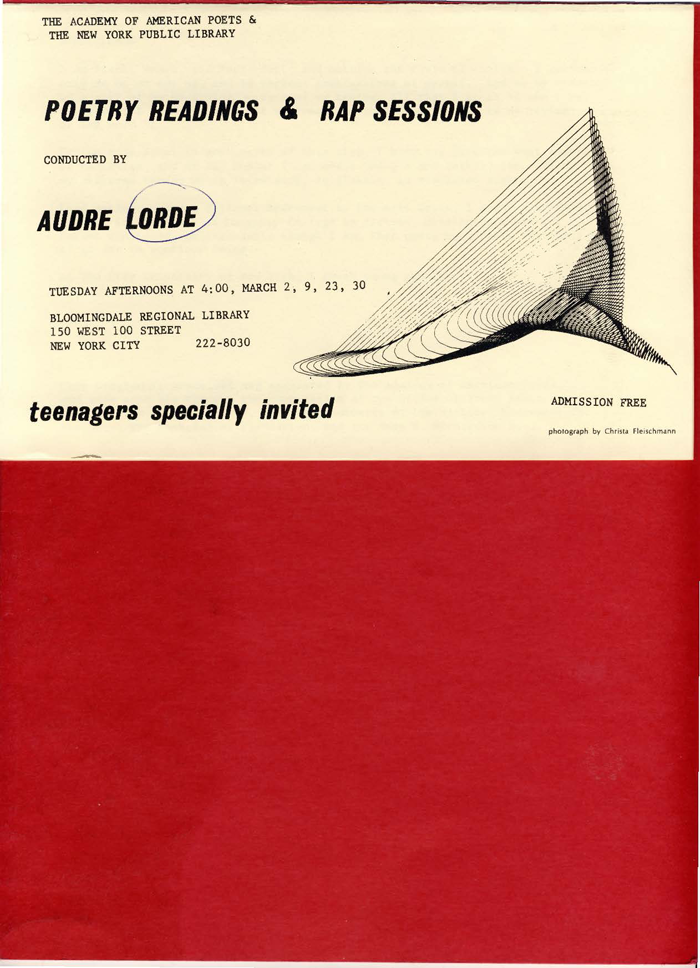

This document from the archive is a 1971 flyer for a series of readings and workshops featuring Audre Lorde and sponsored by the Academy of American Poets.

Betty Kray, then the executive director of the Academy of American Poets, reached out to Lorde in December 1970 to ask for her involvement in this new program. “The readings will attract a general audience, but the bulk would be ‘young adults,’ junior and senior high school aged kids,” Kray wrote in her letter. The program was also intended to educate students through poetry by writers of various backgrounds; as Kray wrote: “We are hoping to set up a series of programs, which would run for four weeks, one presenting contemporary Caribbean poetry and poetry by Puerto Ricans in New York, another presenting some contemporary black poetry, etc.”

Lorde responded that she was “delighted” to take part in the series, particularly because it presented an educational opportunity for young people. Lorde wrote back that January, “As a former young adult librarian, it has always given me great pleasure to work with this age group.”

Lorde herself was exposed to, and found a voice through, poetry as a teenager. She once said, “I was very inarticulate as a youngster. I couldn’t speak. I didn’t speak until I was five, in fact, not really, until I started reading and writing poetry. I used to speak in poetry. … I literally communicated through poetry. And when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry, and that was when I was twelve or thirteen.” It wasn’t soon after that, that Lorde published her first poem. It appeared in Seventeen magazine when she was just fifteen years old.

