For as long as there have been writers, there have been texts that have been challenged, censored, burned, and banned. The stories of banned literature do not just belong in the history books; even today, some of the most influential texts in our bookstores and libraries are currently being challenged or have been challenged at some point before. Here we take a look at fifteen significant poems, poetry collections, and poets that have been censored and banned throughout history. Find out more about these books and others during Banned Books Week, October 5-October 11, 2025.

Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), Charles Baudelaire

Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), Charles Baudelaire

As soon as Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal was published in June of 1857, thirteen of its 100 poems were arraigned for inappropriate content. On August 20, 1857, French lawyer Ernest Pinard, who had also famously prosecuted French author Gustave Flaubert, prosecuted Baudelaire for the collection.

The court banned six of the erotic poems: “Lesbos,” “Femmes damnés,” Le Léthé,” “À celle qui est trop gaie,” “Les Bijoux,” and “Les Métamorphoses du Vampire.” The offensiveness of the texts, the court held, lay not only in their context, but also in their “realism.” According to the judges, the poems “necessarily lead to the excitement of the senses by a crude realism offensive to public decency.”

Baudelaire was charged with a fine of 300 (later reduced to 50) francs, and Les Fleurs du mal suffered from the controversy, becoming known only as a depraved, pornographic work.

In 1861, a second, enlarged edition of Les Fleurs du mal was published, but the six banned poems would not be republished again until Baudelaire's 1866 collection Les Épaves, published in Belgium. The official ban on the poems was not revoked until 1949.

“We Real Cool,” Gwendolyn Brooks

One of Gwendolyn Brooks’s most famous poems, “We Real Cool,” was banned in schools in Mississippi and West Virginia in the 1970s for the penultimate sentence in the poem: “We / Jazz June.” The school districts banned the poem for the supposed sexual connotations of the word “jazz.”

However, Brooks herself maintained that that interpretation was erroneous. As she was quoted as saying in Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks (University Press of Mississippi, 2003): “I didn’t mean that at all. I meant that these young men would have wanted to challenge anything that was accepted by ‘proper’ people, so I thought of something that is accepted by almost everybody, and that is summertime, the month of June. So these pool players, instead of paying the customary respect to the loveliness of June—the flowers, blue sky, honeyed weather—wanted instead to derange it, to scratch their hands in it as if it were a head of hair. This is what went through my head; that is what I meant.

“However, a space can be permitted for a sexual interpretation. Talking about different interpretations gives me a chance to say something I firmly believe—that poetry is for personal use. When you read a poem, you may not get out of it all that the poet put into it, but you are different from the poet. You’re different from everybody else who is going to read the poem, so you should take from it what you need. Use it personally.”

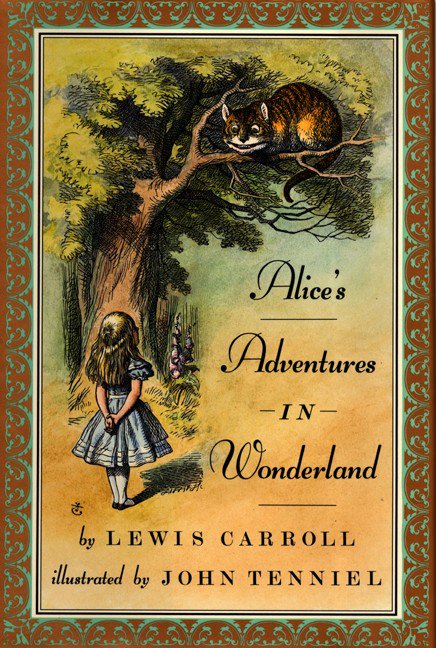

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Though many are familiar with the poems and fantastical story of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, perhaps not as well known is the book’s history of censorship. The book has been challenged and banned several times since its publication in 1865, largely due to its alleged promotion of drug use. In the book, Alice encounters a caterpillar who sits on top of a mushroom smoking hookah. Alice herself becomes exposed to psychedelic, mind- and body-altering experiences, in which she grows and shrinks in size (undoubtedly inspired by Carroll’s own experiences with a rare neurological disorder that causes hallucinations and affects the sufferer’s perception of size—later named Alice in Wonderland Syndrome).

