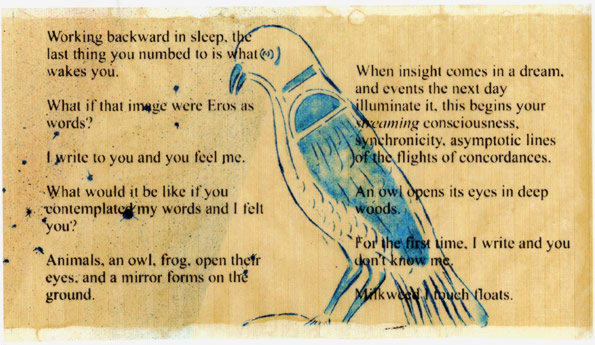

Poem by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

Illustration by Kiki Smith

Working backward in sleep, the

last thing you numbed to is what

wakes you.

What if that image were Eros as

words?

What would it be like if you

contemplated my words and I felt

you?

Animals, an owl, frog, open their

eyes, and a mirror forms on the

ground.

When insight comes in a dream,

and events the next day

illuminate it, this begins your

streaming consciousness,

synchronicity, asymptotic lines

of the flights of concordances.

An owl opens its eyes in deep

woods.

For the first time, I write and you

don't know me.

Milkweed I touch floats.

From Concordance by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Kiki Smith. Published by the Rutgers Center for Innovative Print and Paper.

RAGE:

Sing, Goddess, Achilles' rage,

Black and murderous, that cost the Greeks

Incalculable pain, pitched countless souls

Of heroes into Hades' dark,

And left their bodies to rot as feasts

For dogs and birds, as Zeus' will was done.

Begin with the clash between Agamemnon--

The Greek warlord--and godlike Achilles.

Which of the immortals set these two

At each other's throats?

Apollo

Zeus' son and Leto's, offended

By the warlord. Agamemnon had dishonored

Chryses, Apollo's priest, so the god

Struck the Greek camp with plague,

And the soldiers were dying of it.

From The Iliad, lines 1-17, by Homer, translated by Stanley Lombardo and published by Hackett Publishing. © 1997 by Stanley Lombardo. Used with permission of Hackett Publishing Co., Inc., Indianapolis, IN and Cambridge, MA. All rights reserved.

Anger be now your song, immortal one, Akhilleus' anger, doomed and ruinous, that caused the Akhaians loss on bitter loss and crowded brave souls into the undergloom, leaving so many dead men--carrion for dogs and birds; and the will of Zeus was done. Begin it when the two men first contending broke with one another-- the Lord Marshal Agamémnon, Atreus' son, and Prince Akhilleus. Among the gods, who brought this quarrel on? The son of Zeus by Lêto. Agamémnon angered him, so he made a burning wind of plague rise in the army: rank and file sickened and died for the ill their chief had done in despising a man of prayer.

From Iliad, by Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald and published by Anchor Books © 1975. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

"Sleeping so? Thou hast forgotten me, Akhilleus. Never was I uncared for in life but am in death. Accord me burial in all haste: let me pass the gates of Death. Shades that are images of used-up men motion me away, will not receive me among their hosts beyond the river. I wander about the wide gates and the hall of Death. Give me your hand. I sorrow. When thou shalt have allotted me my fire I will not fare here from the dark again. As living men we'll no more sit apart from our companions, making plans. The day of wrath appointed for me at my birth engulfed and took me down. Thou too, Akhilleus, face iron destiny, godlike as thou art, to die under the wall of highborn Trojans. One more message, one behest, I leave thee: not to inter my bones apart from thine but close together, as we grew together, in thy family's hall. Menoitios from Opoeis had brought me, under a cloud, a boy still, on the day I killed the son of Lord Amphídamas--though I wished it not-- in childish anger over a game of dice. Pêleus, master of horse, adopted me and reared me kindly, naming me your squire. So may the same urn hide our bones, the one of gold your gracious mother gave."

Lines 80-106 from "A Friend Consigned to Death" in The Iliad by Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald. Translation copyright © 1974 by Robert Fitzgerald. Copyright © 2004 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved.

