In this document from the archive, Denise Levertov edits her statement for Donald Allen’s anthology, the seminal work The New American Poetry: 1945–1960, widely known as one of the first collections of counter-cultural, avant-garde American poetry.

Allen’s anthology brought to mainstream attention the works of many poets who are now known as part of the canon of American poetry: John Ashbery, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Frank O’Hara, Gary Snyder, and, of course, Levertov, among others. The New American Poetry categorized the experimental poets by the schools and movements many still associate them with today: the Black Mountain School, the San Francisco Renaissance, the Beat Movement, and the New York School.

Levertov was included in Allen’s list of Black Mountain poets, alongside Paul Blackburn, Paul Carroll, Creeley, Edward Dorn, Duncan, Larry Eigner, Charles Olson, and Joel Oppenheimer.

Levertov, whose first book brought her recognition as one of a group of British poets dubbed the “New Romantics,” later became associated with the Black Mountain poets through her husband’s friendship with Creeley and her own friendship with Duncan, with whom she exchanged over 500 letters. Her work, too, became associated with the movement after some of her poems were published in the Black Mountain Review, edited by Creeley, in the 1950s.

Though Levertov herself disclaimed membership in any poetic school, her inclusion in the groundbreaking anthology positively impacted her career. The first book she published in America, Here and Now (City Lights, 1956), won the praise of Creeley, Duncan, Kenneth Rexroth, and William Carlos Williams, and her next book, With Eyes at the Back of our Heads (New Directions, 1959), established her as one of the great American poets of the time, but it was her inclusion in The New American Poetry that further cemented her place of importance in modern American poetry.

Fifteen of the forty-four contributors to the anthology submitted statements on poetics, including Creeley, Duncan, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones, O’Hara, Olson, Gary Snyder, and Jack Spicer. Levertov, who was one of only four women poets included in the anthology, was the only woman with a statement.

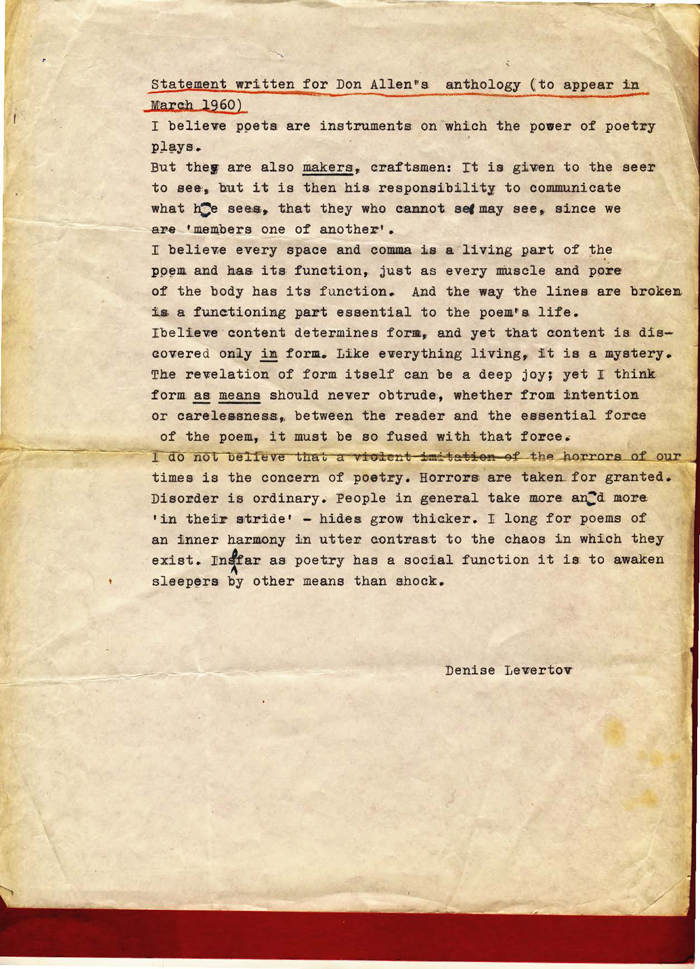

Levertov’s confident, energized statement begins with a general declaration about the duty of the poet:

“I believe poets are instruments on which the power of poetry

plays. But they are also makers, craftsmen: It is given to the

seer to see, but it is then his responsibility to communicate

what he sees, that they who cannot see may see, since we

are ‘members one of another.’”

She then goes into a more specific discussion of craft: “I believe every space and comma is a living part of the poem and has its function.”

The surprising part of Levertov’s statement is the final paragraph, in which she discusses the relationship between the poem and the “horrors of our time”: “I do not believe that a violent imitation of the horrors of our times is the concern of poetry. … I long for poems of an inner harmony in utter contrast to the chaos in which they exist.”

Despite Levertov’s firm stance on poetics here, her own poetry soon became charged with activist and feminist themes during the 1960s. In Denise Levertov: A Poet’s Life, author Dana Greene writes:

“Levertov’s poetry in the subsequent 1960s and early 1970s

seemed to many to be in direct contradiction to this

statement in which she clearly separates contemporary

events and the concerns of poetry. As the ‘horrors’ of the

Vietnam War increased and the ‘disorder’ in her personal

life augmented, Levertov did not take these events ‘in

stride.’ … While she might ‘long for poems of an inner

harmony,’ few would be forthcoming. Her poems

shocked, and she meant them to do so.”

One of Levertov’s most memorable, emotionally charged collections, The Sorrow Dance, was a result of this change; the collection, published in 1967, encompassed her reactions toward the Vietnam War and the death of her sister. However, her later work would ultimately reach back toward this sense of “inner harmony,” with poems more spiritual in nature, juxtaposing humanity with the natural and the divine.

For the next few decades, Levertov would continue to publish more than twenty volumes of poetry, including The Freeing of the Dust (New Directions, 1975), winner of the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize.