Tag at Pullman National Monument

The market is made of fire so nothing

Stands, or stands—even in the ideal

City of Pullman, I hear “nigga run,”

One child shouting to another in ruins,

Of ruin and so call out in paradise

To the live bloody skeleton hung softly

As summer in each other to escape

This year’s killing season, the pilgrimage

To flame and morgue and news and dust, local

Honey sold nationally, the market

Always-already wet with this black fame.

In an alley beyond their beware and boy-

Barking, a painting of a Maasai warrior

Lifting himself out of the frame with a leap,

His spear, nothing like fire but a fire

The leaping, the leaving of the coffin-

Pull of earth, his red garment about him

In clasped silence for which we understand

That we will not understand and so stare

At something else trying to escape

Paradise. Beauty has always belonged

To whomever could afford it. None of us

Can afford what we pay for beauty, but

We labor, we labor, our white rag wet

With formaldehyde, our knees deep in shag

Carpet pressing a stain as commanded

By a mastering manual kept in a slim slash

Pocket, our white charges sleeping their way

Across cud-chewing to Chicago

Dreaming of a man they watched burn this tree-side

Of heaven. “Run nigga,” the boys yell

As if hocking oranges in a burning market,

As if what they flee is not each other.

Copyright © 2016 by Roger Reeves. This poem was commissioned by the Academy of American Poets and funded by a National Endowment for the Arts Imagine Your Parks grant.

"Utopias don’t last long if they last at all. The poem begins with a building that can do nothing but burn throughout the twentieth century in a utopic community built by the railroad magnate, George Pullman, for his workers, a community that very few people of color lived in until recently. While visiting the National Park of Pullman, my ear was pulled toward the boys playing tag, weaving in and out of yards and parked cars, yelling ‘run, nigga.’ The boys yelling ‘run, nigga’ seemed like both a warning and celebration, particularly in a city like Chicago where this type of entreaty could be both threat and jubilee. Though the boys were playing in the alleyways and streets, shouting back and forth to each other, because of the sirens nearby, their play was always circumscribed or, at the very least, in conversation with the violence that consumes the national news and the reigning narrative about Chicago. I couldn’t help but write into and about these juxtapositions and contradictions."

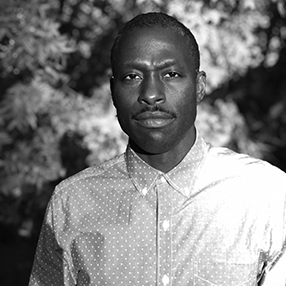

—Roger Reeves