Ipswich

In Ipswich nights are cool and fair,

And the voice that comes from the yonder sea

Sings to the quaint old mansions there

Of “the time, the time that used to be”;

And the quaint old mansions rock and groan,

And they seem to say in an undertone,

With half a sight and with half a moan:

“It was, but it never again will be.”

In Ipswich witches weave at night

Their magic spells with impish glee;

They shriek and laugh in their demon flight

From the old Main House to the frightened sea.

And ghosts of eld come out to weep

Over the town that is fast asleep;

And they sob and they wail, as on they creep:

“It was, but it never again will be.”

In Ipswich riseth Heart-Break Hill

Over against the calling sea;

And through the nights so deep and chill

Watcheth a maiden constantly,—

Watcheth alone, nor seems to hear

Over the roar of the waves anear

The pitiful cry of a far-off year:

“It was, but it never again will be.”

In Ipswich once a witch I knew,—

An artless Saxon witch was she;

By that flaxen hair and those eyes of blue,

Sweet was the spell she cast on me.

Alas! but the years have wrought me ill,

And the heart that is old and battered and chill

Seeketh again on Heart-Break Hill

What was, but never again can be.

Dear Anna, I would not conjure down

The ghost that cometh to solace me;

I love to think of old Ipswich town,

Where somewhat better than friends were we;

For with every thought of the dear old place

Cometh again the tender grace

Of a Saxon witch’s pretty face,

As it was, and is, and ever shall be.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on October 27, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

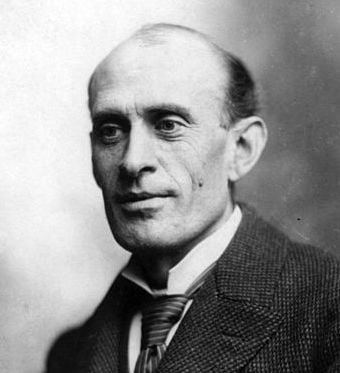

“Ipswich” is found in The Poems of Eugene Field (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906). In Modern American Poetry (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921), edited by Louis Untermeyer, Untermeyer noted of Field: “He wrote so often with his tongue in his cheek that it is difficult to say where true sentiment stops and an exaggerated sentimentality begins. ‘Field,’ says Fred Lewis Pattee, in his detailed study of American Literature Since 1870, ‘more than any other writer of the period, illustrates the way the old type of literary scholar was to be modified and changed by the newspaper. Every scrap of Field’s voluminous product was written for immediate newspaper consumption. He patronized not all the literary magazines, he wrote his books not at all with book intent––he made them up from newspaper fragments.… He was a pioneer in a peculiar province: he stands for the journalization of literature, a process that, if carried to its logical extreme, will make of the man of letters a mere newspaper reporter.’”