Man looking into the sea, taking the view from those who have as much right to it as you have to yourself, it is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing, but you cannot stand in the middle of this; the sea has nothing to give but a well excavated grave. The firs stand in a procession, each with an emerald turkey-foot at the top, reserved as their contours, saying nothing; repression, however, is not the most obvious characteristic of the sea; the sea is a collector, quick to return a rapacious look. There are others besides you who have worn that look— whose expression is no longer a protest; the fish no longer investigate them for their bones have not lasted: men lower nets, unconscious of the fact that they are desecrating a grave, and row quickly away—the blades of the oars moving together like the feet of water-spiders as if there were no such thing as death. The wrinkles progress among themselves in a phalanx—beautiful under networks of foam, and fade breathlessly while the sea rustles in and out of the seaweed; the birds swim through the air at top speed, emitting cat-calls as heretofore— the tortoise-shell scourges about the feet of the cliffs, in motion beneath them; and the ocean, under the pulsation of lighthouses and noise of bellbuoys, advances as usual, looking as if it were not that ocean in which dropped things are bound to sink— in which if they turn and twist, it is neither with volition nor consciousness.

From The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore. Copyright © 1981 by Marianne Craig Moore. Reprinted with permission of Marianne Craig Moore. All rights reserved.

They have watered the street,

It shines in the glare of lamps,

Cold, white lamps,

And lies

Like a slow-moving river,

Barred with silver and black.

Cabs go down it,

One,

And then another,

Between them I hear the shuffling of feet.

Tramps doze on the window-ledges,

Night-walkers pass along the sidewalks.

The city is squalid and sinister,

With the silver-barred street in the midst,

Slow-moving,

A river leading nowhere.

Opposite my window,

The moon cuts,

Clear and round,

Through the plum-coloured night.

She cannot light the city:

It is too bright.

It has white lamps,

And glitters coldly.

I stand in the window and watch the

moon.

She is thin and lustreless,

But I love her.

I know the moon,

And this is an alien city.

This poem is in the public domain.

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

From Ahead of All Parting: Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell and published by Modern Library. © 1995 by Stephen Mitchell. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

I too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond all this fiddle.

Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers that there is in

it after all, a place for the genuine.

Hands that can grasp, eyes

that can dilate, hair that can rise

if it must, these things are important not because a

high-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because they are

useful; when they become so derivative as to become unintelligible, the

same thing may be said for all of us—that we

do not admire what

we cannot understand. The bat,

holding on upside down or in quest of something to

eat, elephants pushing, a wild horse taking a roll, a tireless wolf under

a tree, the immovable critic twinkling his skin like a horse that feels a flea, the base—

ball fan, the statistician—case after case

could be cited did

one wish it; nor is it valid

to discriminate against “business documents and

school-books”; all these phenomena are important. One must make a distinction

however: when dragged into prominence by half poets, the result is not poetry,

nor till the autocrats among us can be

“literalists of

the imagination”—above

insolence and triviality and can present

for inspection, imaginary gardens with real toads in them, shall we have

it. In the meantime, if you demand on the one hand, in defiance of their opinion—

the raw material of poetry in

all its rawness, and

that which is on the other hand,

genuine, then you are interested in poetry.

From Others for 1919: An Anthology of the New Verse (Nicholas L. Brown, 1920), edited by Alfred Kreymborg. This poem is in the public domain.

She looked over his shoulder

For vines and olive trees,

Marble well-governed cities

And ships upon untamed seas,

But there on the shining metal

His hands had put instead

An artificial wilderness

And a sky like lead.

A plain without a feature, bare and brown,

No blade of grass, no sign of neighborhood,

Nothing to eat and nowhere to sit down,

Yet, congregated on its blankness, stood

An unintelligible multitude,

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign.

Out of the air a voice without a face

Proved by statistics that some cause was just

In tones as dry and level as the place:

No one was cheered and nothing was discussed;

Column by column in a cloud of dust

They marched away enduring a belief

Whose logic brought them, somewhere else, to grief.

She looked over his shoulder

For ritual pieties,

White flower-garlanded heifers,

Libation and sacrifice,

But there on the shining metal

Where the altar should have been,

She saw by his flickering forge-light

Quite another scene.

Barbed wire enclosed an arbitrary spot

Where bored officials lounged (one cracked a joke)

And sentries sweated for the day was hot:

A crowd of ordinary decent folk

Watched from without and neither moved nor spoke

As three pale figures were led forth and bound

To three posts driven upright in the ground.

The mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes liked to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

She looked over his shoulder

For athletes at their games,

Men and women in a dance

Moving their sweet limbs

Quick, quick, to music,

But there on the shining shield

His hands had set no dancing-floor

But a weed-choked field.

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy; a bird

Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third,

Were axioms to him, who'd never heard

Of any world where promises were kept,

Or one could weep because another wept.

The thin-lipped armorer,

Hephaestos, hobbled away,

Thetis of the shining breasts

Cried out in dismay

At what the god had wrought

To please her son, the strong

Iron-hearted man-slaying Achilles

Who would not live long.

From The Shield of Achilles by W. H. Auden, published by Random House. Copyright © 1955 W. H. Auden, renewed by The Estate of W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.