To celebrate National Poetry Month 2017, we asked teachers to share how they teach poetry in the classroom. Here are some of their responses.

My favorite way to teach poetry is through a poem a day. I read a poem aloud, or a student does, or we watch a video of a spoken word performance. Then we discuss it, based of the students' thoughts. I do not prepare questions. I do not make them parse the poetry. We simply enjoy it. By the end of the year, my high school students often remark that they realize they like and understand poetry for the first time in their lives. I want to teach them to read poetry, not just to analyze it.

—Tracy Adrian, High School Teacher

Guatemala City, Guatemala

My favorite way to get my middle school students involved in poetry is to get them to write about something specific. I cut out pictures from books and magazines and glue them to blank 3x5 cards. I have the students bring pictures a day ahead of the lesson, and I glue some of these to cards as well. Each student then draws a card; I find there are better results if they chose something that appeals to them, rather than drawing randomly. Then we ask questions about the pictures: Who or what is pictured, where are they, what are they doing, where are they going, what have they done? What is the object, what is it used for, how it is ordinary or surprising, what does it remind you of? Sometimes the students ask different questions about colors or seasons in the picture or why the picture was taken.

After we have talked about the pictures as a class, my students have time to write something in response. The following day, they can expand upon what they wrote and make it into a poem. I ask them to keep it specific, using words that would make you see the picture if you didn’t have it before you, or would make you feel what the picture represents. For me, the hardest part of teaching is getting my students to make connections and see things and people as unique. With photos they have something concrete to begin with. Even though sometimes they end up writing about something completely different, the photo is a place for their imaginations to start a journey.

Also, it’s possible to get poetry from preschoolers by asking them to tell you the best, most wonderful secret they know! You have to be excited about hearing what they say and quick to write it down after, but little kids love secrets and made up stories and are glad to tell you all about them!

—Sharron Crowson, Retired Teacher

Seabrook, Texas

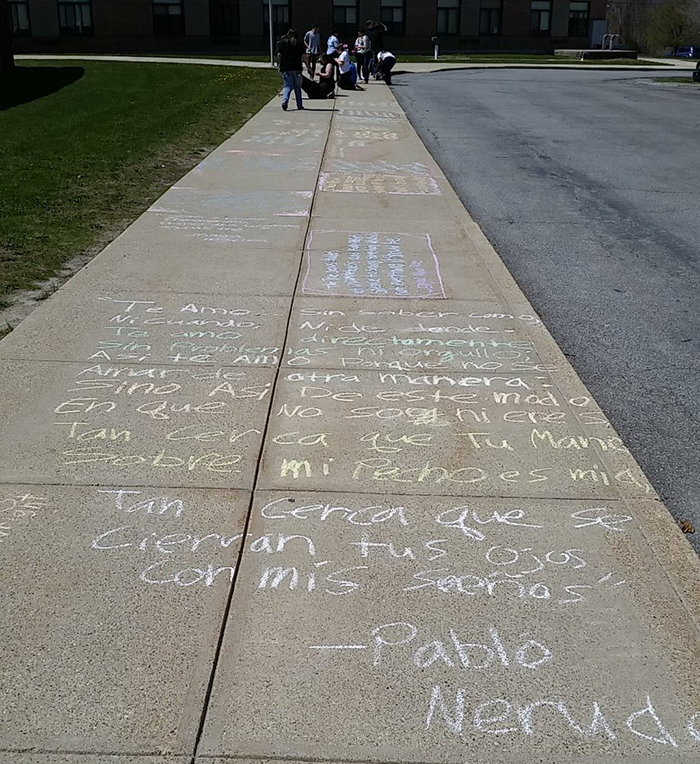

My favorite poetry activity is what I do to kick off National Poetry Month every year: sidewalk poetry. After stockpiling sidewalk chalk throughout the year, I take all of my classes outside to record poetry on the sidewalk. For homework, I ask them to visit Poets.org to look for poetry that speaks to them; all lines need to be approved since our building houses grades 4-12. I've been doing this for many years now, and the kids get so excited that they start asking in March if we're going to do it again this year. Older students I no longer teach also ask if they can come outside on their free periods to help out.

