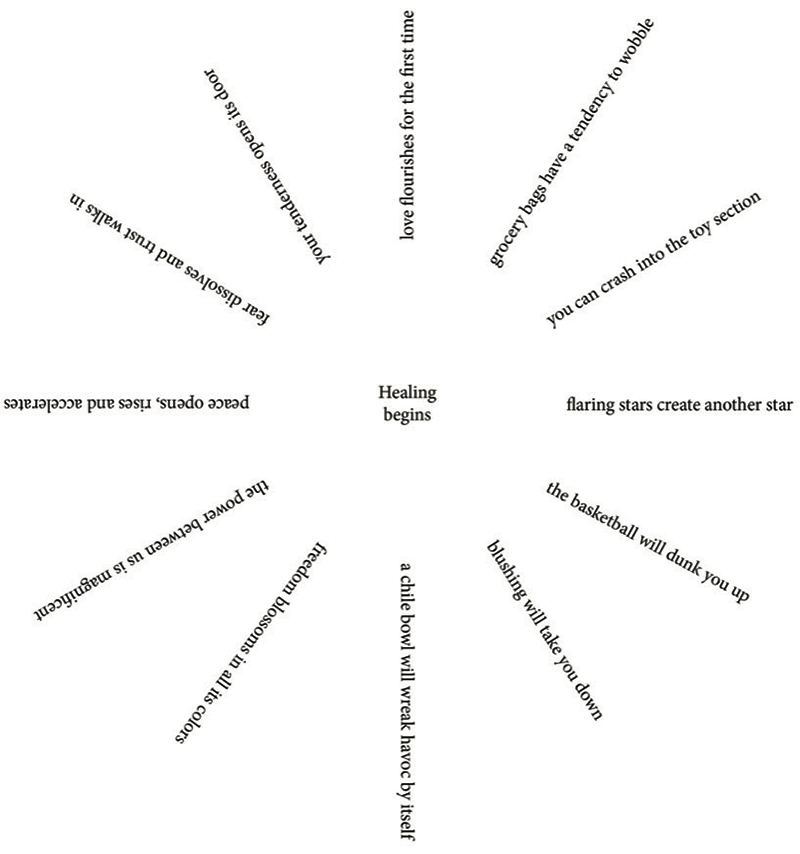

with design by Anthony Cody

Copyright © 2020 by Juan Felipe Herrera. Design by Anthony Cody. Originally published with the Shelter in Poems initiative on poets.org.

Copper and ginger, the plentiful

mass of it bound, half loosed, and

bound again in lavish

disregard as though such heaping up

were a thing indifferent, surfeit from

the table of the gods, who do

not give a thought to fairness, no,

who throw their bounty in a single

lap. The chipped enamel—blue—on her nails.

The lashes sticky with sunlight. You would

swear she hadn’t a thought in her head

except for her buttermilk waffle and

its just proportion of jam. But while

she laughs and chews, half singing

with the lyrics on the radio, half

shrugging out of her bathrobe in the

kitchen warmth, she doesn’t quite

complete the last part, one of the

sleeves—as though, you’d swear, she

couldn’t be bothered—still covers

her arm. Which means you do not

see the cuts. Girls of an age—

fifteen for example—still bearing

the traces of when-they-were-

new, of when-the-breasts-had-not-

been-thought-of, when-the-troublesome-

cleft-was-smooth, are anchored

on a faultline, it’s a wonder they

survive at all. This ginger-haired

darling isn’t one of my own, if

own is ever the way to put it, but

I’ve known her since her heart could still

be seen at work beneath

the fontanelles. Her skin

was almost otherworldly, touch

so silken it seemed another kind

of sight, a subtler

boundary than obtains for all

the rest of us, though ordinary

mortals bear some remnant too,

consider the loved one’s fine-

grained inner arm. And so

it’s there, from wrist to

elbow, that she cuts. She takes

her scissors to that perfect page, she’s good,

she isn’t stupid, she can see that we

who are children of plenty have no

excuse for suffering we

should be ashamed and so she is

and so she has produced this many-

layered hieroglyphic, channels

raw, half healed, reopened

before the healing gains momentum, she

has taken for her copy-text the very

cogs and wheels of time. And as for

her other body, says the plainsong

on the morning news, the hole

in the ozone, the fish in the sea,

you were thinking what exactly? You

were thinking a comfortable

breakfast would help? I think

I thought we’d deal with that tomorrow.

Then you’ll have to think again.

From Prodigal: New and Selected Poems, 1976–2014 (Mariner Books, 2015). Copyright © 2015 by Linda Gregerson. Used with permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

It was like this:

you were happy, then you were sad,

then happy again, then not.

It went on.

You were innocent or you were guilty.

Actions were taken, or not.

At times you spoke, at other times you were silent.

Mostly, it seems you were silent—what could you say?

Now it is almost over.

Like a lover, your life bends down and kisses your life.

It does this not in forgiveness—

between you, there is nothing to forgive—

but with the simple nod of a baker at the moment

he sees the bread is finished with transformation.

Eating, too, is a thing now only for others.

It doesn’t matter what they will make of you

or your days: they will be wrong,

they will miss the wrong woman, miss the wrong man,

all the stories they tell will be tales of their own invention.

Your story was this: you were happy, then you were sad,

you slept, you awakened.

Sometimes you ate roasted chestnuts, sometimes persimmons.

—2002

Originally published in After (HarperCollins, 2006); all rights reserved. Copyright © by Jane Hirshfield. Reprinted with the permission of the author.