This archival document comes courtesy of Mademoiselle magazine, a now-defunct lifestyle magazine that advertised itself as “the magazine for smart young women.”

By 1953, the magazine’s circulation amounted to more than 500,000, and it was known for featuring both established writers (e.g., Truman Capote, William Faulkner, Dylan Thomas) and new writers, such as Sylvia Plath, who won the Mademoiselle Fiction Contest in 1952. The following year, she served as a guest editor and lived in Manhattan for a month, working on the August 1953 issue with the other young guest editors in the program. In the issue she wrote the following next to a photo of the guest editors standing in star formation: “Although horoscopes for our ultimate orbits aren’t yet in, we Guest Eds. are counting on a favorable forecast with this send-off from Mlle., the star of the campus.” She would later write a fictionalized account of her experiences that summer in her famous novel, The Bell Jar.

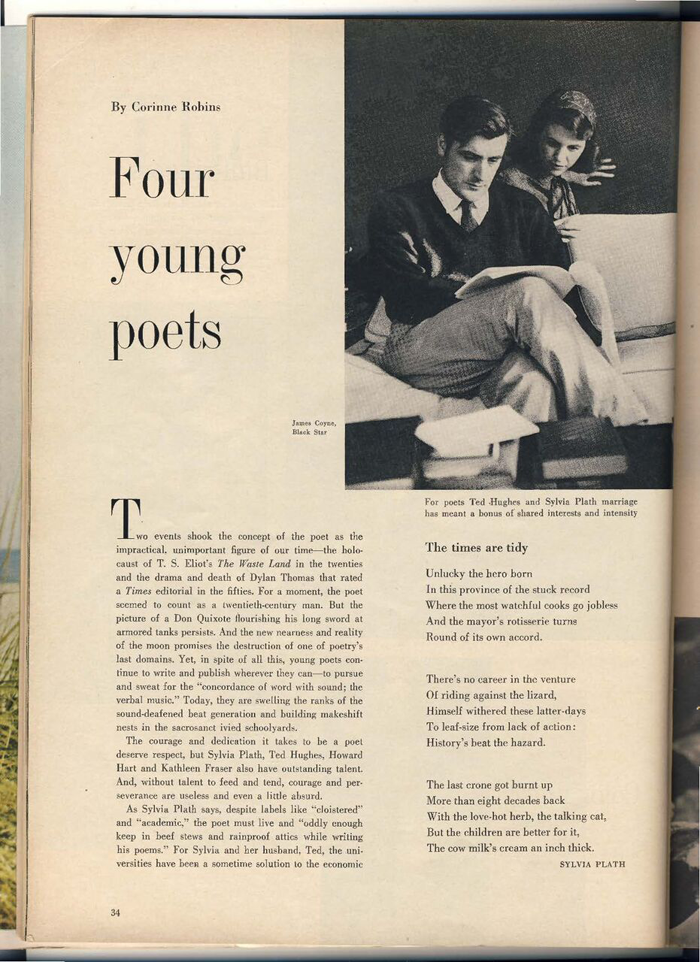

Though Plath’s time at Mademoiselle was relatively short, her name appeared in its pages once again six years later, in this January 1959 issue. Plath was featured—along with her poem “The Times are Tidy”—as part of the article “Four Young Poets.” Though Mademoiselle includes her recent publication credits and awards—which included, at the time, Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The Nation, and London Magazine, as well as the 1957 Bess Hokin Prize—her relationship with Ted Hughes, who she married in 1956, is featured with particular interest, with Plath subtly highlighted as both poet and—importantly—wife. In The Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Claire Brennan writes, “Returning from an English education with a handsome poet husband, Plath was the embodiment of Mademoiselle’s dreams and ambitions. Yet the accompanying photograph is rather telling; Hughes, darkly handsome and imposing, studies a book while Plath, crouched behind the chair, peers over his shoulder, appearing to be almost complementary. … Many feminist critics have returned to this dynamic, concerned with the difficulty of establishing oneself as a woman poet in the mid-century.”

Though Plath and Hughes had a rocky marriage that would end in separation three years after the printing of this article, here the article quotes Plath’s description of a picturesque domestic scene between the two poets: “The bonuses of any marriage—shared interests, projects, encouragement and creative criticism—are all intensified. Both of us want to write as much as possible, and we do. Ted likes a table he made in a window niche from two plants, and I have a fetish about my grandmother’s desk with an ivy and grape design burned into the wood. In the morning we have coffee (a concession to America) and in the afternoon, tea (a concession to England). That’s about the extent of our differences. We do criticize each other’s work, but we write poems that are as distinct and different as our fingerprints themselves must be.”

The year after this article was printed, Plath published her first collection of poems, Colossus. She then returned to England, where she gave birth to her children, Frieda and Nicholas, in 1960 and 1962, respectively. In 1962, Hughes left Plath for Assia Gutmann Wevill, and so began the start of a deep depression that would ultimately lead to her suicide on February 11, 1963.