetry rituals,” physical, social, and mental exercises—somewhere between yoga and performance art—that lead Conrad, and might lead you, to compose new poems. Like some of Conrad’s other collections—but starkly with more tragic overtones—this one mixes prose about the rituals and their occasions with the sets of poems that follow from them. What emerges begins in heartbreak and elegy, with the death of Conrad’s partner Earth—probably in a homophobic hate crime—during the 1990s. Soon enough, in poems as in rituals (which involve eating crystals, blowing bubbles, or mapping ants’ paths), Conrad conceives of Utopian affirmations, rejecting existing human institutions (meat-eating, patriarchy, war) in favor of a newly wild flourishing.

Anhinga Press, September 2017

This debut from HAUNTIE (the nom de plume of the Hmong American writer May Yang) puts its performance of outrage at center stage and justifies its stances thoroughly too. At once a revenger, a ghost, and an auntie, helping younger women kept down by powerful men, Yang’s HAUNTIE persona attacks patriarchy and racism in very general terms. “[T]his heat which scorched my father’s spirit down / will look onto you and take you like it took me too,” she writes; “[I] can be silent, no more! // to this white lie // or give me death.”

Coffee House Press, October 2017

Victor Hernández Cruz began his celebrated career in the 1970s in Puerto Rican New York City; he now resides in Morocco, and his latest assembly of poems and prose—exuberant, spontaneous, fast-paced—looks back over several seas and centuries at the broad gauge of Caribbean history, finding “wonder, mystery, possibilities, imagination” as well as injustice, untold tales, and “the pull of the sea.” Cruz sees himself as a “child mountain....counting the tamarindo / Coconut lollipops,” recalls his “Lower East Side world now lost forever,” and traces the Afro-Atlantic lineage of his favorite music, “the Mama drums tumba / the gawana gimba base guitar…sunken in poly-rhythms.”

Omnidawn, April 2017

Rayfish is a book of poetic meditations that vacillate between long prose poems and short lyrical essays. The book’s epigraph describes art as evoking a mutual response in the space between the work and the viewer, which is a central theme in Hickman’s work. The book’s title comes from the painter Soutine’s passion for making still-life paintings of various meat, including the ray, a flat fish that appears to fly like a bird through water. In the second poem, both the painter and the fish appear: “Soutine attempts to keep the color of his first carcasses fresh with buckets of blood.”

W. W. Norton, March 2017

Magdalene is Marie Howe’s fourth book of poems, What the Living Do being the book for which she is most well known. There are several key characters in Howe’s work: child, teacher, and father. In this book the central events are the revelation of love after adopting a daughter later in life and a teacher’s deep presence (though thronged with other disciples). There are great progressions of thought through Howe’s poems through the years. In What the Living Do the first poem ends with: “I was the girl. What happened taught me to follow him, whoever he was, / calling and calling his name.” In the new book a poem asks, “Who would / follow that young woman down the narrow hallway? / Who would call her name until she turns?”

Sarabande Books, February 2017

Johnson’s first book of poems takes on subject matter such as growing up queer in America and how politicized the queer female body is. Her imagery is sharp, and she consistently brings us into liminal and charged spaces, like when she is a flower girl holding up a wedding ceremony with her attention to the petals and their distribution. In “Gay Marriage Poem” the speaker takes us to an imaginary edge, ending with: “Of such loves unwrit, at the boundary layer / between earth and air, / I feel most clear.” References to Rilke and Hopkins appear in these poems, as well as pop culture luminaries like Cyndi Lauper and Patti Smith.

Alice James Books, September 2017

“I am black alive and looking back at you,” June Jordan announced in 1969. She kept looking, and protesting, and advocating, and clarifying her life, and setting examples for radical activists, until her death in 2002. This first posthumous volume to hold both her verse and her prose puts her back near the center of conversations where—with Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich—she clearly belongs. It takes in bold verse devoted to causes personal and international; brief segments from her novel for young people, His Own Where (Feminist Press, 1971) and from Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood (Basic Civitas Books, 2000); collaborations for singers and for the stage; and a panoply of speeches and essays, including her famous defenses of black English, an homage to Walt Whitman’s “democratic faith,” and a profile of “Phillis Miracle Wheatley.”

Copper Canyon Press, July 2017

Vivid, insightful, and sometimes angry, Kasischke’s voice is great company for the reader. “The Cause of All My Suffering” is a radiant self-portrait of the darkness, the place in us where we are furious over disappointment, where we have rage and no longer care if we sort it out correctly. In the poem the speaker detests the neighbors’ rescued indoor piglets. She sees the piglets and their savior as common, ubiquitous, and grotesque. “Horrible life!” Then Kasischke sneaks in the notion “I pray // to God to give me / the ability to write // better poems than the poems of those / whom I despise.”

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 2017

A few weeks before Knott died in 2014, he self-published his Collected Poetry 1960–2014 through Amazon, including nearly a thousand poems from which the poet Thomas Lux has chosen 152 for this volume. Knott had a difficult early life. His mother died in childbirth when he was six, and four years later his father killed himself. He was in an orphanage for years and spent a year in a mental hospital. The poems that speak directly to those facts are striking, such as “Christmas at the Orphanage,” the scouring “The Day After My Father’s Death” and the “The Closet.”

Penguin, March 2017

Map to the Stars is about both kinds of star maps, ostensibly the celestial but also that of celebrities. The chief star in the book is the speaker’s father, and the heavens are encountered through Star Trek, Star Wars, and the return of a space shuttle to Earth. Matejka’s is a very human astronomy. The poem “Blacks Swinging Low” begins, “My black father’s absent jurisdiction / includes this city of skin I’m in. …Praying / to go to orbit, in a space shuttle // where everyone looks the same / in a space suit.” Many poems report from the speaker’s childhood in the 1980s. It is in 1981 that the speaker sends away for a solar system model, with “five wrinkled bills,” and the model never comes.