—Sherry Fisher, High School Teacher

Amenia, New York

My primary goal for the following activity is to alleviate any fear of poetry or the writing process. This activity works well with elementary through high school students, as each step unfolds differently for various ages once the students engage. First, I ask students to raise their hands and self-select into one of the following groups: a) don't like poetry; b) can take it or leave it; c) like it and/or even read or write it on their own. Then, I ask one or two students from each group why they feel as they do. They are inevitably clear and honest.

I share a poem with them, asking them first what the poem says literally, so we reach a general agreement on the "plot." Then, I ask them what else is going on in the poem and why they think so, which typically leads to diverse perspectives. Among my favorite poems for this step are Jack Hirschman's translation of Roque Dalton's "Like You," which works with any age; Jack Gilbert's "Failing and Flying," which is better with older students; and Naomi Shihab Nye's "Famous," among many other poems.

Building on the perspectives that emerge, we talk briefly about our unique human ability to change points of view. This leads to a writing prompt, which I structure as a free write or a draft; the only way to get it 'wrong' is to not write. The prompt invites the students to become something else, and write in first person from its perspective. Depending on age and ability I will offer them some possibilities or let them choose. Some that consistently work well are: your toothbrush (emphasis on "your"), a snowflake in a blizzard, a computer keyboard, the last leaf on a tree in autumn, a sock, a grain of sand in the desert, a traffic light, and a television screen.

—Reggie Marra, Teaching Artist

Danbury, Connecticut

I distribute a poem folded up from the bottom so that only its title is visible. I ask students to speculate on the title, making notes right on the paper, for three minutes or so. I call on each student to tell us her thoughts about the title. Then, I allow the students to adjust the folded paper so as to reveal only the first stanza or section of the poem.

I tell the class, "If you just report on the subject of the poem, you will likely summarize the work and/or paraphrase the speaker. But if you explain what you learn about the speaker, you will analyze the poem." I then ask my students to take notes and discuss the following questions about the first stanza or section: What are you learning about the speaker from what the speaker says about the subject of the poem? And how are you learning this? What's weird about the stanza? What is the effect of that oddity on you? What does it make you think or feel about the speaker who uttered it?

Once the discussion has exhausted the opening lines, I invite students to unfurl in turn each of the subsequent stanzas or sections (never fewer than three nor more than five sections). As they move through the text, they take notes on what has changed about the poem and the speaker. Ultimately, we discern what happens to the speaker—to her perceptions, emotions, realizations, understanding, and misunderstanding—over the course of the entire poem.

—James Penha, Retired Teacher

Jakarta, Indonesia

I saw middle and high school students most excited about poetry when they were invited to perform it. I divided the class into small groups, provided an abundance of poetry anthologies, and invited each group to choose a poem to perform. Their performance needed to include every member of the group, and every word of the poem, spoken (or sung) with clear enunciation and expression, consistent with the poem itself. Beyond that, my students were free to decide how to use their voices: word by word, they had to choose how many voices, what tone of voice, pitch, pace, and volume, where and how to add emphasis. They could opt to add simple gestures or movement, and decide how to define their performance space within the classroom, but no props were allowed: the power of the poem had to come from their delivery of the poet's words. They had time over several days to "script" their copies of the poem and rehearse. Participation was never an issue, as even shy students found their own comfort level as part of the "scripting" process (some taking solo parts, others sticking to "chorus" words or lines). I was always bowled over by their creativity.

For the best results, of course, students need a demonstration. We also read poems aloud, and I regularly worked with the whole class to script and perform a short poem or two as a "speak chorus," a term I did not invent: I first heard it from drama teacher Harriet Worrell at Woodstock Union High School in Vermont. That term helps students grasp how their impact comes from the harmonious work of the whole group, not from individual would-be "stars." Sometimes my seventh-graders would create a poem together and then "script" it to read as a "speak chorus." I would invite each student to choose three "golden lines" from their assigned journal entries, and I used at least one from every student, interwoven with lines from a traditional song, to create a poem they scripted and performed as a "speak chorus" at the end-of-the-year assembly. By this time, my students had had many opportunities to perform poetry, including their own, and this performance before the whole school was polished and powerful.

—Janice Prindle, Retired Teacher

South Woodstock, Vermont