In this 1935 letter from the archive, Robert Frost corresponds with Marie Bullock, founder of the Academy of American Poets, regarding America’s recognition of poets and artists of other disciplines.

Bullock, who had just founded the Academy of American Poets a few months prior to this letter, had reached out to Frost to tell him about the newly formed organization. She asked Frost to help her spread the story of the Academy of American Poets. In her letter she wrote:

"We are making such splendid headway with the increasing

confidence and backing of those who feel as we do: that

this project, through its nationwide activities and the

integrity of its purpose, will do much toward stimulating

an interest in and a demand for fine poetry through the

country.

We have radio programs planned to present poetry in a

new and compelling way to the American public,

awakening the hitherto rather dormant attitude toward

poets and their work.

Your moral approval of our project would be of utmost

value to us ..."

A few days later, Frost replied positively in his letter, in which he also mentions his wish for “a civil list for poets, musicians, and of artists here such as they have in England.” While Frost is nothing if not the quintessential American—particularly New England—poet, perhaps he was a bit endeared to England for this reason. In the early 1900s, when Frost was in his early 30s and in the early years of his marriage and family life, he struggled to gain success through poetry. Frost worked on his farm in Derry, New Hampshire, during the day and wrote poems at night, but for years publications rejected his work. After years of frustrated efforts, Frost sold the farm and moved with his family to England in 1912. Within a few months, Frost had found a publisher and would publish his first two books of poems, A Boy’s Will and North of Boston, there. “I was only too childishly happy in being allowed to make one for a moment in a company in which I hadn’t to be ashamed of writing verse,” Frost told the poet F. S. Flint in 1913. It was then, in England, that he finally began to receive the critical acclaim he would become known for. By the time Frost returned to America in 1915, editors were clamoring to publish him.

The “Phi Beta Kappa Eclogue” Frost mentions in his letter is the poem “Build Soil—A Political Pastoral,” which he delivered on May 31, 1932, at Columbia University. Inspired by Virgil’s “First Eclogue,” “Build Soil” discusses the poet in society—how politics and poetry may come together—as well as socialism and his take on the country’s involvement in foreign affairs.

The fact that Bullock asked for Frost's "moral approval" of the Academy and its programming is telling; though this organization was in its infancy at the time, Frost was at the peak of his career, known as the most celebrated poet in America. He had authored three books by the time of this letter, and his fourth, A Further Range (Henry Holt and Company, 1936), would appear the following year and would win him a Pulitzer Prize—his third of four in his lifetime.

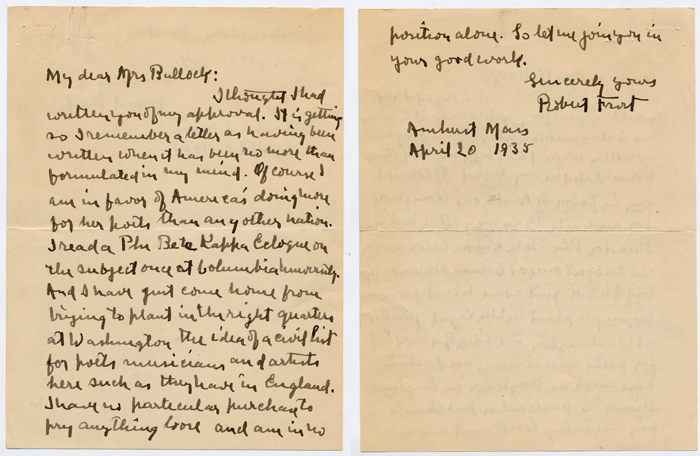

My dear Mrs. Bullock:

I thought I had written you of my approval. It is getting so I remember a letter as having been written when it has been no more than formulated in my mind. Of course I am in favor of America’s doing more for her poets than any other nation. I read a Phi Beta Kappa Eclogue on the subject once at Columbia University. And I have just come home from trying to plant in the right quarters at Washington the idea of a civil list for poets, musicians, and of artists here such as they have in England. I have no particular purchase to pry anything loose and am in no position alone. So let me join you in your good work.

Sincerely,

Robert Frost

Amherst Mass

April 20, 1935