Ecco, September 2017

Nicole Sealey’s debut feels like a debut, in the best sense: a clever poet with a lot to say will try everything once, or more than once, in order to see what works, from centos, to poems that critique her own earlier poems (“In Defense of ‘Candelabra with Heads’”), to a sestina in which all six end-words are some form of “pit”—“Pity,” “pulpit,” “Eliot Spitzer”) to straightforward first-person reactions, as in one poem set in Nigeria: “The West in me wants the mansion / to last. The African knows it cannot.” Sealey’s repertoire of devices might link her to Paul Muldoon, or to Kathleen Ossip, whose tricky relation to memoir and to public trauma she also shares.

Graywolf Press, September 2017

Danez Smith has become one of a generation’s most noticed poets, and for good reason: at once a stunning performer and a tersely effective arranger of words on the page, Smith can address the Black Lives Matter movement, the erasure of black humanity by malign police, and then pivot to vivid, sexy, or scary records from a complex queer sexuality. What held for Smith’s debut [insert] boy (YesYes Books, 2014) still holds for this longer second effort, whose most quotable poems address murderous institutional racism: “dear white america….i can’t stand your ground.” Much of the collection responds, in addition, to Smith’s diagnosis with HIV. “[I’m] not the kind of black man who dies on the news,” Smith muses. “[I’m] the kind who grows thinner & thinner & thinner.”

Graywolf Press, March 2017

The first and larger half of Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS is made up of seventeen individual poems, the second is one long poem titled “Whereas,” which responds to President Obama’s 2009 congressional resolution of apology to Native Americans. The poems in the first half are set on the page in ways that complicate or slow down reading, such as a thin stripe of a poem with many words hyphenated from one line to the next. Long Soldier is inventive in her uses of typography, poems in shapes, crossed-out lines, and boxed text. Throughout the book Long Soldier addresses the struggle of coming of age as a member of the Oglala Sioux tribe in America. Some of the poems experiment with language, while others tell stories—the speaker being teased with schoolyard “warcry” taunts or being shocked by a woman’s admission that she hadn’t imagined Natives could feel.

Persea Books, February 2017

As its more common negative form “anorexia” hints, “orexia” means appetite and desire. Spaar’s new book addresses dread, as well as weariness and age, but in the end sides with love of life and delight. The verbiage in Orexia vibrates like a bass fiddle and surprises the reader, as in the poem “Temple Tomb”: “Then the changes: // placental, myrrhed. Wet hem / when you appeared. // What did your body ever have / to do with me? In my astonished mouth, // enskulled jawbone guessed, / though as yet I didn’t know you.” Spaar’s trickery and mastery of language is on full display, making the word placenta an adjective instead of a noun and using the word myrrh as a verb.

W. W. Norton, April 2017

In his new book the celebrated poet Gerald Stern tells us how he got started: by keeping a twenty under his insole, “I say it’s just / in case I say it’s for an emergency,” and also revealing to the reader how he still does this today and noting that a twenty wouldn’t buy much now “not nearly enough / for a straw hat to cover my sunspots.” Stern often seems to be telling a story that feels urgent and real, while also trailing off elsewhere and finishing in a private code. Much of Galaxy Love’s subject matter is about having lived a long time. Across the book there are numbers everywhere: “sixty years later,” “seventy-six years ago,” “now thirty years since,” “after seventy years.”

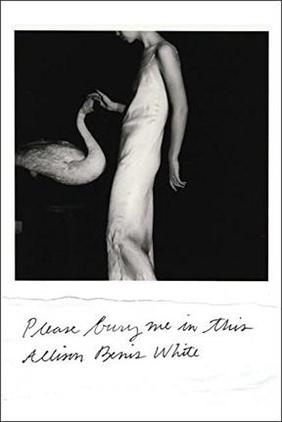

Four Way Books, March 2017

White’s new collection is made up of short, untitled poems. There are images that manage to be ethereal and exotic in addition to being physical and domestic. For example, “In the living room once, white balloons twisted into the ghosts of animals,” and in another poem, “I remember the paper house, hung from a cage hook in my room, swaying.” The title of the book was found as a note pinned to a dress in a friend’s closet. The book is dedicated to the author’s father and also to “the four women I knew who took their lives within a year.” White is in dialogue with letters and the epistolary form, using phrases such as “I am writing you this letter,” “This is a love letter,” and in the book’s fifth poem, a long list of addressed subjects follow: “Dear Kitty, Dear God, Dear Lucifer. // I cut my hair off this morning, placed the long blond braid in an envelope. // There is only one arc: suffering, transformation. // Dear Linda, Sexton wrote to her daughter on a flight to St. Louis, I love you. // In other words, these words, their spectacular lack.”

Mariner Books, September 2017

The Michigan-based Marcus Wicker’s second collection, after Maybe the Saddest Thing (Harper Perennial, 2012), might at first seem to place him comfortably—and proudly—in a register cocreated by Terrance Hayes. Wicker makes witty yet serious, encyclopedically allusive work whose excitable energies and wide range of diction belie the gravity of their topics: structural injustice, familial loyalty, uneasy adulthood, and institutional racism. “I come from a long braid of dangerous men // who learned to talk their way out of small compartments,” Wicker announces. “I’m a real good schmoozer but it kills me inside.” An especially spiky page projects “the white ball caught in the throat / of my granddaddy’s Negro League catcher’s mitt.”