However, it was not the drug references but the talking animals that ultimately got Carroll banned in China in 1931. Though characters like the Cheshire Cat and the White Rabbit remain amongst the most popular in Carroll’s Wonderland novels, General Ho Chien, the governor of Hunan province, deemed it offensive that animals were anthropomorphized and placed on the same level as humans.

Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

In the late 1300s, Geoffrey Chaucer, considered the “father of English literature,” wrote Canterbury Tales, a humorous and critical examination of twenty-nine archetypal characters of late medieval English society. The text drew immediate criticism due to its critical look at the medieval church, as well as its obscene language and sexual innuendos, the latter of which remained a point of contention even centuries later.

In 1873, Anthony Comstock, founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, achieved a federal bill that banned the mailing of “every obscene, lewd, lascivious or filthy book, pamphlet, picture, paper, letter writing, print or other publication of an indecent character.” The Comstock Act, officially known as the Federal Anti-Obscenity Act, banned many world classics, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, for its sexual content.

Though he was widely considered the Palestinian national poet, Mahmoud Darwish frequently faced controversy and censorship with his work. As a young man, Darwish faced house arrest and imprisonment for his activism. He later became increasingly involved in politics, openly criticizing Arab governments and Palestinian politicians. He lived in exile from his homeland for twenty-six years, until he was able to return in 1996.

In 2000, Yossi Sarid, then the education minister of Israel, suggested including works by Darwish in the school curriculum. But right-wing members of President Ehud Barak’s government threatened to introduce a motion of no-confidence. Barak said Israel was “not ready” to teach Darwish in the schools. After Darwish had learned of the controversy, he said, “It is difficult to believe that the most militarily powerful country in the Middle East is threatened by a poem.”

The issue of Darwish’s censorship came up again in 2014, when his works were removed from a major book fair in Saudi Arabia for containing “blasphemous passages.”

In the mid-1950s, Allen Ginsberg began writing “Strophes,” which he later renamed “Howl,” based on a peyote-inspired vision he had of the ancient Phoenician god Moloch. On October 7, 1955, Ginsberg publicly read part of “Howl” for the first time at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, to the praise and acclaim of his fellow Beat writers. The following day, City Lights publisher and poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti sent Ginsberg a telegram asking for the manuscript of the poem. Anticipating a controversial release, before City Lights published the manuscript, Ferlinghetti asked the American Civil Liberties Union if it would defend the book in court if he were prosecuted.

Howl and Other Poems was then published on November 1, 1956, as part of the City Lights Pocket Poets Series. With its long, winding lines; profane language; and frank, racy content about drug use and sexuality, Howl was deemed obscene and Ferlinghetti was arrested and taken to court.

In the case of People of California v. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, on October 3, 1957, Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that Ferlinghetti was not guilty. The defense included reviews praising the collection and the analysis of nine literary experts, all of whom agreed that the work had “literary merit, that it represented a sincere effort by the author to present a social picture, and that the language used was relevant to the theme.”

Considered Turkey’s greatest modern poet, acclaimed both nationally and internationally for his works, Nazim Hikmet was a Communist who was stripped of his citizenship for his political views. His work, which praised his country and the common man, was deemed “subversive” and banned in Turkey from 1938 to 1965.

Hikmet himself spent several years in Turkish prisons and in exile. He wrote many of his most popular poems during these times, such as his masterpiece Human Landscapes from My Country, which he wrote while imprisoned from 1938 to 1950.

Despite the controversy surrounding his works, Hikmet’s poems won the praise and support of artists from all over the world, including Vladimir Mayakovsky, Pablo Neruda, Pablo Picasso, and Jean-Paul Sartre. Now Hikmet’s work is available in more than fifty languages, and he is praised as a major figure in modern poetry.

