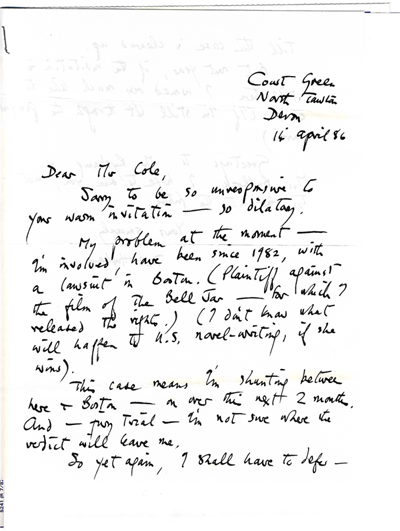

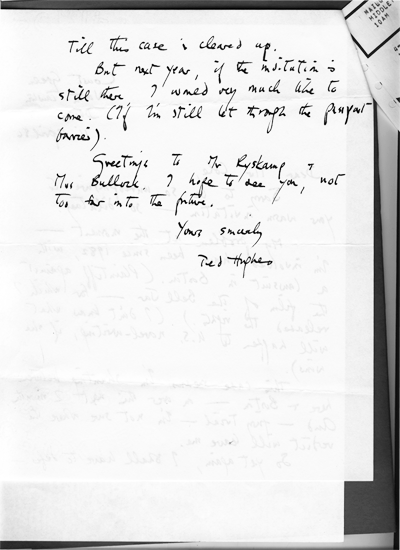

In this 1986 letter from our archive, Ted Hughes recounts the troubles he’s encountering due to a lawsuit involving a film version of The Bell Jar, the acclaimed novel written by his late wife, Sylvia Plath.

Plath first published The Bell Jar in 1963 under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas. Critics enjoyed the story of the descent of her protagonist, Esther Greenwood, and it later became known as a feminist classic. The New York Times Book Review called it “a fine novel, as bitter and remorseless as her last poems.” By 1966, the novel had been published in England under Plath’s real name, and five years later The Bell Jar made it to U.S. bookstores. Unfortunately, Plath did not get to enjoy the success of her novel; she died by suicide on February 11, 1963, less than one month after the book’s publication.

In the mid-seventies, Hughes, executor of Plath’s estate, sold the film rights to The Bell Jar. When Avco Embassy Pictures released The Bell Jar on March 21, 1979, critics panned the film for its performances and its deviations from the original plot and characters of the book.

On March 19, 1982, Jane Anderson, a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School and Plath’s acquaintance with whom she was hospitalized at McLean Psychiatric Hospital, filed a six-million-dollar defamation lawsuit against the filmmakers regarding the character of Joan Gilling. Anderson, who claimed Gilling was based on her, claimed the film falsely portrayed her as homosexual and as encouraging another person to engage in a suicide pact. Hughes was one of the sued parties and was the only one of the defendants to attend the trial itself—though, as he mentions in the letter, that involved a good deal of “shunting between [England] and Boston.”

The suit would not be settled for another nine months following the date of this letter; Anderson received a settlement of $150,000 and the defendants admitted that the film “unintentionally defamed” her. Hughes, however, did not need to fear how the ruling would affect “U.S. novel-writing,” a concern he mentions in the letter; Anderson said that only the portrayal of Joan Gilling in the movie was at issue in the case and Hughes would later say that the trial did not set up a precedent regarding the fictionalized portrayal of characters in novels.

Though clearly worried and wearied by the legal proceedings, Hughes was soon able to turn back to his own creative endeavors; he published Flowers and Insects (Faber & Faber) in October of that year and continued his responsibilities as England’s poet laureate, a post he was appointed to in 1984 and held until his death.

see more photographs and ephemera from the archive