Look down fair moon.

Look down fair moon and bathe this scene,

Pour softly down night’s nimbus floods on faces ghastly, swollen, purple,

On the dead on their backs with arms toss’d wide,

Pour down your unstinted nimbus sacred moon.

1865

Reconciliation.

Word over all, beautiful as the sky,

Beautiful that war and all its deeds of carnage must in time be utterly lost,

That the hands of the sisters Death and Night incessantly softly wash again, and ever again, this soil’d world;

For my enemy is dead, a man divine as myself is dead,

I look where he lies white-faced and still in the coffin—I draw near,

Bend down and touch lightly with my lips the white face in the coffin.

1865–66

If you read through the collected shorter poems of Whitman—especially those brief lyrics in, say, Drum-Taps or Sandsat Seventy—you’ll notice that often Whitman will follow a poem in which he is not present with a poem on the same subject in which he is present. Call it a compulsion, it’s a delightful pattern as he rewrites his every impulse with himself at the center. The second poem I have given you here, “Reconciliation,” is a famous poem, but I like the first, not so famous, and clearly a lunar paraphrase of the second. Of course it was written first, and that makes the second a human paraphrase of the first. The faces in the first poem are purple, swollen, ghastly; the scene is obviously a battlefield, none of the corpses have been washed and put in a coffin as they are about to be in “Reconciliation.” And only then, after the moon has bathed them, does it occur to Whitman to kiss them. In fact, I think the moon is everywhere present in the second poem, though it is never mentioned. It’s there in the opening, “Word over all,” which of course refers to the title, “Reconciliation,” but is also mindful of “in the beginning was the Word,” which clearly, in the instance of these two poems, can be rendered, “First there was the moon.” And it’s present in the still, white face of the corpse itself, which Whitman kisses, and as he does so becomes the moon. I like to think of the second as a revision of the first, seen by the light of the moon, which has made the kiss, and the poem, possible. The moon making a poem possible... what can we say about that? What on earth can we say about poetry and the moon?

***

I am convinced that the first lyric poem was written at night, and that the moon was witness to the event and that the event was witness to the moon. For me, the moon has always been the very embodiment of lyric poetry. In the West, lyric poetry begins with a woman on an island in the seventh or sixth century BC, and I say now: lyric poetry begins with a woman on an island on a moonlit night, when the moon is nearing full or just the other side of it, or on the dot. Epic poetry was well established. The great men had sung of battles and heroes, whose actions affected thousands, and blinding shields and the wine-dark sea and the rosy-fingered dawn. Yet it is wrong to think that the clamor had died down. Historians tell us the times were not idyllic; in the Aeolian Islands, especially at Lesbos, the civilization was old but rapidly changing, torn by economic unrest and clashes between emerging political ideas and traditional principles. In the middle of all this then, a woman on an island on a moonlit night picks up some kind of writing instrument, or she doesn’t, she picks up a musical instrument, or she doesn’t, she begins to simply speak or sing, and the words express her personal feelings of the moment. Let’s call her Sappho. One can hardly say these little songs have survived—for we have only fragments—but even this seems fitting, for what is the moment but a fragment of greater time?

