To My Oldest Friend, Whose Silence Is Like a Death

In today’s paper, a story about our high school drama teacher evicted from his Carnegie Hall rooftop apartment made me ache to call you—the only person I know who’d still remember his talent, his good looks, his self- absorption. We’d laugh (at what haven’t we laughed?), then not laugh, wondering what became of him. But I can’t call, because I don’t know what became of you. —After sixty years, with no explanation, you’re suddenly not there. Gone. Phone disconnected. I was afraid you might be dead. But you’re not dead. You’ve left, your landlord says. He has your new unlisted number but insists on “respecting your privacy.” I located your oldest son, who refuses to tell me anything except that you’re alive and not ill. Your ex-wife ignores my letters. What’s happened? Are you in trouble? Something you’ve done? Something I’ve done? We used to tell each other everything: our automatic reference points to childhood pranks, secret codes, and sexual experiments. How many decades since we started singing each other “Happy Birthday” every birthday? (Your last uninhibited rendition is still on my voice mail.) How often have we exchanged our mutual gratitude—the easy unthinking kindnesses of long friendship. This mysterious silence isn’t kind. It keeps me up at night, bewildered, at some “stage “of grief. Would your actual death be easier to bear? I crave your laugh, your quirky takes, your latest comedy of errors. “When one’s friends hate each other,” Pound wrote near the end of his life, “how can there be peace in the world?” We loved each other. Why why why am I dead to you? Our birthdays are looming. The older I get, the less and less I understand this world, and the people in it.

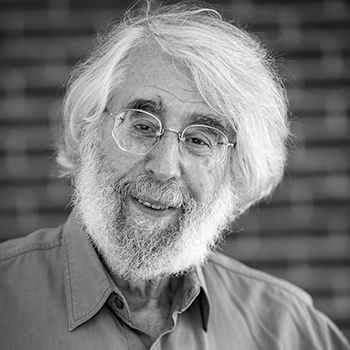

Copyright © 2014 by Lloyd Schwartz. Used with permission of the author. This poem appeared in Poem-A-Day on February 27, 2014. Browse the Poem-A-Day archive.

“This poem was written out of great sadness, about the sudden and inexplicable loss, though not the literal death, of a friend—my oldest friend, a friend since childhood. It’s a common trope to address a poem to someone we know won’t read it—someone who has actually died, a former lover, even a lost object. The act of putting our losses into words and letting the world eavesdrop seems some sort of consolation, or at least an acknowledgement that we all suffer such losses. Here, the most painful element is the very mystery of this disconnection, which for me gives Pound’s poignant late-in-life lament such particular resonance.”

—Lloyd Schwartz