D. H. Lawrence was no stranger to censorship; his novels Lady Chatterley’s Lover and The Rainbow were censored and banned. However, many of Lawrence’s poems came under fire as well. His poems—such as "All of Us," a sequence of thirty-one war poems—attacked politicians and criticized World War I and imperial policy, but the censorship and editing of the series ultimately rendered the works unreadable.

Lawrence, who wrote poetry from 1905 until his death in 1930, struggled to get his poems into print, especially after the controversy surrounding his other published works of the time. It wasn’t until decades later that Lawrence’s works began to be published in their entirety.

Federico García Lorca is one of the most important Spanish poets and dramatists of the twentieth century, the author of such celebrated works as Romancero Gitano (The Gypsy Ballads), which was reprinted seven times during his lifetime. But his work was still the object of censorship in Spain in the early 1900s. Lorca was openly homosexual and known for his outspoken socialist views, and his works were deemed dangerous for their sexual content, language, and political underpinnings.

In 1936, Lorca was shot to death by Spanish nationalists due to his support of the deposed Republican government. Lorca’s work was burned in Granada’s Plaza del Carmen and banned from Francisco Franco’s Spain. His books remained censored until Franco’s death in 1975.

Amores (Loves) & Ars amatoria (Art of Love), Ovid

Amores (Loves) & Ars amatoria (Art of Love), Ovid

Ovid, best known for his epic poem Metamorphoses, also considered himself a “teacher of love,” so at the end of the first century BC, he wrote Ars amatoria, a guide to love and courtship for his Roman contemporaries. The poem is split into three books; the first two books instruct men how to meet, seduce, and keep a woman, and the third gives comparable advice to women. In 8 AD Caesar Augustus banished Ovid to Tomis on the charge of what Ovid describes as “a poem and a mistake.” The poem in question may very well have been the risqué work, but some believe it may have been Metamorphoses.

In 1497, Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican monk living in Florence, Italy, began burning all objects he found immoral and corruptive in what would be called the Burning of the Vanities. All of Ovid’s works were included in the pyre.

Ovid’s works were challenged again a century later in Elizabethan England as Amores, elegiac poems in a set of three books that describe one of Ovid’s affairs, was proscribed in the 1599 Bishops’ Ban. Ordered by John Whitgift, the archbishop of Canterbury, and Richard Bancroft, the bishop of London, the Bishops’ Ban resulted into the cessation of the printing of questionable books and the destruction of existing copies of those texts. Christopher Marlowe’s translation of the Amores was included in the ban.

More recently, Ars amatoria was one of the books proscribed in the American Library Association catalogue in 1904, and the U.S. Customs Service banned the import of Ars amatoria as late as 1930.

Various Plays by William Shakespeare

Although undoubtedly a stalwart of English literature, Shakespeare has not been immune to various standards of censorship and banning. The Bard’s words have not all been music to the ears of some people, who have had classics like Hamlet, Macbeth, and King Lear withdrawn from school reading lists because of the obscenities, as well as the references to sex and violence. These references were not the full extent of the criticism Shakespeare’s plays have gotten from censors over the years; in the early 1800s, dialogue that in any way incriminated the monarchy or members of the clergy, as well as scenes that addressed differences in social classes, was considered risqué and in bad taste.

Thomas Bowdler was the first to censor Shakespeare’s works on a grand scale. In 1807, Bowdler published the first edition of Family Shakespeare, which included a version of Hamlet with large chunks of dialogue cut out. Bowdler and his sister, Harriet Bowdler, had removed what they considered profanities, obscenities, and indecencies that they believed detracted from the “genius” of the work. Bowdler wrote that nothing “can afford an excuse for profaneness or obscenity; and if these could be obliterated, the transcendent genius of the poet would undoubtedly shine with more unclouded luster.”