Tonight I've Watched

The moon and then

the Pleiades

go down

The night is now

half-gone; youth

goes; I am

in bed alone

There is a pervasive sorrow in the poem and not much struggle to change the order of things. The moon sets, the night passes, life flies, and the individual is the obvious repository of all this motion, insofar as she is aware of it, is conscious at all, and yet, lying alone in her bed she brings it at once to a standstill; the nauseous motion of the whole system is pinned and preserved like a butterfly upon a board, so that time hardly seems to be passing at all, though that is exactly what the poem is about. It has been noted many times that there are more sad poems than happy poems in this world, and though I have not fed them all into a computer and read the printout, I would guess that the moon occurs more frequently than the sun as an image in lyric poetry. And I wonder, why? I could start with a dozen reasons: insomnia; the moon’s association with death, one of poetry’s most common themes (yet the moon is equally associated with fertility); or the fact most of the poems in this world have supposedly been written by heterosexual men, who desire women, and the moon is embodied, in so many languages, as a woman, though that’s not universally true— German is one of the notable exceptions. One thing leads to another, one thing cancels another thing out, they are all interconnected, and none of them interest me. After all, it has been proved, using highly sensitive equipment, that even a cup of tea is subject to lunar tides. Let me offer a simple observation. There is a greater contrast between the moon and the night sky than there is between the sun and the daytime sky. And this contrast is more conducive to sorrow, which always separates or isolates itself, than it is to happiness, which always joins or blends. And to stand face-to-face with the sun is preposterous—it would blind you. Every child is taught not to stare at the sun. The sun is the source of life itself, the great creative power. One cannot confront god without instant annihilation; you can’t look directly at Medusa, but you can look at her useless reflection. The moon has no light of its own; our apprehension of it is but a reflection of the sun. And some believe artists reflect the creative powers of some original impulse too great to name. Another thing: the moon is the very image of silence—and, as Charles Simic says, “The highest levels of consciousness are wordless.” The great lunacy of most lyric poems is that they attempt to use words to convey what cannot be put into words. On the other hand, stars were the first text, the first instance of gabbiness; connecting the stars, making a pattern out of them, was the first story, sacred to storytellers. But the moon was the first poem, in the lyric sense, an entity complete in itself, recognizable at a glance, one that played upon the emotions so strongly that the context of time and place hardly seemed to matter. “Its power lies precisely in its remaining always on the verge of being ‘read,’” says Simic, speaking of photography, and I see the moon as the incunabulum of photography, as the first photograph, the first stilled moment, the first study in contrasts. Me here—you there. Now that’s an interesting map—only I’ve got it all wrong. As Paul Auster points out in his novel Moon Palace, it really goes like this—“You there—me here.” Land maps, the art of cartography, did not exist, could not exist, until after the astronomers flourished: “A man can’t know where he is on earth except in relation to the moon or a star. ... A here exists only in relationship to a there, not the other way around.” The there must come first. The moon is very clearly the Other—capital O, full moon O—in relationship to which we stand and exist. Every glance at the moon, in whatever phase, pinpoints our existence on earth. For the sky is the only phenomenon that can be seen from all points on the planet. All cultures, without exception, have an experience of the moon. If Ezra Pound claimed that all ages are contemporaneous, Simic says it is because all present moments certainly are. When I lived in China, the people I met were surprised that I made as much of the moon as they did. Apparently they believed the West did not sufficiently appreciate its qualities. Indeed, they have a whole holiday—the mid-autumn festival—given over to the moon. On the night of the full moon in September, families come together after dark and have an outdoor picnic, lit by those round lanterns that are in imitation of the moon, and they eat round food, including the round cakes baked for the occasion and known as mooncakes. The spectators stay put, even on a cloudy night, until the moon can be viewed, however briefly. The Chinese look at the moon and think of some family member or loved one who is not present, and know that on this same evening the absent one is reflecting on them. I myself sat in a circle of unmarried girls who passed the time imagining their unknown future husbands looking at the moon and imagining them. The lunar image became a form of communication, as indeed all imagery does in poetry: “The eye has knowledge the mind cannot share,” says Hayden Carruth.

