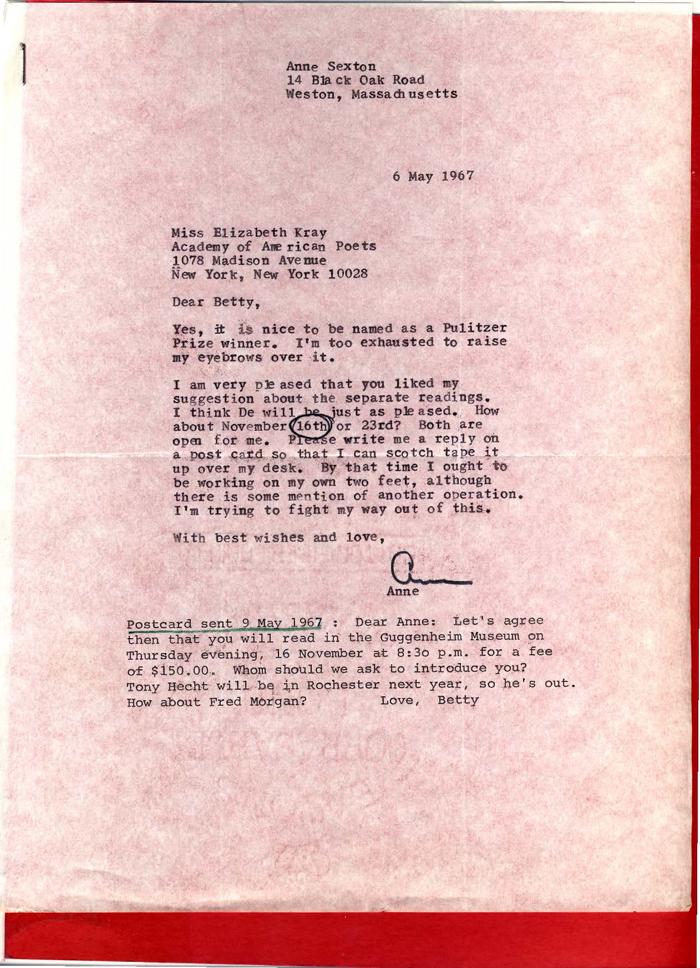

In this 1967 letter from our archive, recent Pulitzer Prize winner Anne Sexton writes to Betty Kray, the first executive director of the Academy of American Poets, about celebrating Sexton’s recent honor.

Sexton seems pleased and perhaps a bit overwhelmed at the news, as she had only just received the Shelley Memorial Award before also being named recipient of the Pulitzer Prize. In their previous exchange, in a letter written on May 2, Kray wrote to Sexton: “From now on, whatever else you do, you will be first tagged as a Pulitzer Prize winner. Do you remember when Frost used to raise his eyebrows over this?” In the letter, Kray goes on to say she will discuss the exciting news with a Claire “Cindy” Degener, who became Sexton’s agent at the Sterling Lord Agency in 1964 and was her close friend in the years to follow: “In a few moments I am going to call Cindy Degener and just hold the phone while she goes off like an air raid siren about your Pulitzer.” In this letter, Sexton herself responds to the honor, saying, “It is nice to be named as a Pulitzer Prize winner. I’m too exhausted to raise my eyebrows over it.”

Sexton was awarded the monumental prize for her celebrated collection Live or Die (Houghton Mifflin, 1966), a fictionalized memoir about her experiences with mental illness. The collection includes many of Sexton’s most popular poems, such as “Little Girl, My String Bean, My Lovely woman,” “Wanting to Die,” and “Sylvia’s Death.”

At the time the news was announced, Kray and Sexton had already been in conversation regarding a reading featuring Sexton and W. D. Snodgrass, the “De” mentioned in the letter. While Kray was originally planning for a joint reading between the two confessional poets, she soon changed her mind, because, as she wrote to Sexton, “both you and Dee are able to attract sufficient audience so that you don’t need the prop of another person. I have suggested the two of you because we have tried to make the joint reading a tradition which then takes care of the persons who cannot singly attract and audience.” That certainly would not have been a problem for either poet, as both poets were enjoying the popularity and acclaim of being named Pulitzer Prize winners at the time. (Snodgrass had received the award in 1960, for his first collection, Heart’s Needle.)

Kray’s response is included at the bottom of the letter, in which she confirms Sexton’s celebratory reading at the Guggenheim Museum on November 16, 1967.

In her letter Sexton mentions an injury that she hopes to overcome by the time of the reading later that year. In a letter she sent to her confidante, Lois Ames, from the Newton-Wellsley Hospital in November 1966, Sexton described how the injury came to be: “On my birthday … that day when one is supposed to be dead, the birth-night of the soul — Nov 9th — I tripped at the head of the gold carpeted stairs & fell & fell & fell & BROKE my hip — I can’t walk for a year. … am just today crawling out of the ‘pain machine’ (I call it). I kept yelling ‘Jesus! Jesus!’ and the nurse would shout back ‘Wrong name! I’m not Jesus. I’m Barbara’ — I guess I get blasphemous and religious all at once when I’m pushed to the rail.”

By the time she wrote her letter to Kray, it seems she was at least better off than she was when she wrote her November letter to Ames, and hopeful for her recovery: “By that time I ought to be working on my own two feet, although there is some mention of another operation.” Still, there is the hint of the ominous in her last sentence: “I’m trying to fight my way out of this.” While Sexton was simply referring to her hip injury, those familiar with the poet’s life may read some dark foreshadowing in the statement; despite a successful career that would include several subsequent books, Sexton would lose her battle with mental illness and commit suicide in 1974.