That Morning after the Assassination of Malcolm X

“Terror on every side! Denounce him! Let us denounce him!”

All my friends are waiting for me to slip. They say,

“Perhaps he will be deceived; then we will prevail

over him and take our revenge on him.” Jeremiah 20:10

“Get back on the train,” he said. “Then go back

downtown to 59th, and take the Number One.”

He was in his mid-fifties, I think, the man behind

the booth. Brown, soft spoken, eyes down.

“Then take the train back uptown to 116th

and get off at Columbia University.” He told

me this I have come to see to keep me

from getting off the train there in Harlem

on that dead and silent morning. No, I told

myself. After all, I was already up at 116th.

Easier to just walk up the subway steps, cut through

the park at Morningside and on to the campus.

This was February 22nd, 1965,

a bright crisp Monday morning. I’d come up

on the subway from Hunter to get a copy

of How to Read French which the adjunct at Hunter

had assigned us. One more way of talking

I’d have to learn to pass my PhD exam come fall.

One more piece of that jagged jigsaw puzzle

I’d have to fit together if I was ever going to earn

my degree in English and Comp Lit from the dons

at the City University of New York.

Understand: I was a week shy of my twenty-fifth,

married now eighteen months, and living

in a two-family apartment on Booth Memorial

out in far-flung Flushing, our firstborn

already well on his way. The fact that a Black

man named Malcolm X had just been killed

with a blast from a hidden sawed-off shotgun

the afternoon before at the Audubon Ballroom

north of here in Harlem had registered, I think,

but barely. But what had any of this to do with me?

This was New York City, you have to understand,

and this was the Sixties. And what did I know

anyway about this Malcolm with that X in place of

some white slave master’s name? And wasn’t this

the guy who, when JFK was shot down in Dallas

fifteen months before, had said how the chickens

had finally come home to roost? The same man

who’d called Cassius Clay (now, thanks to him

Muhammed Ali) his close friend until they too

had parted ways (to Ali’s too-late regret)? The man

who once took on William Buckley in that debate about

white privilege, and won? Only after I got my prized

degree and moved on to teach up in Amherst did I

begin to put the pieces of the puzzle back together

when I came at last to teach Malcolm’s autobiography,

and learned what courage the man had to have to face

down the rank corruption in the leader he’d followed

for a dozen years, the prophet Elijah Muhammed,

and turned instead to Mecca for the strength

he saw the faithful offered so he could carry on,

in spite of being targeted by the FBI

and New York’s Finest, the dark side of human

nature being what it is. Add to all of this his beloved

Betty there on that stage with him, mother of their

four daughters, with two more on the way, whom

he would never live to see. Add too the gunshot

wounds to his chest, left shoulder, arms and legs,

the blood gurgling from his mouth as he lay dying.

And hadn’t the leader of the Nation, miffed at

Malcolm’s leaving, made it known how the man

was now a traitor and so must die. And if he himself

washed his hands of the job, not so his followers.

And now Malcolm X Shabazz was dead.

Though not his message. No, not what he had

had to learn the hard way, about the cost of learning

to love your brother, black, brown or even white.

That ice-cold morning, as I walked the ghostlike streets

of Harlem toward the looming Heights, two young

Black men in dark suits stood there on the sidewalk

talking, surprised to see a white man like myself

with a briefcase in his hand walking there, even as

it dawned on me that I might well be in the wrong

place at the wrong time. And here’s the thing: like two

angels, they stared, winked, parted, and let me pass.

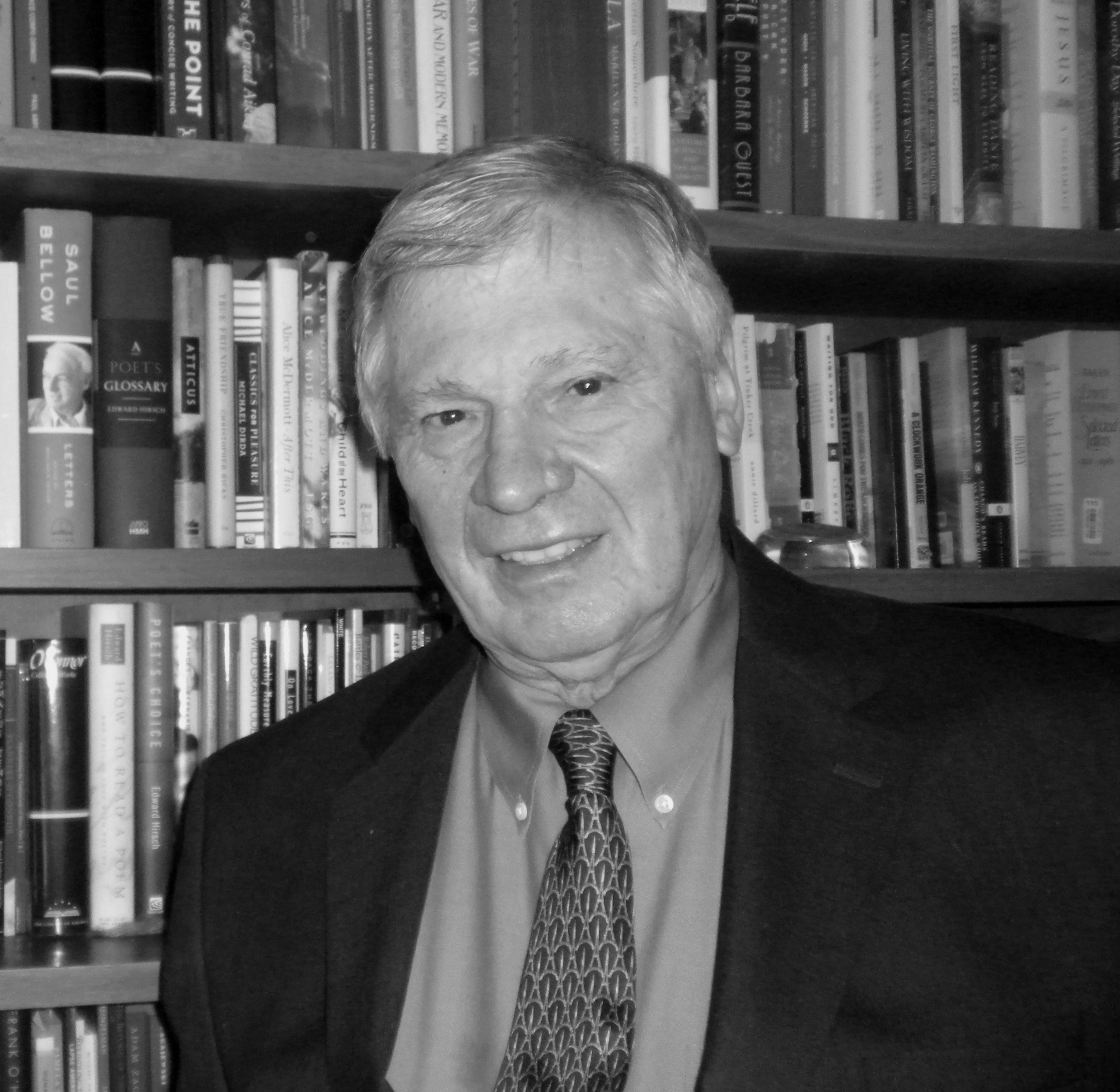

From All That Will Be New (Slant Books, 2022) by Paul Mariani. Copyright © 2022 by Paul Mariani. Used with the permission of the author.