Neruda, in his poem “Nocturnal Establishments,” calls himself a “surviving worshiper of the heavens”—which is what many poets are, I think, yet some say there are two things that call this into question: postmodern theory and technology (which are inseparable) and the Apollo Lunar Landing Missions. There’s a popular and interesting book just published on cyberspace—Being Digital by Nicholas Negroponte. Without dwelling too much on it—for my heart is really with the Apollo Lunar Landing Missions—I want to comment on a few remarks by Mr. Negroponte. “The digital planet will look and feel like the head of a pin.” Comment: with a thousand angels dancing there. Remark: “The slow human handling of most information in the form of books, magazines, newspapers, and videocassettes, is about to become the instantaneous and inexpensive transfer of electronic data that move at the speed of light.” Remark, by Keats, on first looking into Chapman’s Homer: “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken.” I imagine that could occur somewhat near the speed of light, along with all those red wheelbarrows and white chickens standing in the rain. Okay, three seconds—as the approximate duration of the present moment has been defined—not quite the speed of light, but about the time it takes to look at the moon. Really, people must think literary aficionados are all addicted to painfully heavy, slow things. Like the aircraft used for the lunar launches, good books only look heavy and slow: their speed depends on their internal engines and where they are pointed. The moon seems like an appropriate link between NASA and poetry. As Julio Cortázar put it: “Man has reached the moon, but twenty centuries ago a poet knew the enchantments that would make the moon come down to earth. Ultimately, what is the difference?” Last fall, a little article called “Poetry and the Moon, 1969” by Edward Lense appeared in the AWP Chronicle. Mr. Lense’s concerns are not really mine, but to put the article in a nutshell, Mr. Lense effectively uses the moon landing of July 20, 1969, as an exercise in semiotics, showing how in poetry images of the moon changed with the advent of technology. So that we go from the moon of myth—Robert Graves’s White Goddess, the muse, the rich gorgeous silvery stuff of Artemis or Diana—to the ambivalent postlanding stuff like Robert Lowell’s image of the moon as a dead “chassis orbiting about the earth, / grin of heatwave, spasm of stainless steel, / gadabout with heart of chalk, unnamable / void and cold thing in the universe.” The moon at midcentury gets hidden behind smog, gets imprisoned, entombed, finally reduced to ash, as if poets declared, says Mr. Lense, “that metaphoric language could no longer be used for the moon because it had become too prosaic once the astronauts had removed its mystery by landing on it.” That seems contradictory to me, since ash, smog, prison, and tombs, when used in relation to the moon, are metaphors, and though metaphors change, to say they are abandoned is in error. But I know—you know—what he means. Basically it’s like saying a woman is not interesting unless she’s a virgin. Lowell was too good a poet to believe this, so his lines actually resonate with some interest, but Mr. Lense also quotes at length and discusses seriously some really dreadful moon-verse written on the occasion of the first moon-landing and published the day after by the New York Times—in particular, poems by Babette Deutsch and Anthony Burgess (Mr. Lowell’s poem is not included in the Times), poems that are so bad I think it is unfair both to the poets themselves, who are not at their best in these occasional verses, and to the general reader, for whom the poems are used as an indicator of how poets responded to the moon landing and its aftereffects on the imagination. Mr. Lense could sensibly argue that a full-page spread of poetry in the New York Times is an indicator of something, and he would be right. In fact, the whole of that day’s newspaper, which I have read, is rather wonderful. On the front page there is a poem by Archibald MacLeish, a thoroughly mediocre poem that Mr. Lense also discusses and dismisses—it’s a vague, positive account and celebration of the moon landing, and includes the earnest, straight-faced line “O, a meaning!” and though MacLeish never says what that meaning is, I think the contrast between how such a line was read in 1969 and how it is read today is an even better indication of the changes that have taken place in poetry. And wasn’t it Mr. MacLeish who said, “A poem should not mean, but be”? And, in a remarkable aside that has nothing to do with the moon landing, there is printed on the Letters to the Editor page—without commentary—a poem by Mr. James Kirkup called “Emily in Winter: Amherst.” There is extensive coverage of the war in Vietnam and the unrest among students at home; and then there is the page Mr. Lense focuses on, a full-length spread of poems by Babette Deutsch, Anthony Burgess, Anne Sexton, and the Russian Andrei Voznesensky. These are the poets, he says, who level the charge of lunacide against NASA. Lunacide! That’s a wonderful word and I thank Mr. Lense for it. But the charge is suicidal. Last summer marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the moon landing, and I don’t think the moon has lost any of her presence. Mr. Lense closes his article with a paragraph beginning: “At the moment, then, the gods in heaven have lost their names, and adequate new names have yet to be invented by poets or anyone else.” I wish I had a dollar for every time I have heard that. I am reminded of what Kenzaburo Oe, the Japanese novelist, said recently at a symposium of Nobel Laureates in Atlanta: “It is the second job of literature to create myth. But its first job is to destroy that myth.” And, thinking of Mr. Lense’s use of the phrase “at the moment” (“At the moment, then, the gods in heaven have lost...”), I am reminded of what the great Italian poet of the twentieth century, Eugenio Montale, says in his poem “To Pio Rajna”: “He / who digs into the past would know / that barely a millionth of a second / divides the past from the future.” I think it is much more interesting—better things get said—to turn from the poetry pages of that old newspaper to the pages of moon-walk response, in the same issue, written in prose by various prominent people of the time. Pablo Picasso: “It means nothing to me. I have no opinion about it, and I don’t care.” With his moonlike head, alive in his own moment, Picasso struck a pose of isolation, cut off from the pressing issues of the day. What about the astronauts themselves? While they were on the moon, isn’t it likely there was at least one moment when they were cut off from the pressing matters of the day, their job, the rest of us on Earth—surely!—and fulfilled some private experience of wonder or fear or repose? One notable spoke as if he were an astronaut himself—Vladimir Nabokov: “Treading the soil of the moon, palpitating its pebbles, tasting the panic and splendor of the event, feeling in the pit of one’s stomach the separation from terra... these form the most romantic sensation an explorer has ever known... this is the only thing I can say about the matter... The utilitarian results do not interest me.” The uselessness of poetry rears its head, its basic nonutilitarian nature. But to inhabit the moment is not the exclusive domain of poetry. After all, Neil Armstrong had become a lunatic, literally, touched by the moon.

