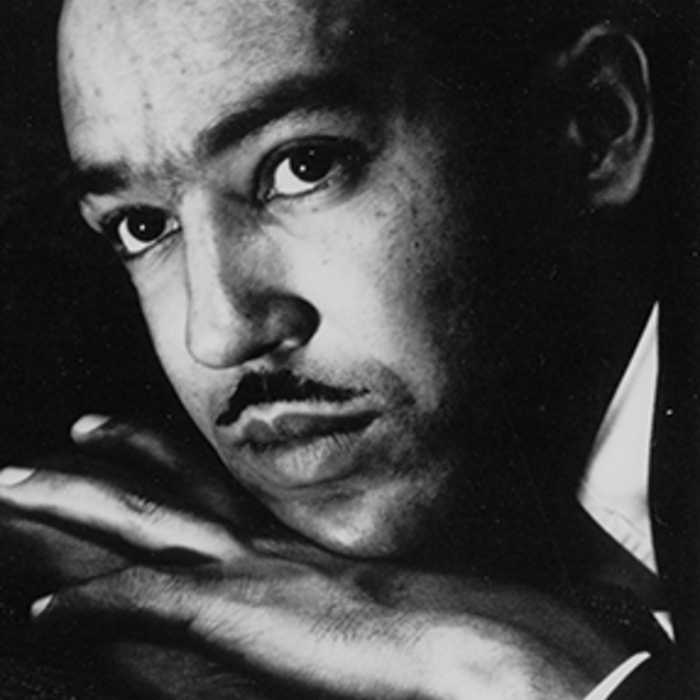

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, New Jersey, on October 7, 1934. His father, Colt Jones, was a postal supervisor; Anna Lois Jones, his mother, was a social worker. He attended Rutgers University for two years, then transferred to Howard University, where in 1954 he earned his BA in English. He served in the Air Force from 1954 until 1957, then moved to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. There he joined a loose circle of Greenwich Village artists, musicians, and writers. The following year he married Hettie Cohen and began coediting the avant-garde literary magazine Yugen with her. That year, he also founded Totem Press, which first published works by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and others.

Baraka’s published his first volume of poetry, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, in 1961. From 1961 to 1963 he was coeditor, with Diane Di Prima, of The Floating Bear, a literary newsletter. His increasing mistrust of white society was reflected in two plays: The Slave and The Toilet, both written in 1962. Blues People: Negro Music in White America, which he wrote, and The Moderns: An Anthology of New Writing in America, which he edited and introduced, were both published in 1963. His reputation as a playwright was established with the production of Dutchman at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York on March 24, 1964. The controversial play subsequently won an Obie Award (for “best off-Broadway play”) and was made into a film.

In 1965, following the assassination of Malcolm X, Baraka repudiated his former life and ended his marriage. He moved to Harlem, where he founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. The company, which produced plays that were intended for a black audience, dissolved in a few months. He moved back to Newark and, in 1967, he married poet Sylvia Robinson (now known as Amina Baraka). That year, he also founded the Spirit House Players, which produced, among other works, two of Baraka’s plays against police brutality: Police and Arm Yrself or Harm Yrself.

In 1968, Baraka coedited Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing with Larry Neal and his play Home on the Range was performed as a benefit for the Black Panther Party. That same year he became a Muslim, changing his name to Imamu Amiri Baraka. He assumed leadership of his own Black Muslim organization, Kawaida. From 1968 to 1975, Baraka was chairman of the Committee for Unified Newark, a Black united front organization. In 1969, his Great Goodness of Life became part of the successful “Black Quartet” off-Broadway, and his play, Slave Ship, was widely reviewed. Baraka was a founder and chairman of the Congress of African People, a national Pan-Africanist organization with chapters in fifteen cities, and he was one of the chief organizers of the National Black Political Convention, which convened in Gary, Indiana in 1972 to organize a more unified political stance for African Americans.

In 1974, Baraka adopted a Marxist Leninist philosophy and dropped the spiritual title “Imamu.” In 1983, he and Amina Baraka edited Confirmation: An Anthology of African American Women, which won an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, and, in 1987, they published The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues. The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka was published in 1984.

Baraka’s numerous literary prizes and honors include fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the PEN/Faulkner Award, the Rockefeller Foundation Award for Drama, the Langston Hughes Award from the City College of New York, and a lifetime achievement award from the Before Columbus Foundation.

Baraka taught poetry at the New School for Social Research in New York, literature at the University of Buffalo, and drama at Columbia University. He also taught at San Francisco State University, Yale University, and George Washington University. For two decades, Baraka was a professor of Africana Studies at the State University of New York in Stony Brook. He was codirector, with his wife, of Kimako’s Blues People, a community arts space.

Baraka died in Newark on January 9, 2014.