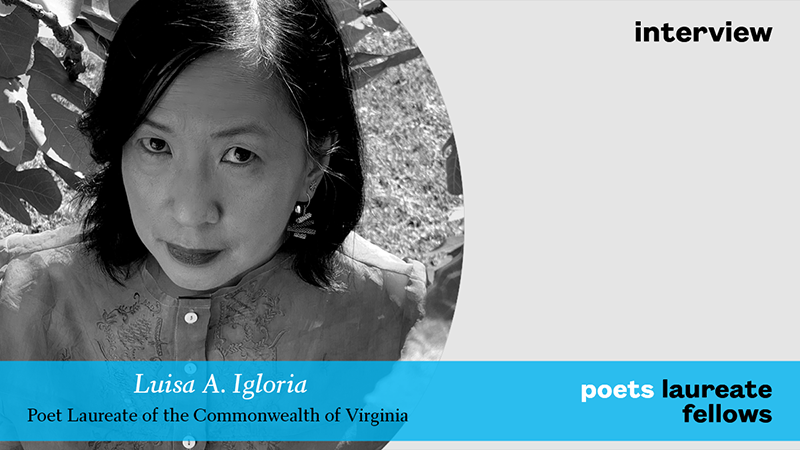

Luisa A. Igloria, poet laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, is the author of Maps for Migrants and Ghosts (Southern Illinois University Press, 2020) and teaches in the MFA Creative Writing Program at Old Dominion University. In 2021, Igloria plans to update and expand available public information on Virginian poets, in order to more accurately reflect the diversity of poets in this region, including youth poets, poets in the schools, poets in community-writing centers, immigrant poets, poets with disabilities, BIPOC, LGBTQIA poets, and poets in other (nonliterary) professions. The fellowship will also support a linked series of virtual poetry features and workshops on themes, including, but not limited to, civic engagement, social justice, mental health, community and care, climate change, and imagining the future. Finally, Igloria will launch a Young Poets in the Community program through which young poets in middle school and high school will propose poetry-focused programs or projects.

Poets.org: What do you hope for the future of poetry in Virginia? What support do you hope future poets laureate have?

LI: Prior to English colonization, Virginia was home to Indigenous Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan peoples. In the early 1600s, Jamestown became the first English settlement in North America. Tourists visit the fort site and reconstructed glasshouse, and watch historical interpreters walk around Colonial Williamsburg in period costumes. To this day, Virginia is connected to such narratives of American formation, conflict, and cultivation—but, it seems people know more about Civil War battles, Pocahontas, Virginia tobacco, or “Virginia is for Lovers” than about Virginia poets.

There are so many poets from diverse communities, so I hope the work we continue to do on the ground makes our contributions more widely visible. Our stories are important to the understanding of history and the efforts we make toward a more just and viable future.

The statewide organization that supports poetry is the Poetry Society of Virginia; in fact, it collects nominations at large for state poet laureate and recommends a shortlist, which is then forwarded to the governor’s office for selection and appointment. As an immigrant, a woman, and a poet of color, I’m proud to be the fourth poet laureate of color in Virginia (Rita Dove led the way, and then there are Sofia Starnes and Tim Seibles ahead of me). I hope the choice of future poets laureate will better reflect the increasing diversity of Virginia communities. For my FilAm community, there isn’t as much awareness as there could be about those of us who are writers, artists, and creatives.

I’ve had the good luck to receive one of twenty-three Poet Laureate Fellowships in 2021, and it’s made a real difference in my ability to carry out public poetry projects— especially since the Virginia poet laureate position has never come with any honorarium or stipend. I wish there were a bit more uniformity in the way appointed poets laureate of counties, cities, and states are given this kind of recognition and support. Also, while the position of poet laureate is described as honorary and we’re told that one need not even write anything while holding that office, it just seems to naturally go with the message that poetry, literature, and the arts have an important role in public life.

Poets.org: Has being a poet laureate changed your relationship to your own writing in any way?

LI: I have a daily writing practice that I’ve kept up for more than eleven years to date. Through this practice, what I’ve learned of myself and my writing is that poetry is my preferred way of “processing” all the information life throws at me. Becoming poet laureate hasn’t changed this. But, if anything, I think it’s made me feel both more intentional and more creative about the ways in which I’m able to share my writing with others.

Poets.org: What part of your project were you most excited about?

LI: I was very excited about creating opportunities for young poets across the state, as well as taking concrete steps toward making the idea of a Virginia Poets’ Database a reality. I’m grateful for the support of the Poetry Society of Virginia, especially for the former project, and Old Dominion University and its Digital Commons platform for the latter. When you’re appointed laureate, it can be overwhelming to realize that you’re the recipient of such a great amount of trust. And so, I remember saying, I may be poet laureate, but I can only do so much by myself. It takes a community, many communities, to carry out a vision.

