To See as Far as the Grandfather World

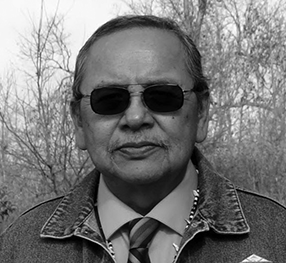

The photograph. On this particular March day

in 1961, Theodore Facepaint, who was nine

years old, agreed to do a parody. With hand

balanced on hip and the left leg slightly

in front of the right, my newly found friend

positioned himself on Sand Hill before turning

to face the hazy afternoon sun. This was a pose

we had become familiar with:

the caricature

of a proud American Indian, looking out

toward the vast prairie expanse, with one hand

shielding the bronze eyes. When I projected

the image of the color 35 mm slide onto

the wall last week I remembered the sense

of mirth in which it was taken. Yet somewhere

slightly north of where we were clowning around,

Grandmother was uprooting medicinal roots

from the sandy soil

and placing them inside her flower-patterned

apron pockets to thaw out.

Twenty-nine years later, if I look long enough,

existential symbols are almost detectable.

The direction of the fiery sun in descent, for example,

is considered the Black Eagle Child Hereafter.

Could I be seeing too much? Past the west

and into the Grandfather World? Twice

I’ve caught myself asking:

Was Ted’s pose portentous? When I look

closely at the background of the Indian Dam

below—the horizontal line of water that runs

through the trees and behind Ted—I also know

that Liquid Lake with its boxcar-hopping

light is nearby.

For Ted and his Well-Off Man Church,

the comets landed on the crescent-shaped

beach and lined themselves up for a ritualistic

presentation. For Jane Ribbon, a mute healer,

a seal haunted this area. But further upriver

is where the ancient deer hunter was offered

immortality by three goddesses. While

the latter story of our geographic genesis

is fragmented, obscuring and revealing

itself as a verisimilitude, it is important.

Ted and I often debated what we would

have done had we been whisked through

a mystical doorway to a subterranean enclave.

Ted, unlike the ancient hunter who turned

down paradise, would have accepted—

and the tribe never would have flexed

its newborn spotted wings. In the hunter’s

denial we were thus assigned as Keepers

of Importance. But the question being asked

today is, Have we kept anything?

Our history, like the earth with its

abundant medicines, Grandmother used

to say, is unfused with ethereality. Yet in

the same breath she’d openly exclaim

that with modernity comes a cultural toll.

In me, in Ted, and everyone.

Stories then, like people, are subject to change.

More so under adverse conditions. They

are also indicators of our faithfulness. Since

the goddesses’ doorway was sealed shut by

our own transgressions,

Grandmother espoused that unbounded

youth would render tribal language

and religion inept, that each lavish

novelty brought into our homes would

make us weaker until there was nothing.

No lexicon. No tenets.

Zero divine intervention. She was also

attuned to the fact that for generations

our grandparents had wept unexpectedly

for those of us caught in the blinding

stars of the future.

Mythology, in any tribal-oriented society,

is a crucial element. Without it, all else

is jeopardized with becoming untrue. While

the acreages beneath Ted’s feet and mine

offered relative comfort back then,

we are probably more accountable now

to ourselves—and others.

Prophecy decrees it. Most fabled among

the warnings is the one that forecasts

the advent of our land-keeping failures.

Many felt this began last summer when

a whirlwind abruptly ended a tribal

celebration. From the north in the shape

of an angry seagull it swept up dust.

corn leaves, and assorted debris,

as it headed toward the audacious

“income-generating architecture,”

the gambling hall. At the last second

the whirlwind changed direction, going

toward the tribal recreation complex.

Imperiled, the people within the circus tent-

like structure could only watch as the panels

flapped crazily. A week later, my family said

the destruction was attributable to the gambling

hall, which was the actual point of weakness

of the tribe itself.

Which is to say the hill where a bronze-eyed

Ted once stood is under threat of impermanence.

By allowing people who were not created

by the Holy Grandfather to lead us we may

cease to own what Ted saw on the long-ago day.

From Rolling Head Valley to Runner’s Bluff

and over the two rivers

our hold is gradually being unfastened by

false leaders. They have forgotten that their

own grandparents arrived here under a Sacred

Chieftain. This geography is theirs nonetheless.

and it shall be as long as the first gifts given

are intact. In spite of everything that we are

not, this crown of hills resembles lone islands

amid an ocean of corn, soybean fields,

and low-lying fog. Invisibly clustered on

the Black Eagle Child Settlement’s slopes

are the remaining Earthlodge clans.

The western edge of this

woodland terrain overlooks the southern

lowlands of the Iowa and Swanroot Rivers,

while the eastern edge splits widely into several

valleys, where the Settlement’s main road winds

through. It is on this road where Ted and I walked.

It is on this road where Ted met a pack

of predators.

Along the color slide’s paper edge the year

1961 is imprinted. Ted and I were fourth

graders at Weeping Willow Elementary.

Nine years later, in 1970, a passenger train

took us to Southern California for college.

It proved to be a lonely place where winter

appeared high atop

the San Gabriel Mountains on clear days.

Spanish-influenced building styles, upper-middle-

class proclivities, and the arid climate had a subtle

asphyxiating effect. Instead of chopping firewood

for father’s nonexistent blizzard,

I began my evenings in Frary Dining Hall

where Orozco’s giant mural with erased privates

called Prometheus loomed above. My supper

would consist of tamales and cold shrimp salad

instead of boiled squirrel with flour dumplings.

Through mountain forest fires the Santa Ana

winds showered the campus with sparks and ashes.

In a wide valley where a smoke- and smog-darkened

night came early, the family album possessed its

own shimmery light. Pages were turned. A visual

record of family and childhood friends. Time.

Ted and I transforming,

separating. During the first Christmas break

in which we headed back to the Black Eagle

Child Settlement, Ted froze me in celluloid:

against a backdrop of snow-laden pine trees

a former self wears a windswept topcoat,

Levi bell-bottoms, cowboy boots, and tinted

glasses. Ted and I, like statues, are held

captive in photographic moments.

As the earth spins, however,

the concrete mold disintegrates,

exposing the vulnerable wire

foundation of who we are not.

From Remnants of the First Earth (Grove Press, 1996). Copyright © 1996 by Ray A. Young Bear. Used with the permission of the author.