Ink runs from the corners of my mouth.

There is no happiness like mine.

I have been eating poetry.

The librarian does not believe what she sees.

Her eyes are sad

and she walks with her hands in her dress.

The poems are gone.

The light is dim.

The dogs are on the basement stairs and coming up.

Their eyeballs roll,

their blond legs burn like brush.

The poor librarian begins to stamp her feet and weep.

She does not understand.

When I get on my knees and lick her hand,

she screams.

I am a new man.

I snarl at her and bark.

I romp with joy in the bookish dark.

From Collected Poems by Mark Strand. Copyright © 2014 by Mark Strand. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

You should lie down now and remember the forest, for it is disappearing-- no, the truth is it is gone now and so what details you can bring back might have a kind of life. Not the one you had hoped for, but a life --you should lie down now and remember the forest-- nonetheless, you might call it "in the forest," no the truth is, it is gone now, starting somewhere near the beginning, that edge, Or instead the first layer, the place you remember (not the one you had hoped for, but a life) as if it were firm, underfoot, for that place is a sea, nonetheless, you might call it "in the forest," which we can never drift above, we were there or we were not, No surface, skimming. And blank in life, too, or instead the first layer, the place you remember, as layers fold in time, black humus there, as if it were firm, underfoot, for that place is a sea, like a light left hand descending, always on the same keys. The flecked birds of the forest sing behind and before no surface, skimming. And blank in life, too, sing without a music where there cannot be an order, as layers fold in time, black humus there, where wide swatches of light slice between gray trunks, Where the air has a texture of drying moss, the flecked birds of the forest sing behind and before: a musk from the mushrooms and scalloped molds. They sing without a music where there cannot be an order, though high in the dry leaves something does fall, Nothing comes down to us here. Where the air has a texture of drying moss, (in that place where I was raised) the forest was tangled, a musk from the mushrooms and scalloped molds, tangled with brambles, soft-starred and moving, ferns And the marred twines of cinquefoil, false strawberry, sumac-- nothing comes down to us here, stained. A low branch swinging above a brook in that place where I was raised, the forest was tangled, and a cave just the width of shoulder blades. You can understand what I am doing when I think of the entry-- and the marred twines of cinquefoil, false strawberry, sumac-- as a kind of limit. Sometimes I imagine us walking there (. . .pokeberry, stained. A low branch swinging above a brook) in a place that is something like a forest. But perhaps the other kind, where the ground is covered (you can understand what I am doing when I think of the entry) by pliant green needles, there below the piney fronds, a kind of limit. Sometimes I imagine us walking there. And quickening below lie the sharp brown blades, The disfiguring blackness, then the bulbed phosphorescence of the roots. But perhaps the other kind, where the ground is covered, so strangely alike and yet singular, too, below the pliant green needles, the piney fronds. Once we were lost in the forest, so strangely alike and yet singular, too, but the truth is, it is, lost to us now.

From The Forest by Susan Stewart, published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 1995 by Susan Stewart. Reprinted by permission of the author. All rights reserved.

noctes illustratas

(the night has houses)

and the shadow of the fabulous

broken into handfuls--these

can be placed at regular intervals,

candles

walking down streets at times eclipsed by trees.

Certain cells, it's said, can generate light on their own.

There are organisms that could fit on the head of a pin

and light entire rooms.

Throughout the Middle Ages, you could hire a man

on any corner with a torch to light you home

were lamps made of horn

and from above a loom of moving flares, we watched

Notre Dame seem small.

Now the streets stand still.

By 1890, it took a pound of powdered magnesium

to photograph a midnight ball.

While as early as 50 BCE, riotous soldiers leaving a Roman bath

sliced through the ropes that hung the lamps from tree to tree

and aloft us this

new and larger room

Flambeaux the arboreal

was the life of Julius Caesar

in whose streets

in which a single step could rd.

We opened all our windows

and looked out on a listening world laced here and there with points of light,

Notre Dame of the Unfinished Sky,

oil slicks burning on the river; someone down on the corner

striking a match to read by.

Some claim Paris was the first modern city to light its streets.

The inhabitants were ordered

in 1524 to place a taper in every window in the dark there were 912 streets

walked into this arc until by stars

makes steps sharp, you are

and are not alone

by public decree

October 1558: the lanterns were similar to those used in mines:

"Once

we were kings"

and down into the spiral of our riches

still reign: falots or great vases of pitch lit

at the crossroads

--and thus were we followed

through a city of thieves--which,

but a few weeks later, were replaced by chandeliers.

While others claim all London was alight by 1414.

There it was worded:

Out of every window, come a wrist with a lanthorn

and were told

hold it there

and be on time

and not before

and watched below

the faces lit, and watched the faces pass. And turned back in

(the face goes on) and watched the lights go out.

Here the numbers are instructive:

In the early 18th century, London hung some 15,000 lamps.

