I know not why, but it is true—it may,

In some way, be because he was a child

Of the fierce sun where I first wept and smiled—

I love the dark-browed Poe. His feverish day

Was spent in dreams inspired, that him beguiled,

When not along his path shone forth one ray

Of light, of hope, to guide him on the way,

That to earth's cares he might be reconciled.

Not one of all Columbia's tuneful choir

Has pitched his notes to such a matchless key

As Poe—the wizard of the Orphic lyre!

Not one has dreamed, has sung, such songs as he,

Who, like an echo came, an echo went,

Singing, back to his mother element.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on April 14, 2019, by the Academy of American Poets.

Take this kiss upon the brow!

And, in parting from you now,

Thus much let me avow:

You are not wrong who deem

That my days have been a dream;

Yet if hope has flown away

In a night, or in a day,

In a vision, or in none,

Is it therefore the less gone?

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

I stand amid the roar

Of a surf-tormented shore,

And I hold within my hand

Grains of the golden sand--

How few! yet how they creep

Through my fingers to the deep,

While I weep--while I weep!

O God! can I not grasp

Them with a tighter clasp?

O God! can I not save

One from the pitiless wave?

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?

This poem is in the public domain.

Smiling dolly with the eyes of blue,

Was it lovely where they fashioned you,

Were there laughing gnomes, and did the breeze

Toss the snow along the Christmas trees?

Tiny hands and chill, and thin rags torn,

Faces drawn with waking night and morn,

Eyes that strained until they could not see,

Little mother, where they fashioned me.

Gold-haired dolly in the silken dress,

Tell me where you found your loveliness,

Were they fairyfolk who clad you so,

Gold wands quivering and wings aglow?

Narrow walls and low, and tumbled bed,

One dim lamp to see to knot the thread,

This was all I saw till dark came down,

Little mother, where they sewed my gown.

Rosy dolly on my Christmas tree,

Tell the lovely things you saw to me,

Were there golden birds and silver dew

In the fairylands they brought you through?

Weary footsteps all and weary faces

Serving crowds within the crowded places,

This was all I saw the Christ-eve through,

Little mother, ere I came to you.

Smiling dolly in the Christmas-green,

What do all these cruel stories mean?

Are there children, then, who cannot say

Thanks to Christ for this his natal day?

Ay, there’s weariness and want and shame,

Pain and evil in the good Lord’s name,

Things the peasant Christ-child could not know

On his quiet birthday long ago!

This poem is in the public domain.

translated from the German by Jessie Lamont

Again the woods are odorous, the lark

Lifts on upsoaring wings the heaven gray

That hung above the tree-tops, veiled and dark,

Where branches bare disclosed the empty day.

After long rainy afternoons an hour

Comes with its shafts of golden light and flings

Them at the windows in a radiant shower,

And rain drops beat the panes like timorous wings.

Then all is still. The stones are crooned to sleep

By the soft sound of rain that slowly dies;

And cradled in the branches, hidden deep

In each bright bud, a slumbering silence lies.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on April 5, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

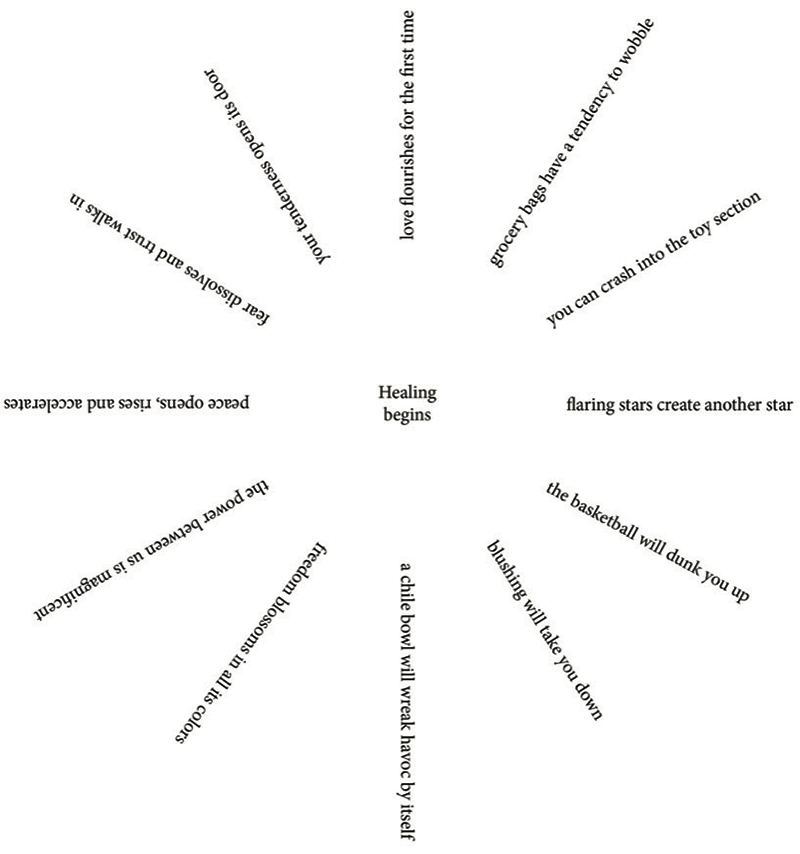

with design by Anthony Cody

Copyright © 2020 by Juan Felipe Herrera. Design by Anthony Cody. Originally published with the Shelter in Poems initiative on poets.org.