Between 1969 and 1972, six missions left for the moon and six missions came back. Not everyone who reads poetry is changed by the experience, nor were all the men who went to the moon forever altered by their vacation. But those who were, without exception, all say the same thing—it was not being on the moon that profoundly affected them as much as it was looking at the earth from the vantage point of the moon. The earth became the Other. You there—me here.

Alan Shepard, Apollo 14: “I remember being struck by the fact that it looks so peaceful from that distance, but remembering on the other hand all the confrontation going on all over that planet, and feeling a little sad that people on planet earth couldn’t see that same sight because obviously all the military and political differences become so insignificant seeing it from that distance.”

Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14: “For me, it was the beginning of unitary thinking. To think that the molecules of my body were manufactured in the same furnace as those stars in those galaxies billions of years ago.” Mitchell left NASA a year after his return and founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences in Northern California, an institution devoted to the study of consciousness, and of how we fit into the universe. In 1994 the institution had 40,000 members. “We went up there as space technicians, and we came back humanitarians. Looking [back] at earth is an instant global consciousness.”

James Irwin, Apollo 15: “I felt the power of God as I’d never felt it before.” Mr. Irwin, apparently, had an epiphany while on the moon—a year after his mission, he resigned from the Air Force to found the evangelical High Flight Foundation. He led several expeditions to Turkey’s Mt. Ararat in search of evidence of Noah’s Ark. He died of a heart attack in 1991, but not before writing this about the moon: “We lived on another world that was completely ‘ours’ for three days. It must have been very much like the feelings of Adam and Eve when the Earth was ‘theirs.’ How to describe it, how to describe it.”

Alan Bean, Apollo 12: “Every artist has the earth or their imaginations to inspire their paintings. I’ve got the earth and my imagination, and I’m the first to have the moon too.” Mr. Bean is a full-time painter. All he paints are pictures of the moon. “Certainly riding a rocket to the moon is the biggest kick you can have, but when I paint I get the same feeling that I got when I flew in space well. Certainly the view isn’t as good, but the best part of life is internal.”

Neil Armstrong, Apollo 11: There are no comments by Mr. Armstrong. He lives reclusively in Ohio and does not attend conferences, reunions, celebrations, parades, anniversaries, press events. He does not answer mail from strangers, answer the telephone, open the door. He was however, many years ago, asked how he felt knowing his footprints might remain undisturbed on the lunar surface for centuries. “I hope somebody goes up there some day,” he said, “and cleans them up.”