And now we find (1786) they've turned to crystal, placed precisely

each its own distance, small in islands, large in the time it would take to run.

And Venice started in 1687 with a bell

upon the hearing of which, we all in unison

exit,

match in hand, and together strike them against an upper tooth and touch

the tiny flame to anything, and when times get rough (crime up, etc.) all we

have to do is throw oil out upon the canals to make the lighting uncommonly

extensive. Sometimes we do it just to shock the rest of Europe, and at other

times because we find it beautiful.

Says Libanius

Night differs us

Without us

noctes illustratas

Though in times of public grief

when the streets were left unlit, on we went, just

dark marks in the markets and voices in the cafes, in the crowded squares,

a single touch, the living, a lantern

swinging above the door any time a child is born, be it

Antioch, Syria, or Edessa--

and then there were the festivals,

the festum encaeniorum, and others in which

they call idolatrous, these torches

half a city wide

be your houses.

From Goest by Cole Swensen. Copyright © 2004 by Cole Swensen. Reprinted by permission of Alice James Books. All rights reserved.

(at St. Mary’s)

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

From Quilting: Poems 1987–1990 by Lucille Clifton. Copyright © 2001 by Lucille Clifton. Reprinted with permission of BOA Editions Ltd. All rights reserved.

Then the pulse. Then a pause. Then twilight in a box. Dusk underfoot. Then generations. * Then the same war by a different name. Wine splashing in a bucket. The erection, the era. Then exit Reason. Then sadness without reason. Then the removal of the ceiling by hand. * Then pages & pages of numbers. Then the page with the faint green stain. Then the page on which Prince Theodore, gravely wounded, is thrown onto a wagon. Then the page on which Masha weds somebody else. Then the page that turns to the story of somebody else. Then the page scribbled in dactyls. Then the page which begins Exit Angel. Then the page wrapped around a dead fish. Then the page where the serfs reach the ocean. Then a nap. Then the peg. Then the page with the curious helmet. Then the page on which millet is ground. Then the death of Ursula. Then the stone page they raised over her head. Then the page made of grass which goes on. * Exit Beauty. * Then the page someone folded to mark her place. Then the page on which nothing happens. The page after this page. Then the transcript. Knocking within. Interpretation, then harvest. * Exit Want. Then a love story. Then a trip to the ruins. Then & only then the violet agenda. Then hope without reason. Then the construction of an underground passage between us.

From Facts for Visitors by Srikanth Reddy. Copyright © 2004 by the Regents of the University of California. Reprinted by permission of the University of California Press. All rights reserved.

I was outside St. Cecelia's Rectory

smoking a cigarette when a goat appeared beside me.

It was mostly black and white, with a little reddish

brown here and there. When I started to walk away,

it followed. I was amused and delighted, but wondered

what the laws were on this kind of thing. There's

a leash law for dogs, but what about goats? People

smiled at me and admired the goat. "It's not my goat,"

I explained. "It's the town's goat. I'm just taking

my turn caring for it." "I didn't know we had a goat,"

one of them said. "I wonder when my turn is." "Soon,"

I said. "Be patient. Your time is coming." The goat

stayed by my side. It stopped when I stopped. It looked

up at me and I stared into its eyes. I felt he knew

everything essential about me. We walked on. A police-

man on his beat looked us over. "That's a mighty

fine goat you got there," he said, stopping to admire.

"It's the town's goat," I said. "His family goes back

three-hundred years with us," I said, "from the beginning."

The officer leaned forward to touch him, then stopped

and looked up at me. "Mind if I pat him?" he asked.

"Touching this goat will change your life," I said.

"It's your decision." He thought real hard for a minute,

and then stood up and said, "What's his name?" "He's

called the Prince of Peace," I said. "God! This town

is like a fairy tale. Everywhere you turn there's mystery

and wonder. And I'm just a child playing cops and robbers

forever. Please forgive me if I cry." "We forgive you,

Officer," I said. "And we understand why you, more than

anybody, should never touch the Prince." The goat and

I walked on. It was getting dark and we were beginning

to wonder where we would spend the night.

From Lost River by James Tate, published by Sarabande Books, Inc. Copyright © 2003 by James Tate. Reprinted by permission of Sarabande Books and the author. All rights reserved.

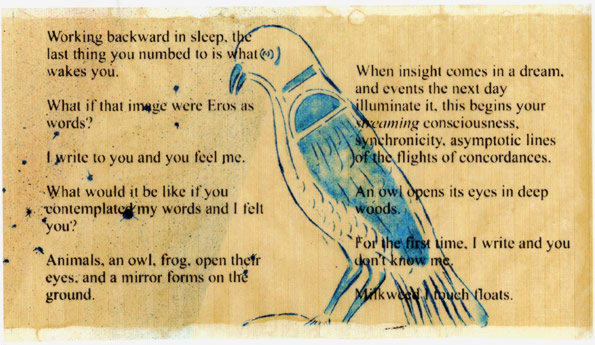

Poem by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

Illustration by Kiki Smith

Working backward in sleep, the

last thing you numbed to is what

wakes you.

