The Shadow on the Stone

I went by the Druid stone

That stands in the garden white and lone,

And I stopped and looked at the shifting shadows

That at some moments there are thrown

From the tree hard by with a rhythmic swing,

And they shaped in my imagining

To the shade that a well-known head and shoulders

Threw there when she was gardening.

I thought her behind my back,

Yea, her I long had learned to lack,

And I said: “I am sure you are standing behind me,

Though how do you get into this old track?”

And there was no sound but the fall of a leaf

As a sad response; and to keep down grief

I would not turn my head to discover

That there was nothing in my belief.

Yet I wanted to look and see

That nobody stood at the back of me;

But I thought once more: “Nay, I’ll not unvision

A shape which, somehow, there may be.”

So I went on softly from the glade,

And left her behind me throwing her shade,

As she were indeed an apparition—

My head unturned lest my dream should fade.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on October 16, 2022, by the Academy of American Poets.

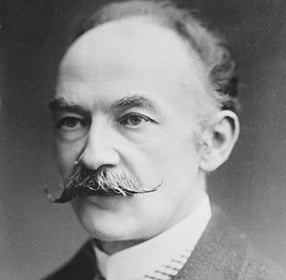

“The Shadow on the Stone” was first published in Moments of Vision and Miscellaneous Verses (Macmillan and Co., 1917), though it was written between the years 1913 and 1916 according to a note included with the poem. Like many of Hardy’s poems from this period, “The Shadow on the Stone” is often considered to be a response to the death of his first wife, Emma Gifford, who died suddenly on November 27, 1912. Still, many critics have ventured beyond a strictly autobiographical reading of the poem, such as Irish scholar Thomas Duddy, who, remarking on the poem’s evocation of the Orpheus-Eurydice myth in “The Shadow on the Stone: Memory and ‘Vision’ in the Poetry of Thomas Hardy,” published in The Hardy Society Journal vol. 8, no. 1 (Spring 2012), writes that “[l]ike Orpheus, who was warned to resist the temptation to look back at Eurydice, the narrator confesses to the strength of his temptation to turn around, but he resolves, unlike Orpheus, not to do anything that would deprive him of his sense of a presence behind him.” Later in the same essay, Duddy declares, “To wonder, in the aftermath of reading such a poem, if there really could have been an apparition in the garden, or if the narrator’s experience was just an illusion or trick of the mind, is to adopt an uncomprehending, reductive, anti-literary attitude to both the kind of human experience that is preserved in the poem, and the traditions of story, myth and belief that human communities have developed in the course of responding to such experiences. Just as the shadow [. . .] is as real to eye and mind as the stone on which it falls, so loved ones remembered or ‘sensed’ in their grievous absence, are as real to memory and imagination—and to the emotional life—as the apparitions of folklore and myth.”