After receiving her MLS from Columbia University, Lorde served as a librarian in New York City public schools from 1961 to 1968, and in 1968, she published her first collection of poems, The First Cities (Poets Press). That year proved to be a turning point in Lorde’s life, as she also served as a writer in residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, where she discovered her love for teaching. “It was pivotal for me,” Lorde said. “Pivotal, because in 1968 my first book had just been published; it was my first trip into the deep South; it was the first time I had been away from the children. It was the first time I dealt with young Black students in a workshop situation. I came to realize that this was my work, that teaching and writing were inextricably combined, and it was there that I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

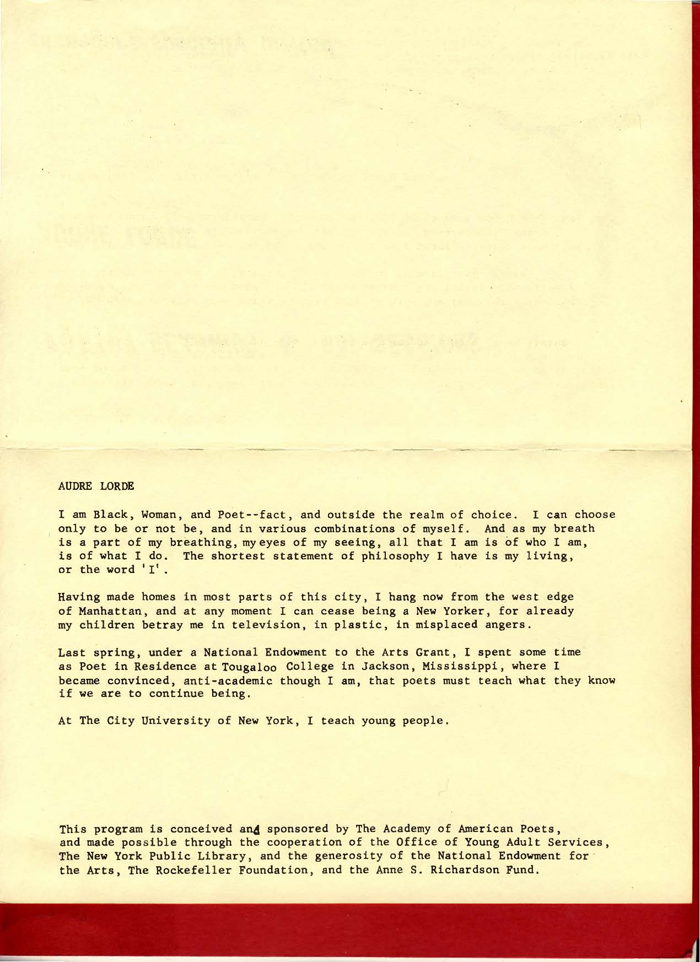

Indeed, in the biographical note on the flyer, Lorde says that Tougaloo is where she “became convinced, anti-academic though I am, that poets must teach what they know if we are to continue being.”

Lorde’s dedication to giving voice to marginalized groups and defining herself on her own terms is clear in the first few lines of this note: “I am Black, Woman, and Poet—fact, and outside the realm of choice. I can choose only to be or not be, and in various combinations of myself. And as my breath is a part of my breathing, my eyes of my seeing, all that I am is of who I am, is of what I do.”

In a 1979 interview, Lorde expounded on this statement: “I am not one piece of myself. I cannot be simply a Black person and not be a woman too, nor can I be a woman without being a lesbian. … Of course, there’ll always be people, and there have always been people in my life, who will come to me and say, ‘Well, here, define yourself as such and such,’ to the exclusion of the other pieces of myself. There is an injustice to self in doing this; it is an injustice to the women for whom I write. In fact, it is an injustice to everyone.”

Two years after Lorde conducted these workshops and readings, she published her third collection, From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press, 1973), which would be nominated for a National Book Award. Lorde would go on to publish several more collections of increasingly politicized and personal poetry and prose before her death in 1992.

“AUDRE LORDE

I am Black, Woman, and Poet—fact, and outside the realm of choice. I can choose only to be or not be, and in various combinations of myself. And as my breath is a part of my breathing, my eyes of my seeing, all that I am is of who I am, is of what I do. The shortest statement of philosophy I have is my living, or the word ‘I.’

Having made homes in most parts of this city, I hang now from the west edge of Manhattan, and at any moment I can cease being a New Yorker, for already my children betray me in television, in plastic, in misplaced angers.

Last spring, under a National Endowment to the Arts Grand, I spent some time as Poet in Residence at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, where I became convinced, anti-academic though I am, that poets must teach what they know if we are to continue being.

At the City University of New York, I teach young people.”