What if that image were Eros as

words?

What would it be like if you

contemplated my words and I felt

you?

Animals, an owl, frog, open their

eyes, and a mirror forms on the

ground.

When insight comes in a dream,

and events the next day

illuminate it, this begins your

streaming consciousness,

synchronicity, asymptotic lines

of the flights of concordances.

An owl opens its eyes in deep

woods.

For the first time, I write and you

don't know me.

Milkweed I touch floats.

From Concordance by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Kiki Smith. Published by the Rutgers Center for Innovative Print and Paper.

The radio animals travel in lavender clouds. They are always chattering, they are always cold. Look directly at the buzzing blur and you'll see twitter, hear flicker—that's how much they ignore the roadblocks. They're rabid with doubt. When a strong sunbeam hits the cloud, the heat in their bones lends them a temporary gravity and they sink to the ground. Their little thudding footsteps sound like "Testing, testing, 1 2 3" from a far-away galaxy. Like pitter and its petite echo, patter. On land, they scatter into gutters and alleyways, pressing their noses into open Coke cans, transmitting their secrets to the silver circle at the bottom of the can. Of course we've wired their confessionals and hired a translator. We know that when they call us Walkie Talkies they mean it scornfully, that they disdain our in and outboxes, our tests of true or false. |

Copyright © 2010 by Matthea Harvey. Used with permission of the author.

One narcissus among the ordinary beautiful flowers, one unlike all the others! She pulled, stooped to pull harder— when, sprung out of the earth on his glittering terrible carriage, he claimed his due. It is finished. No one heard her. No one! She had strayed from the herd. (Remember: go straight to school. This is important, stop fooling around! Don't answer to strangers. Stick with your playmates. Keep your eyes down.) This is how easily the pit opens. This is how one foot sinks into the ground.

“Persephone, Falling,” from Mother Love by Rita Dove. Copyright © 1995 by Rita Dove. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

When Hades decided he loved this girl

he built for her a duplicate of earth,

everything the same, down to the meadow,

but with a bed added.

Everything the same, including sunlight,

because it would be hard on a young girl

to go so quickly from bright light to utter darkness

Gradually, he thought, he'd introduce the night,

first as the shadows of fluttering leaves.

Then moon, then stars. Then no moon, no stars.

Let Persephone get used to it slowly.

In the end, he thought, she'd find it comforting.

A replica of earth

except there was love here.

Doesn't everyone want love?

He waited many years,

building a world, watching

Persephone in the meadow.

Persephone, a smeller, a taster.

If you have one appetite, he thought,

you have them all.

Doesn't everyone want to feel in the night

the beloved body, compass, polestar,

to hear the quiet breathing that says

I am alive, that means also

you are alive, because you hear me,

you are here with me. And when one turns,

the other turns—

That's what he felt, the lord of darkness,

looking at the world he had

constructed for Persephone. It never crossed his mind

that there'd be no more smelling here,

certainly no more eating.

Guilt? Terror? The fear of love?

These things he couldn't imagine;

no lover ever imagines them.

He dreams, he wonders what to call this place.

First he thinks: The New Hell. Then: The Garden.

In the end, he decides to name it

Persephone's Girlhood.

A soft light rising above the level meadow,

behind the bed. He takes her in his arms.

He wants to say I love you, nothing can hurt you

but he thinks

this is a lie, so he says in the end

you're dead, nothing can hurt you

which seems to him

a more promising beginning, more true.

"A Myth of Devotion" from Averno by Louise Glück. Copyright © 2006 by Louise Glück. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

for Octavio There's a book called "A Dictionary of Angels." No one has opened it in fifty years, I know, because when I did, The covers creaked, the pages Crumbled. There I discovered The angels were once as plentiful As species of flies. The sky at dusk Used to be thick with them. You had to wave both arms Just to keep them away. Now the sun is shining Through the tall windows. The library is a quiet place. Angels and gods huddled In dark unopened books. The great secret lies On some shelf Miss Jones Passes every day on her rounds. She's very tall, so she keeps Her head tipped as if listening. The books are whispering. I hear nothing, but she does.

From Sixty Poem by Charles Simic. Copyright © 2008 by Charles Simic. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Trade Publishers. All rights reserved.

despite books kindled in electronic flames. The locket of bookish love still opens and shuts. But its words have migrated to a luminous elsewhere. Neither completely oral nor written — a somewhere in between. Then will oak, willow, birch, and olive poets return to their digital tribes — trees wander back to the forest?

Copyright © 2011 by Elaine Equi. Reprinted from Click and Clone with the permission of Coffee House Press.