In the Fall-Winter 2018 issue of American Poets, Maya Phillips reviews twelve of the year’s most anticipated poetry collections.

mobileMenu

- Poems

- Poets

- Poem-a-Day

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

User account menu

Books Noted, Fall-Winter 2018

Page submenu block

Graywolf Press, September 2018

As its title implies, Human Hours, Catherine Barnett’s follow-up to her James Laughlin Award–winning collection, The Game of Boxes (Graywolf Press, 2012), is a book-long meditation on time marked by vigorous inquiry. As she writes in “Accursed Questions, i,” “So much depends upon the kindness of questions. And the questions we cannot not speak of.” Barnett’s interrogations are unrelenting, occasionally riddles, like koans, posed in response to life’s challenges....

Copper Canyon Press, October 2018

Dissolve, Sherwin Bitsui’s third poetry collection, is divided into two sections, the first: a two-page poem called “The Caravan,” in which the speaker encounters a young man beaten down and broken against the backdrop of the city, where “neon embers / stripe the asphalt’s blank page / where this story pens itself nightly.” But we don’t remain in the city for long; “The Caravan” serves as a prelude to the main section of the book, the extended lyrical poem “Dissolve”....

Duke University Press, September 2018

In Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016, physician-cum-poet Rafael Campo presents a career in medicine through poems that recount nights spent in the hospital (“A quiet hospital is infinite, / The polished, ice-white floors, the darkened halls / That lead to almost anywhere, to death / Or ghostly, lighted Coke machines”) and the patients he has seen. In poems such as “Tuesday Morning,” Campo reflects on the limits of medicine and the doctor’s role as healer....

W. W. Norton, October 2018

A Portrait of the Self as Nation: New and Selected Poems reflects a literary career—and collection—of fiercely anti-colonialist, anti-xenophobic, feminist poems, from 1987’s Dwarf Bamboo through 2009’s Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen and new poems. The selected poems show a consistent focus across Marilyn Chin’s books—each pairing the political and cultural histories of China alongside fixtures of American identity, accounting instances of othering, orientalism, and violent culture clashes....

Beacon Press, October 2018

In the nineteenth century, physician J. Marion Sims, known as the “the father of modern gynecology,” pioneered new surgical tools and techniques in the field by experimenting on enslaved women, usually without anesthesia. In Anarcha Speaks: A History in Poems, selected by Tyehimba Jess as a winner of the National Poetry Series, Dominique Christina tells the story of Anarcha, one of Sims’s most frequent test subjects, in a series of narrative poems written almost entirely in her voice.

Omnidawn Publishing, October 2018

In Norma Cole’s Fate News, a book whose title turns on its head the derisive “fake news,” she offers an array of experimental musings on time and art in four sections. In the opening poem she begins in space, with creation and destruction as her focus, and she continues through the first section with a series of occasional poems, elegies, and others written in dedication. Cole’s poems simultaneously shrink the substantial in their gaze (“Distant mountain ridgelines / flatten to paper in daylight”) and take in the enormousness of the universe.

Milkweed Editions, August 2018

In her fifth collection, The Carrying, Ada Limón unspools anxieties, fears, and griefs with a tenderness that never fully descends into full-blown despair. Limón is a poet who imbues her work with a bevy of small gratitudes and joys that bolster even the heaviest lines, as in the alternatively somber and jubilant “Dead Stars”: “We’re dead stars too, my mouth is full / of dust and I wish to reclaim the rising.” There are poems of self-interrogation and disturbing discoveries....

Princeton University Press, October 2018

Dora Malech’s third poetry collection, Stet, takes its name from the Latin term, meaning “let it stand,” used by editors to reject a suggested change in a text. It’s a fitting title for this collection, which challenges its own language in a kind of ouroboros of statement and retraction through the use of anagrams, erasure, and Oulipo poetry. “Destroy (de-story). / I to pen: / open it,” Malech declares early on in the book, and she does just that throughout.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 2019

In his follow-up to the award-winning collection In the Language of My Captor (Wesleyan University Press, 2017), Shane McCrae exposes the hypocrisy and irony beneath the American ideal. Most of the book’s poems are direct addresses to the country that question the inequalities among its citizens, as in the devastating “Purchase,” when the speaker asserts: “America I was born incapable / Of owning what I work for.”

Wave Books, September 2018

It is hard not to be charmed by Chelsey Minnis’s dangerously flirtatious Baby, I Don’t Care, which draws from and is inspired by the glamour, absurdity, and dark underpinning of Hollywood’s golden era. Minnis’s speaker is the kind of woman who wears “high heels by the pool” and likes “to eat sweets in bed while wearing feathered dressing gowns.” Using short five-line stanzas with mostly end-stopped lines, Minnis works within the constraints of a form that reads like a collage of lines taken from the lipsticked mouths of 1950s female starlets.

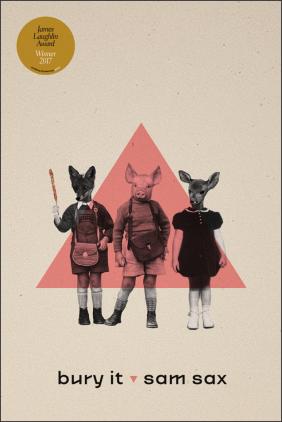

Wesleyan University Press, September 2018

In Sam Sax’s second collection, which won the 2017 James Laughlin Award, queerness meets violence meets devastating grief in poems that mesmerize, especially in their darkest moments. “Bildungsroman,” the second poem in the collection, presents a grotesque origin story, introducing the speaker as something to be feared by his family: “my brother holding me in his hairless arms. says // dad it will be a monster we should bury it.”

Penguin Books, July 2018

Anne Waldman is no novice when it comes to dealing in mythopoetics, and in this new collection she continues some of the work begun in her feminist epic The Iovis Trilogy, once again challenging the patriarchal status quo. Waldman’s characteristic experimental play with form, diction, and syntax is present but under a new guise, that of a trickster speaker whose aural shape-shifting allows for a troubling of the wise-but-conniving female trope in literature and myth.