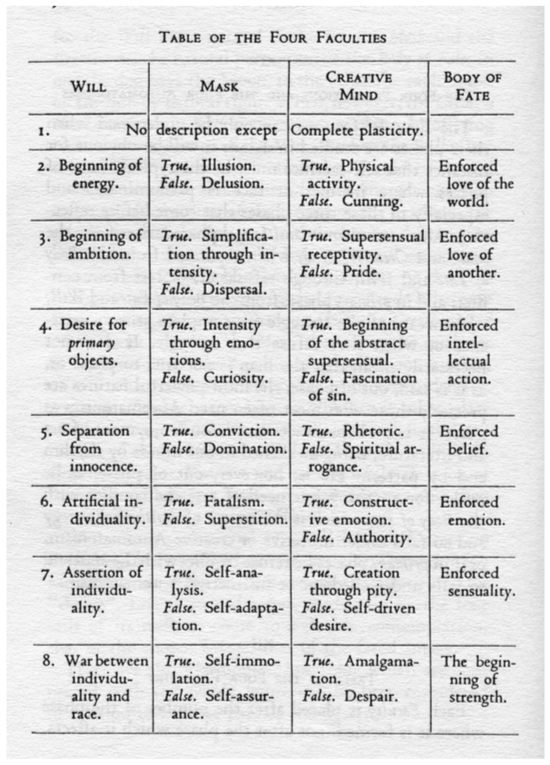

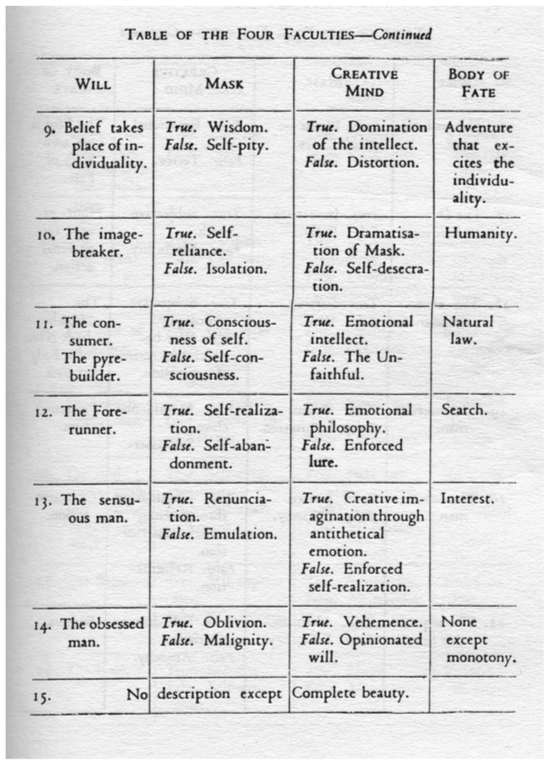

One thing is clear from these experiences: the men began with a mission—the Apollo Lunar Landing Mission, one that would affect, technologically, hundreds of thousands of lives through the development of computers, transistors, integrated circuits, and lightweight plastics—and ended with a vision. From mission to vision. Yeats would know exactly what this was all about. According to his ultimate moon-chart, he could have predicted it. When I was in college I read Yeats, and, of course, A Vision, that strange supernatural document that was given—spiritually dictated—to Yeats’s wife Georgie, beginning in 1917 and ending in 1920, in sessions of automatic writing, in which she became a medium for the unknown and unseen writer—actually a group of them—who later, so as not to fatigue her, came to her while she was asleep and spoke aloud through her while she was sleeping. When I look back at the book now and read some of the passages my nineteen-year-old hand underlined, I sometimes laugh out loud. I don’t trust such elaborate and complete systems, I don’t trust methods by which we categorize men and humanity, which is exactly what A Vision is, a system using the phases of the moon as its metaphor (“We have come to give you metaphors for poetry,” the voice said to Yeats), a system that constructs the history of consciousness, both individual and collective, in the past, present, and future. A system that could, say, forecast the birth, or death, of a Christ or a Nietzsche. According to this system, the universe is a great egg that turns itself inside out and then starts building its shell again. So you see, there is still much in A Vision that fascinates. I certainly don’t have the time here today to devote myself to discussing A Vision. I want only to speak briefly about two phases of the moon according to the chart.

