For You, a Handful of the Greatest Gift

Small-eyed, plump, and with black

leathery hands, Attaskwa, is composed

and debonair

as it perches on trampled cat tail reeds

beside a quivering, cloud-reflecting pond.

“Filled

with cosmogony, he’s exceedingly

unselfish,” instructs the branch-shaping

sculptor.

“Wabami, Look at him, kekenetama,

he knows. And he’s elated to oversee

what

the daylight brings everyday.”

We focus the camera’s telephoto lens

and see

details of his coat glittering with drops

of luminescent water.

“To our Grandfather, Kemettoemenana,”

narrates the sculpture, “he magnanimously

agreed after

the Last Conflict of the Gods to retrieve

a handful of soil from the deep, singular

ocean that

became land beneath our feet. He

set forth unequivocally a doctrine.

Listen

very closely, my grandchildren,

nottisemetike, for you may not hear

these words

again.” Lifting its black nose

to the sky, Attaskwa ambles

to the pond’s

edge and stops as if to pose

before the picture is snapped.

Behind us,

the sculptor crafts a small

dome-shaped skeletal lodge

and

embeds it to the ground.

We wholly agree that each day

there are overt and minute changes.

Even if we

don’t see or if we’re not there, it happens.

Without Muskrat, our Creation—you

and me,

would be zero. From the alluvial soil

delivered from oceanic depths, we

were made

thereafter. His courage is brazen like

that of a Wetase, Veteran, because he

dove

unflinchingly to retrieve Earth.

Oblivious of our presence, Attaskwa

slides into the pond and swims

to the middle,

creating a cape-like effect of waves

behind him that dissipates

the blue sky

and its clouds. Indicative of his

sacrifice, we learn Attaskwa floated

lifeless

to the surface. In gratitude Earth-maker

resurrected him. So when personal

contributions

are contemplated, ask yourself,

my daughter and son, what did I

sacrifice?

Think specifically of what he did.

Use him, my children, netabenoemetike,

as an example

of what must be done to rectify

society’s misdirection. Only then

will our,

language, religion, culture, and history

thrive in the Muskrat’s benevolent

shadow.

As he approaches the mound

of his home, Attaskwa looks back

at us briefly.

And before his cape of waves reaches

the shoreline, he dives into the dark

green pond.

Before we pack up the equipment,

the sculptor hands us sacred

tobacco

to sprinkle delicately over

the water animal’s architectural

tranquility.

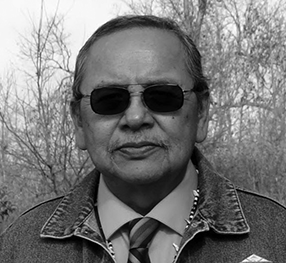

From Manifestation Wolverine. Copyright © 2015 by Ray A. Young Bear. Used with the permission of the author.