My Life Is a Memory

translated from the Spanish by William George Williams

When I met her I loved myself.

It was she who had my best singing,

she who set flame to my obscure youth,

she who raised my eyes toward heaven.

Her love moistened me, it was an essence.

I folded my heart like a handkerchief

and after I turned the key on my existence.

And thus it perfumes my soul

with a distant and subtle poetry.

Mi vida es un recuerdo

Cuando la conocí me amé á mí mismo.

Fué la que tuvo mi mejor lirismo,

la que encendió mi obscura adolescencia,

la que mis ojos levantó hacia el cielo.

Me humedeció su amor, que era una esencia,

doblé mi corazón como un pañuelo

y después le eché llave á mi existencia.

Y por eso perfuma el alma mía

con lejana y diluida poesía.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on October 9, 2022, by the Academy of American Poets.

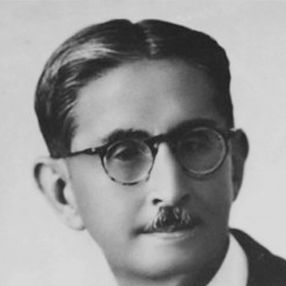

“My Life Is a Memory” first appeared as “Mi vida es un recuerdo” in Los atormentados (R. Gutiérrez y cía., 1914). Later an English translation of the poem by William George Williams was published in Others: A Magazine of the New Verse vol. 3, no. 2, (August 1916), a themed issue of the magazine dedicated to Spanish American poetry. Discussing the issue’s ambitions to “situate South and Central American poets within its modernist project,” scholar Gabriele Hayden writes, in “Situating Latin America within U.S. Modernism: Others’s Spanish American Avant-Garde,” published in Revues modernistes, revues engagées (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2011), that “Rafael Arévalo Martínez, the writer with the most poems included in Others, sometimes approaches a plain style. His early poetry is characterized in general by a fin de siècle sensibility, and critics generally concur that is only later in his career, in the 1930s, 1940s, and 50s, that Martínez turned definitively towards a declarative style that might be characterized as more recognizably ‘modernist’ in the Anglo-American sense of the term. Yet the selection of Martínez’s poems in Others includes works [. . .] that anticipate Martinez’s later, sparer poetry.” That the “still-nascent postmodernismo” style of Latin American poets such as Martínez who were included the Spanish American issue of Others conformed with the modernist sensibilities of its American editors is clarified by the fact that “Modernismo, despite its name, was a movement that preceded the peak of Anglo-American modernism by close to twenty years [. . .].”