While censorship of Shakespeare’s plays certainly occurred in the past, the practice is hardly ancient history. The problematic The Merchant of Venice was banned in the 1930s in schools in Buffalo and Manchester, New York, for its anti-Semitism, but in 1949, a lower court in New York refused to uphold the ban. Still, the issue arose again in 1980, when the play was banned in schools in Midland, Michigan.

In 1996, a school in New Hampshire banned Twelfth Night—in which a young woman disguises herself as a man and attracts a countess—under the school board’s Prohibition of Alternative Lifestyle Instruction Act for allegedly promoting an alternative lifestyle that isn’t good for children to learn about.

More recently, in 2011, according to Arizona state law A.R.S.-15-112, The Tempest—in which a banished duke with magical servants seeks to reclaim his throne—was deemed inappropriate for schools, as the law prohibited courses that “promote the overthrow of the United States government, promote resentment toward a race or class of people, are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group or advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.”

A Light in the Attic, Shel Silverstein

A Light in the Attic, Shel Silverstein

Known for his whimsical illustrations and verses about mischievous children, transformed adults, and strange monsters and beasts, Shel Silverstein published his second poetry collection, A Light in the Attic, in 1981. The book spent 182 weeks on The New York Times general nonfiction bestseller list and spent fourteen weeks in the number one spot.

However, Silverstein’s books were accused of being not for children, encouraging bad behavior, and addressing topics some people deemed inappropriate for kids. Challengers at two elementary schools in Wisconsin said one poem “encourages children to break dishes so they won’t have to dry them,” and that other poems “glorified Satan, suicide, and cannibalism, and also encouraged children to be disobedient.”

The book was so contested that it became number fifty-one on the list of 100 most frequently challenged books in the 1990s.

The Greek poet Sappho lived on the island of Lesbos and is famously known for her poems of romantic longing and her affairs with other women. Though Plato referred to her as the “tenth muse,” her sexuality occasionally overshadowed her work, which was frequently viewed as obscene and objectionable. In 180 AD, the Assyrian ascetic Tatian decried Sappho as a “whorish woman, love-crazy, who sang about her own licentiousness.”

Before it was destroyed, the library of Alexandria housed nine collections of Sappho’s poems. But in 380 AD, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, the bishop of Constantinople, ordered her work burned. Later, in 1073, Pope Gregory VII also ordered that her work be publicly burned. Most of her work was destroyed; only one complete poem survived—until the discovery of some more of her poem fragments by scholars in 1898.

Dlatego żyjemy (That’s What We Live For), Wislawa Szymborska

Dlatego żyjemy (That’s What We Live For), Wislawa Szymborska

Wislawa Szymborksa is considered one of the major modern Polish poets; she published several poetry collections and was awarded a Nobel Prize in literature in 1996. Szymborska spent much of her life in a Stalinist Poland, in which socialism was enforced upon Polish artists.

In 1949 her first book, Dlatego żyjemy, was set for publication but was banned for being too preoccupied with the war and not loyal enough to the socialist regime. The book would not be published until 1952. By 1957, however, Szymborska had renounced Communism and her early poetry, which she viewed as no longer representative of her as a writer.

Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

Seminal to the history of American verse, Leaves of Grass, a frank and sensual celebration of America and the human body, would later be considered a classic that established Whitman as one of the originators of a uniquely American poetic voice.

Fellow writer and critic Ralph Waldo Emerson attempted to persuade Whitman to drop some controversial, sexualized passages, but Whitman refused. However, when it was first published in 1855, Emerson wrote a letter to Whitman praising the collection: “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.”

Many critics did not give such a warm welcome to the book, which they denounced as crude and offensive. The Watch and Ward Society in Boston and the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice pressured booksellers to suppress the sale of the book, and the Society of Suppression of Vice then sought to obtain a legal ban of a new edition of the book in Boston, which caused it to be famously “banned in Boston” in 1882.

Howl,

Howl, D. H. Lawrence

D. H. Lawrence