Though I was dwelling in a prison house,

My soul was wandering by the carefree stream

Through fields of green with gold eyed daisies strewn,

And daffodils and sunflower cavaliers.

And near me played a little browneyed child,

A winsome creature God alone conceived,

“Oh, little friend,” I begged. “Give me a flower

That I might bear it to my lonely cell.”

He plucked a dandelion, an ugly bloom,

But tenderly he placed it in my hand,

And in his eyes I saw the sign of love.

‘Twas then the dandelion became a rose.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on April 4, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

That in 1869 Miss Jex-Blake and four other women entered for a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh?

That the president of the College of Physicians refused to give the women the prizes they had won?

That the undergraduates insulted any professor who allowed women to compete for prizes?

That the women were stoned in the streets, and finally excluded from the medical school?

That in 1877 the British Medical Association declared women ineligible for membership?

That in 1881 the International Medical Congress excluded women from all but its “social and ceremonial meetings”?

That the Obstetrical Society refused to allow a woman’s name to appear on the title page of a pamphlet which she had written with her husband?

That according to a recent dispatch from London, many hospitals, since the outbreak of hostilities, have asked women to become resident physicians, and public authorities are daily endeavoring to obtain women as assistant medical officers and as school doctors?

This poem is in the public domain.

The universe breathed through my mouth

when I read the first chapter of patience.

I held the book away from my body

when the illustrations became life-like:

the kite flew over the grass, a child tumbled

down a hill and landed at the mouth of neon waters.

The fox curled into itself under the tree

and an eagle parted the sky like the last curtains.

I found myself wandering the forest, revising

the stories as I worked the heavens.

I lived inside the candied house

and hung the doors with sweetness.

I devoured the windows and I was greedy.

With all this sugar, I still felt trapped.

I sought to change the moral

so I filled my baskets daily with strawberry,

thorn, and vine, piled my home

with pastries and the charge of regret.

I placed those regrets inside the oven

and watched the pie rise. I wanted

everything in the pie and yearned

all the discarded ingredients.

I kept myself in the kitchen for years.

Everything up in smoke and yet my apron

was pristine, my hair done just right.

You can say it was perfection, a vision

from the past, waving a whisk through a bowl

as if it were a pitchfork. When I left the house

made of confection, that’s when I began to live,

for everything I gave up was in that house.

I remember you there. Your fingerprints vaguely

visible in the layer of flour on the table.

Copyright © 2020 Tina Chang. This poem was co-commissioned by the Academy of American Poets and the New York Philharmonic as part of the Project 19 initiative.

Seraph Young Ford, Maryland, 1887

First woman to vote in Utah and the modern nation, February 14, 1870.

I am known, if at all, for a moment’s

pride: first American woman

in the modern nation

to vote though at the time

I wasn’t considered American

by all. Not modern, either,

but Mormon, one

the East Coast suffragists had hoped

would vote Utah’s scourge of polygamy

out. But plural marriage

was on no ballot

I ever saw. Why would it be,

my mother asked, when men

make laws and shape

their women’s choice in freedoms?

And how changeable

those freedoms are

denied or given

certain women, she knew, who saw

a Shoshone woman one day selling ponies

from a stall: watched, amazed,

her pocket all the earnings

without a husband’s permission.

I wouldn’t be a white girl

for all the horses

in the world, the woman scoffed

at her astonishment: my mother

who never sold an apple

without my father’s

say-so. Like my mother,

I married young, to an older man who believed—

like certain, stiff-backed politicians—

to join the union, Utah

must acculturate, scrub off

the oddities and freedoms

of its difference, renounce

some part of politics and faith:

our secrecy and marriage customs,

and then my woman’s right to vote. All gone

to make us join

the “modern” state—

And so perhaps I might be known

for what I’ve lost: a right, a home,

and now my mother, who died

the year we moved back East.

How fragile, indeed, are rights

and hopes, how unstable the powers

to which we grow attached.

My husband now can barely leave his bed.

As he’s grown ill, I’ve watched myself

become the wife

of many men, as all men in the end

become husband

to a congregation of women.

When he dies, I’ll move back West

to where my mother’s buried

and buy some land with the money

that she left—

To me alone she wrote,

who loved me,

and so for love of her

I’ll buy a house

and marble headstone

and fill my land with horses.

Copyright © 2020 Paisley Rekdal. This poem was co-commissioned by the Academy of American Poets and the New York Philharmonic as part of the Project 19 initiative.