The Sluggard

’Tis the voice of the Sluggard: I heard him complain,

“You have wak’d me too soon, I must slumber again;”

As the door on its hinges, so he on his bed,

Turns his sides, and his shoulders, and his heavy head.

“A little more sleep, a little more slumber,”

Thus he wastes half his days and his hours without number;

And when he gets up he sits folding his hands,

Or walks about saunt’ring, or trifling he stands.

I pass’d by his garden, and saw the wild brier,

The thorn and the thistle, grow broader and higher.

The clothes that hang on him are turning to rags:

And his money still wastes, till he starves or he begs.

I made him a visit still hoping to find

He had took better care for improving his mind:

He told me his dreams, talk’d of eating and drinking;

But he scarce reads his Bible, and never loves thinking.

Said I then to my heart, “Here’s lesson for me;

That man’s but a picture of what I might be:

But thanks to my friends for their care in my breeding,

Who taught me betimes to love working and reading.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on July 15, 2023, by the Academy of American Poets.

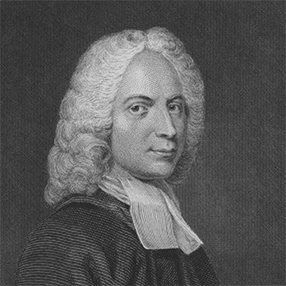

“In the history of Christian hymnody in English, you had, for centuries, David’s Psalms in translation, and then, strolling the lovely grounds of a manor in Stoke Newington, you had Isaac Watts. Gifted with an easy, elegant originality of phrase and rhyme, Watts was also famous for songs exhorting children to be good and not to ‘tear each other’s eyes.’ Idleness, however, was the worst of possible evils. It is here that we stumble into a bed of thorns. Oppression is often internalized, and literature by disabled writers is rife with ableism, not just toward people with other disabilities, those ‘worse off’ than us, but also toward someone else with our own disability. Self-flagellation, too, lurks close by. Watts’s portrayal of and attitude toward a ‘sluggard’ is problematic but not without its lessons for us about the power of care. After his second illness in 1712, Watts never regained full strength. Friends took him in, and he eventually found an open home with Sir Thomas and Lady Mary Abney, where, for thirty-six years he enjoyed, to quote the hymn writer Thomas Gibbons, ‘the privilege of a country recess, the fragrant bower, the spreading lawn, the flowery garden, and other advantages, to soothe his mind and aid his restoration to health [. . .].’ Gibbons went on to echo the speaker of ‘The Sluggard’: ‘Had it not been for this most happy event, he might [. . .] have feebly, it may be painfully, dragged on through many more years of languor and inability for public service, and even for profitable study, or perhaps might have sunk into his grave under the overwhelming load of infirmities [. . .].’ Instead, this exceptional support produced an astonishing body of work—hymns, poems, theological treatises, essays, and a popular textbook on logic. Samuel Johnson observed that, in Watts’s case, ‘notions of patronage and dependence were overpowered by the perception of reciprocal benefits,’ a dynamic that would later inform disability justice around care work.”

—John Lee Clark