Inheritance of Waterfalls and Sharks

for my son Klemnte

In 1898, with the infantry from Illinois,

the boy who would become the poet Sandburg

rowed his captain's Saint Bernard ashore

at Guánica, and watched as the captain

lobbed cubes of steak at the canine snout.

The troops speared mangos with bayonets

like many suns thudding with shredded yellow flesh

to earth. General Miles, who chained Geronimo

for the photograph in sepia of the last renegade,

promised Puerto Rico the blessings of enlightened civilization.

Private Sandburg marched, peeking at a book

nested in his palm for the words of Shakespeare.

Dazed in blue wool and sunstroke, they stumbled up the mountain

to Utuado, learned the war was over, and stumbled away.

Sandburg never met great-great-grand uncle Don Luis,

who wore a linen suit that would not wrinkle,

read with baritone clarity scenes from Hamlet

house to house for meals of rice and beans,

the Danish prince and his soliloquy—ser o no ser—

saluted by rum, the ghost of Hamlet's father wandering

through the ceremonial ballcourts of the Taíno.

In Caguas or Cayey Don Luis

was the reader at the cigar factory,

newspapers in the morning,

Cervantes or Marx in the afternoon,

rocking with the whirl of unseen sword

when Quijote roared his challenge to giants,

weaving the tendrils of his beard when he spoke

of labor and capital, as the tabaqueros

rolled leaves of tobacco to smolder in distant mouths.

Maybe he was the man of the same name

who published a sonnet in the magazine of browning leaves

from the year of the Great War and the cigar strike.

He disappeared; there were rumors of Brazil,

inciting canecutters or marrying the patrón's daughter,

maybe both, but always the reader, whipping Quijote's sword overhead.

Another century, and still the warships scavenge

Puerto Rico's beaches with wet snouts. For practice,

Navy guns hail shells coated with uranium over Vieques

like a boy spinning his first curveball;

to the fisherman on the shore, the lung is a net

and the tumor is a creature with his own face, gasping.

This family has no will, no house, no farm, no island.

But today the great-great-great-grand nephew of Don Luis,

not yet ten, named for a jailed poet and fathered by another poet,

in a church of the Puritan colony called Massachusetts,

wobbles on a crate and grabs the podium

to read his poem about El Yunque waterfalls

and Achill basking sharks, and shouts:

I love this.

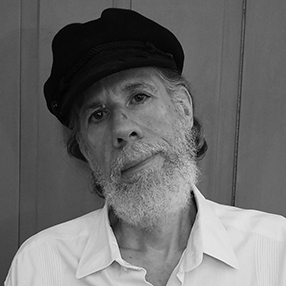

"Inheritance of Waterfalls and Sharks," from Alabancza by Martín Espada. Copyright © 2003 by Martín Espada. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.