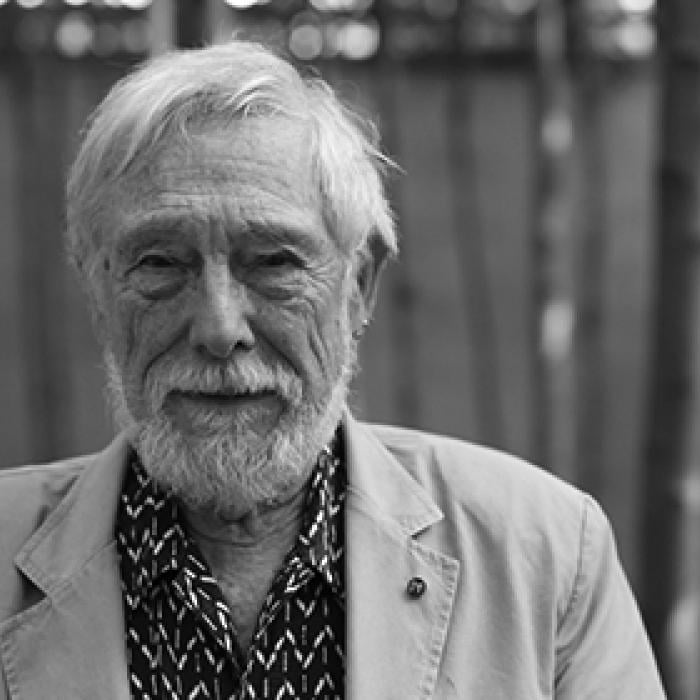

Jack Spicer

Jack Spicer was born John Lester Spicer on January 30, 1925, in Los Angeles. He was the elder of two sons. His parents, Dorothy Clause and John Lovely Spicer, were Midwesterners who met and married in Hollywood and ran a small hotel business. They followed the era’s conventional beliefs about child development and sent Spicer to Minnesota when he was three to live with his grandmother during his mother's pregnancy. This sudden rift left Spicer with a lasting resentment toward his brother and a sense of alienation from his family. Years later, when Spicer left his family in Los Angeles to attend the University of California at Berkeley, he refused to talk about his past and became so secretive that many believed him to be an orphan.

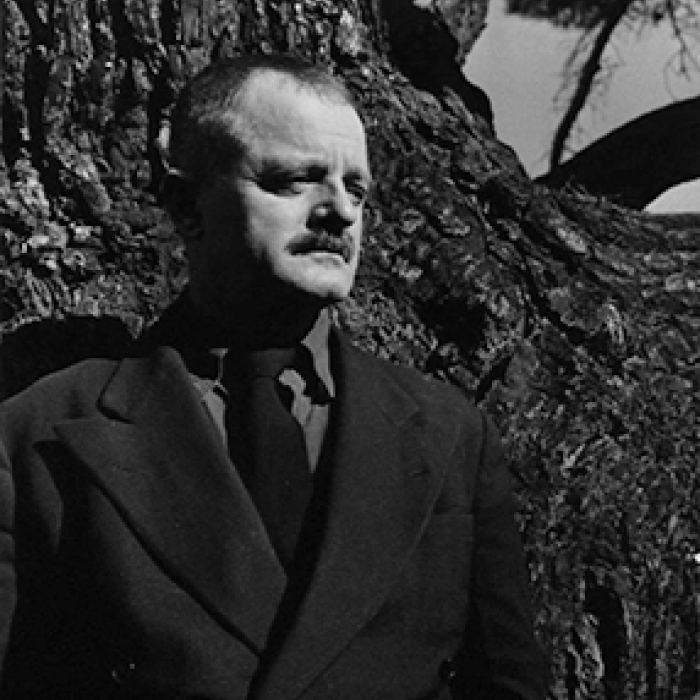

While in Berkeley, Spicer became involved in liberal politics and the local literary scene, particularly the group centered around Kenneth Rexroth. He quickly met other poets, including Robin Blaser and Robert Duncan, with whom he became close. Duncan, seven years his senior, had lived what seemed to Spicer the fantasy life of a poet: he had graduated from Berkeley, hitchhiked across the country, spent time with famous writers, and worked as an editor on the East Coast.

Duncan, who according to the poet Leonard Wolf was the “most ‘out’ man that ever lived,” inspired the more timid Spicer to embrace his sexuality. The two poets, along with Blaser, were inventors of their own myth, humorously naming their culture and poetics the “Berkeley Renaissance.” Later in life, Spicer would refer to the year he made these new friends, 1946, as the year of his birth.