Poets.org: What obstacles, if any, did you experience with your project?

LI: Many obstacles we encounter are logistical in nature. That’s certainly true for my projects. Finding creative solutions means reaching out and listening to others’ ideas, being willing to work as a collaborator, learning about what other creatives and thinkers are already doing; looking at existing resources to see how they could be shared for a common goal. I’ve learned even more that there’s nothing wrong with floating an idea or asking what others think, and I’ve met so many new people from doing so.

Poets.org: Congratulations on announcing the first cohort of Virginia Young Poets in the Community in December! We are thrilled for these young writers and inspired by them. The students were asked to complete their proposed projects between December 2021 and June 30, 2022. Can you tell us about some of those young poets' projects? Will some of their work be archived for future young poets and community members to access?

LI: Twenty-four young poets from across the state were selected for this first cohort of Young Poets in the Community and their projects are all unique. All of them have been asked to document their projects as they are carried out to completion, and my plan is to feature each of them on my website. These are only some of the projects:

One of the elementary school winners, David Babbick, will host a poetry podcast in which he’ll pair an older or more experienced poet with a young poet or student in the schools, and they’ll read as well as talk about how they can use poetry to make a difference in their community. Another elementary school poet, Emily Nguyen, is creating a “Poetry Path” on her school grounds; she will have students read Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem “The Blue Bucket,” and they will write poems about what fills up their own bucket. Key’Niyah Clemons, who is in middle school, says she loves her community and wants to give them a space to release and celebrate in a creative way, and so she will invite folks to come together to create a poetry collage on the 112’ x 25’ brick wall at her school. Another middle school poet, Elaine Zhang, will coordinate with her local library to hold workshops with students, and together they will write “poetry remixes” based on prominent poems centering on identity. Zoe Lee’s project aims to create poetry-reading and writing groups focused on themes like bullying, poverty, and inequality. One of our high school poets, Renee Anderson, has just completed her project and met her target of releasing it in February for Black History Month: she created a literary magazine called Black Dragon, and invited students from her school to contribute works highlighting themes of Black identity, Black culture, the roles and lives of people within the Black community, and more. Yayra McGodfred is looking to partner with groups like NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Coastal Virginia to create a poetry writing group for mental health awareness in May. Leia Morrissey aims to create an anthology she is calling “By the People, For the People.” Interested students from her school will meet regularly to write poems about problems they face both in school and their community—problems as simple as the lack of soap in bathrooms to more complex problems like the lack of environmental protection programs in the city. With her group, she aims to present these poems to the school board, the city council, and other relevant institutions that have the ability to enact change. Yunseo Chung wants to collect poems that chronicle the experiences of members of her community with COVID-19. Charlotte Maleski will work with school mentors and members of her school’s Students Against Sexual Assault Club to explore poetry and writing as ways to foster grounding. Virginia Kane will create a poetry workshop space for LGBTQIA+ teen writers, guided by a detailed syllabus focusing on four themes: origins, identity, the body, and community. Areen Syed intends to create a buddy program pairing local Hampton Roads high school students with refugee children who are interested in language arts; her goal is to encourage the use of poetry as a means of storytelling and forming friendships

Poets.org: You also launched a series of virtual events and workshops, on a variety of themes, including social justice, mental health, and community and care. How can a poet, or poetry, bring a community together?

LI: Every poem carries the seed of a story. And like music, it’s able to get to the emotional heart of an experience, sometimes even before we grasp the idea of it. It’s that capacity for opening up and listening more deeply to the world around us that poetry offers. Poetry is powerful this way because it asks us to really pay attention to the world. I think poems can convey some of our deepest feelings in images, in language that shows rather than masks. The sense of communing with others, which is at the root of the idea of community, is when we feel we can talk to each other about our joys, our doubts, our fears, our hopes—in the same way, perhaps, in which a poem talks to us and invites us in.

Poets.org: Is there a specific poem on Poets.org that inspires you and your work in Virginia, especially when it comes to empowering young writers in the community?

LI: Maybe it’s because I love figs; or because we have a little fig tree in our back yard which gives us a lot of pleasure in the summer and a lot of fruit that we love to share with friends because we couldn’t eat all of what it produces ourselves. But, I’ve always loved Ross Gay’s “To the Fig Tree on 9th and Christian” because of the way the poem leads every single reader and every person in the poem directly beneath the “canopy / of a fig its / arms pulling the / September sun to it” —and, all of a sudden, the tree becomes this improbable cornucopia, spilling delicious sweetness in the middle of Philadelphia. The tree is bursting with fruit. The bees are positively stoned with its sugar. The woman with the broom, the bald man rubbing his tummy, and eight or nine other people, gladly open their hands. There’s more than enough for everyone, but they’re “eating out of each other’s hands / […] feeding each other / from a tree / at the corner of Christian and 9th/ strangers maybe / never again.” The fig tree is generous, like poetry.