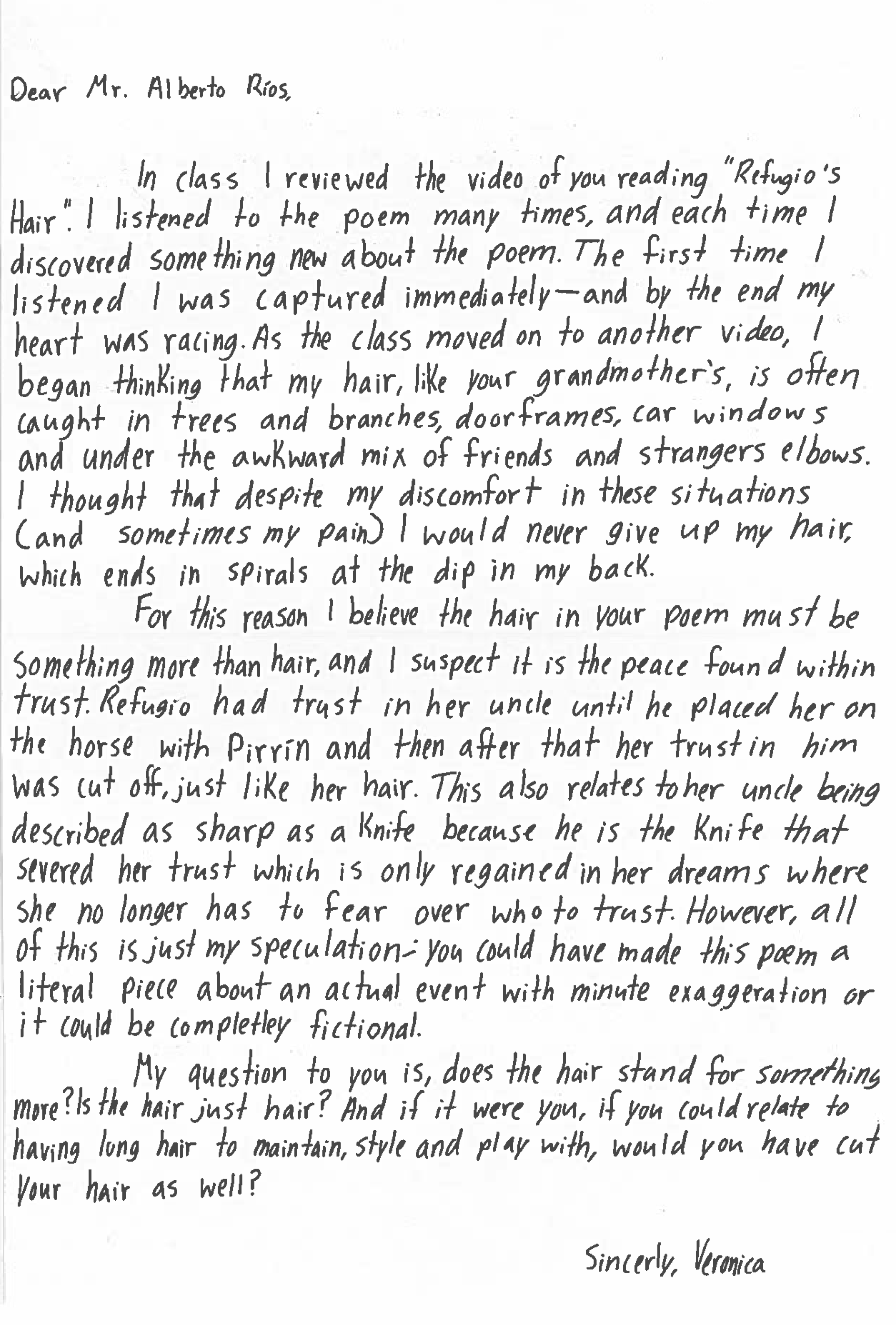

Dear Alberto Ríos,

In class I reviewed the video of you reading “Refugio’s Hair.” I listened to the poem many times, and each time I discovered something new about the poem. The first time I listened I was captured immediately—and by the end my heart was racing. As the class moved to another video, I began thinking that my hair, like your grandmother’s, is often caught in trees and branches, doorframes, car windows and under the awkward mix of friends’ and strangers’ elbows. I thought that despite my discomfort in these situations (and sometimes my pain) I would never give up my hair, which ends in spirals at the dip in my back.

For this reason I believe the hair in your poem must be something more than hair, and I suspect it is the peace found within trust. Refugio had trust in her uncle until he placed her on the horse with Pirrín and then after that her trust in him was cut off, just like her hair. This also relates to her uncle being described as sharp as a knife because he is the knife that severed her trust which is only regained in her dreams where she no longer has to fear over who to trust. However, all of this is just my speculation; you could have made this poem a literal piece about an actual event with minute exaggeration or it could be completely fictional.

My question to you is, does the hair stand for something more? Is the hair just hair? And if it were you, if you could relate to having long hair to maintain, style and play with, would you have cut your hair as well?

Sincerely,

Veronica

San Antonio, TX

Dear Veronica,

When you told me you learned something new each time you saw the video, I was very happy. That’s the greatest magic a poem can have, I think—to be different every time we read it, even though they’re the same words and it’s the same poem.

I love the story of your own hair—it made me think that you knew immediately how this could happen. It’s like your hair sometimes has a life of its own. I’m glad you’re happy with your hair. That might sound weird, but people aren’t always happy about different parts of themselves. I’m glad you have those curls of yours! I’m glad, too, that my grandmother had her hair when she needed it, as it literally saved their lives. Who knows what your hair will do?

And that leads to the magic, now, not of the poem, but as you so nicely understand, of the hair meaning more than hair. Yes! In this poem, it was so much more. Her hair wasn’t simply hair—it was whatever was inside my grandmother that would save that child no matter what. That it was the hair in this instance was simply, in a way, lucky for her, that she had something she could do, even if it was the hair itself moving into the branches. But I suspect she would have used or gone through anything to save the child. The hair, in that way, was her inner resolve, her inner will, to love.

Talking about my uncle and his sharpness—again, I think you are right onto it. The poem says that her sisters cut her hair to get them down from the tree, but Carlos had already cut something from her—trust, maybe. He had cut her in half by what he did. That sharpness was pure edge, and she had to choose which way to go. I am so glad she chose to be good in life—she was wonderful—instead of bitter. When we are hurt by someone, we have to choose what to make of that for ourselves.

And, hmmm, what would I do if I had long hair like that, given all the trouble involved in taking care of it? Well, I’m not sure, but I do know one thing: I would write about it!

Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts on the poem with me. I especially enjoyed your ideas about the hair. Please say hello to your teacher and classmates, and to your own family.

Sincerely,

Alberto