On Translation

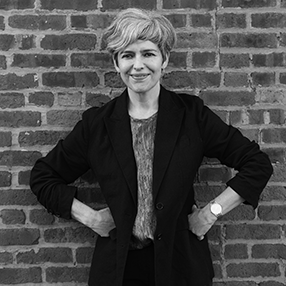

Not to search for meaning, but to reedify a gesture, an intent. As a translator, one grows attached to originals. Seldom are choices so purposeful. At midday, the translator meets with the poet at a café at the intersection where for decades whores and cross-dressers have lined up at night for passers-by to peruse. Not a monologue, but an implied conversation. The translator's response is delayed. The translator asks, the poet answers unrestrictedly. Someone watches the hand movements that punctuate the flow of an incomprehensible dialogue. They're speaking about the poet's disillusionment with Freud. One after another, vivid descriptions of the poet's dreams begin to pour out of his mouth. There's no signal of irony in his voice. Nor a hint of astonishment, nor a suggestion of hidden meanings, rather a belief in the detritus theory. "Se me aparece un gato fosforescente. Lo sostengo en mis brazos sabiendo que no volveré a ser el mismo." "Estoy en una fiesta. De pronto veo que el diablo está sentado frente a mí. Viste de negro, lleva una barba puntiaguda y un tridente en la mano izquierda. Es tan amable que nadie se da cuenta de que no es un invitado como los otros." "Anuncian en el radio que Octavio Paz leerá su poema más reciente: 'Vaca . . . vaca . . . vaca . . . vaca . . . vaca . . . vaca . . . vaca . . .'" "Entro a un laboratorio y percibo aromas inusitados. Aún los recuerdo." The translator knows that nothing the poet has ever said or written reveals as much about him as the expression on his face when he was asked to pose for a picture. He greets posterity with a devilish grin. To the translator's delight, he's forced to repeat the gesture at least three or four times. The camera has no film.

Credit

Reprinted from American Poet, Fall 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Mónica de la Torre. Reprinted by permission of the poet. All rights reserved.

Date Published

01/01/2002