I want to look briefly at phase one, the new moon, “no description except complete plasticity”; complete plasticity is complete objectivity, pure thought, and the character of the first phase is moral. And at phase fifteen, the full moon, “no description except that this is a phase of complete beauty”; complete beauty is complex subjectivity, pure image; the character of the fifteenth phase is physical. In other words, thought disappears into image and image disappears into thought. Yeats believed that every soul or person was eventually reincarnated into the first and fifteenth phases, which are both pure spirit without a bodily equivalent. Keats, in his lifetime as Keats, was born at phase fourteen, as close as one can come to pure image and still exist, a rather ideal phase for a lyric poet; Yeats calls him an almost perfect type where intellectual curiosity is, though still present, at its weakest, so you have the wonderful cusplike effect of thought and feeling in his work. As Yeats describes it, “The being has almost reached the end of that elaboration of itself which has for its climax an absorption in time.” A woman alone at night looking at the moon, and since her character is physical, let’s make her naked. But didn’t I say earlier that sorrow, the isolated sensuality of so much lyric poetry, seeks to separate itself from its surroundings? How then can it be absorbed into time? It seems that in the moment the final elaboration of oneself is made—when one finally asserts oneself—I am alive and I know it!—the moment expands to its full stature as eternity. Call it gibberish, this is what poetry is famous for. In fact when Yeats says “the being has almost reached the end of that elaboration of itself which has for its climax an absorption in time,” he is describing the birth of the lyric poem, that little bit of masturbation, which, if you look at the chart, inevitably had to be preceded by the plasticity, the thoughtful moral character of the great epic poems. But when I look at these charts I think more of Wallace Stevens than I do of Yeats. In Stevens, the sun is used as an image much more often than the moon is. His metaphors are different, but his “poles” are like the new and full moons, and he routinely strips and clothes himself. Clothe me for I am naked, says Yeats in most of his poems; Strip me for I am clothed, says Stevens in most of his. Indeed, the moon embodies the three principles of poetry as put forth by Stevens in his poem “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction”: (1) it must be abstract, as only the pure plasticity of a return to possibility can be abstract, the new moon as an “immaculate beginning,” the “original source of the first idea”; (2) it must change, the principle by which Nanzia Nunzio, on her trip around the world, loses her virginity; (3) it must give pleasure, thus poetry comes round like the moon to its “irrational // Distortion... the more than rational distortion, / The fiction that results from feeling,” and finds in its fullness a final good, though that “final” is part of its fiction.

There are societies on earth today whose inhabitants do not believe that man has walked on the moon. You might say they believe in a fiction, but that fiction constitutes their way of knowing things. Today I am surprised that, although I was a sentient being living in civilization, I recall very little about the first stroll on the moon, though I know exactly where I was when it happened. But I was not watching it on television and I do not recall what phase the moon was in—that kind of thing. I was in a Belgian taxicab around ten p.m. on that Sunday night in 1969 (had a poet been working at NASA perhaps it would have been scheduled for a Monday), I was on my way to a café—a bar really—where I met my friends for drinks every night of the summer. The driver spoke only Flemish and I only English. He was listening to the radio and suddenly he began to shout and speak rapidly. It took some time for it to register and then I remembered that right about now the Americans were supposed to land on the moon. He pulled over to the side of the road and got out of the cab. I got out too and there was the moon in the night sky—he pointed at it and I nodded and we stood there for a moment, in silence, looking at the moon. Then we got back in the cab and he drove me to the place I wanted most to be, though when I was there I would never admit to any of my friends that I spent the rest of my time alone in my room writing poetry. I even remember an image I was especially fond of in one of those poems—there was some woman wandering around a field carrying a strawberry wand! When I paid the driver his fare he pointed again at the moon and said a single word I didn’t understand. But one of my friends inside the bar spoke Flemish and later I asked him what it meant. He said it meant crazy. But no less an authority than the Dalai Lama tells us the moon to a Buddhist is representative of serenity and repose. Is Sappho’s poem, ultimately, one of agitation or repose? I’ll let Maurice Blanchot answer that: “Repose in light can be—tends to be—peace through light, light that appeases and gives peace; but repose in light is also repose—deprivation of all external help and impetus—so that nothing comes to disturb, or to pacify, the pure movement of the light. ... Repose in light: is it sweet appeasement through light? Is it the difficult deprivation of oneself and of all of one’s own movement, a position in the light without repose? Here two infinitely different experiences are separated by almost nothing.” I know it’s heavy-handed, but I think this is what happens when we look at the moon, and when we write: in each case, two infinitely different experiences are separated by almost nothing, and that very nothing is what is most essential and difficult to maintain. When Buzz Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface of the moon, his first words were: “Beautiful, beautiful. Magnificent desolation.”

"Poetry and the Moon" from Madness, Rack, and Honey. Copyright © 2012 by Mary Ruefle. Used with permission of the author and Wave Books.