January

Cold is the winter day, misty and dark:

The sunless sky with faded gleams is rent:

And patches of thin snow outlying, mark

The landscape with a drear disfigurement.

The trees their mournful branches lift aloft:

The oak with knotty twigs is full of trust,

With bud-thronged bough the cherry in the croft;

The chestnut holds her gluey knops upthrust.

No birds sing, but the starling chaps his bill

And chatters mockingly; the newborn lambs

Within their strawbuilt fold beneath the hill

Answer with plaintive cry their bleating dams.

Their voices melt in welcome dreams of spring,

Green grass and leafy trees and sunny skies:

My fancy decks the woods, the thrushes sing,

Meadows are gay, bees hum and scents arise.

And God the Maker doth my heart grow bold

To praise wintry works not understood,

Who all the worlds and ages doth behold,

Evil and good as one, and all as good.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on January 4, 2025, by the Academy of American Poets.

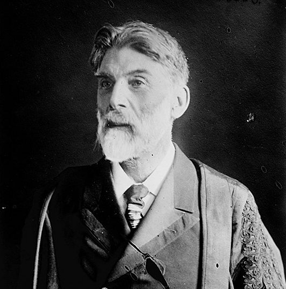

“January” appears in the Poetical Works of Robert Bridges (Oxford University Press, 1913). In the article “Robert Bridges and the Free Verse Rebellion,” American poet and critic Donald E. Stanford noted, “It is not generally recognized that Robert Bridges was (in his own way) involved in the free verse rebellion of the 1910s and 1920s. Although he was seventy years old in 1914 when one of the most important volumes of the new movement, Des Imagistes, appeared, he was still keenly aware of what was going on among the younger poets of his time, and like them, he had become dissatisfied with conventional rhythms based on the iambic foot. In this year he wrote ‘My own opinion is that, especially in the present condition of English verse, all methodical experiments are of value, and that a competent experiment is of value even though it may not please.’ […] As the Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot revolution began to dominate the literary scene in the later twenties and down to the present time, Bridges’s milder and more refined experiments have been overlooked by most critics. Yet a history of the twentieth century experimental movement in Anglo-American poetry should not completely disregard Bridges’s later work.”