Spicer left Berkeley after losing his teaching assistantship in the linguistics department for his refusal to sign a “Loyalty Oath,” a provision of the Sloan-Levering Act that required all California state employees in 1950 to swear their loyalty to the United States. He briefly moved to Minnesota where a sympathetic professor helped him get a job in linguistics.

He soon returned to Berkeley in 1952, though Duncan had already moved across the Bay to San Francisco, a departure that Spicer considered a betrayal to their Berkeley Renaissance ethos. He resumed his academic work and completed all but his thesis for a PhD in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse.

In 1953, Spicer was hired as the head of the new humanities department at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), a job that eventually brought him to San Francisco. His role at CSFA connected him with a burgeoning arts community, and on Halloween in 1954, Spicer and five painter friends opened the “6” Gallery. Spicer soon left this position and moved east. In his absence, the “6” Gallery became the scene of the famous reading in October 1955 that featured the first public performance by Allen Ginsberg of “Howl” and helped launch the Beat movement.

During this same time, Spicer developed his practice of “poetry as dictation” and began to transcribe the poems that would become his first collection, After Lorca, which was published in 1957. He defined the poet as a “radio” able to collect transmission from the “invisible world,” as opposed to believing that poetry was driven by a poet’s voice and will.

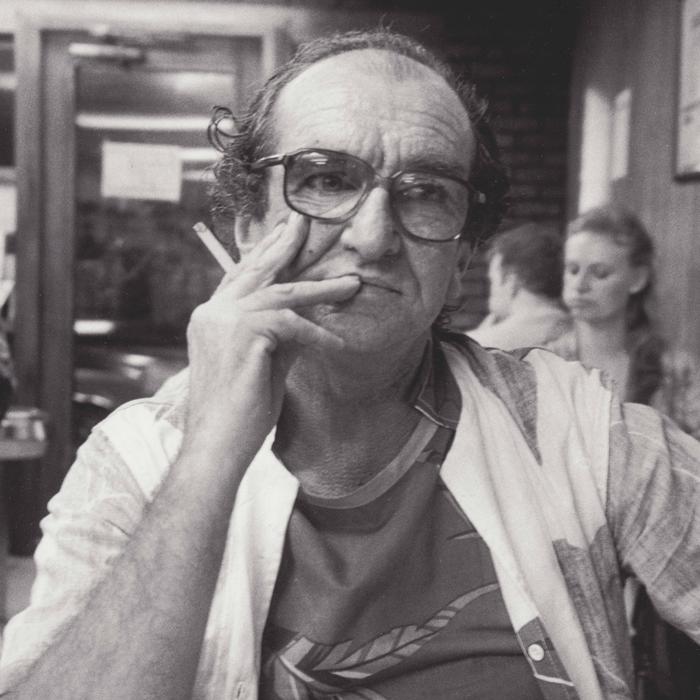

Spicer despised New York City and relocated to Boston where he briefly worked in the rare books room at Boston Public Library. Blaser was also in Boston at this time, and the pair made contact with a number of local poets, including John Wieners. However, Spicer continued to suffer from alcoholism and depression, and once again lost his job. He then returned to San Francisco where Duncan was able to use his position at the Poetry Center at San Francisco State College to offer Spicer the opportunity to teach his own workshop. Titled “Poetry and Magic,” the workshop had a notable influence on several enrolled poets, including Jack Gilbert, James Broughton, and Duncan himself.

Over the next few years, many followers were attracted to Spicer and the lyric beauty and formal invention of his work. This group, which became known as the “Spicer Circle,” met in North Beach bars and San Francisco parks to discuss poetry and life. In 1960, much of his group left North Beach to pursue disparate interests and Spicer responded to the loss by drinking even more heavily. His increasing depression and alcoholism began to destroy even his closest friendships. He was cruel to Duncan, criticizing his desire for recognition, and their friendship rapidly dissolved. When he was once again fired in March of 1964, this time from a job at University of California in Berkeley, Spicer had nowhere to turn and few true friends to fall back on. The only job he could find was as a research assistant at Stanford, which proved unsatisfying.

In February of 1965, Spicer was invited to give a reading at the University of British Columbia. He returned that summer to give a number of talks now known as Spicer’s “Vancouver Lectures.” The success of these events gave Spicer a renewed sense of accomplishment: he made new contacts with poets; he was invited to return to Vancouver and was even offered a teaching job; and his alcoholism seemed to be waning. But, before he could emigrate, Spicer collapsed into a coma in his building elevator on the last day of July 1965. He died on August 17 in the poverty ward of San Francisco General Hospital.