How I Pray in the Plague

I was rehearsing the ecstasies of starvation

for what I had to do. And have not charity,

I found my pity, desperately researching

the origins of history, from reed-built communes

by sacred lakes, turning with the first sprocketed

water-driven wheels.

—Derek Walcott

In these silences, the bubbles of hurt are indistinguishable from the terror

that lurks in the body—the phrase, “ecstasies of starvation” will have a music

that lures us to peace, but how do I stay with a tender heart of peace and calm

when I slow in my walk in the face of an old saying that has hidden its conundrum

of theology from me—perhaps not hidden, perhaps what I mean is before

I found my pity, my charity, my love, I could slip over the conundrums,

lead us not into temptation—that imperative that has no sensible answer,

for is this the way of a father, and what kind of father must be asked not to tempt me?

And what of the mercy of temptation, and what of the lessons of temptation,

and what of the diabolical cruelty of testing—you see why I slip over this

with the muteness of the faith that must grow in increments of meaning?

In these silences, the bubbles of anxiety, the hurt I cannot distinguish from terror

is my daily state, and you teach me to pray in this way, and in this way, you teach me

the path of being led into terror. I will say this and let it linger, and what I mean

is that this is the way of poetry for me, for much of what I offer, I am sure of nothing,

the knowing or the outworking, but the trust of its history of resolution—so that I will say,

this is the origin of history, and by this, I mean this small conundrum: “Lead us not,

lead me not, lead them not, lead them not,” And what is this were it not the way

we know the heavy hand of God—that to pray, “Lead them not into temptation”,

is a kind of mercy, and to say, “Lead us not”, is the penitence of a sinning nation

desperate for the lifting of the curses of contagion and plague. The subtext is the finger

pointed at the culprit. So that what kind of father do I tell this to? Might I have said,

“Neville, please, lead me not into temptation”, what would it mean to tell my old man

not to lead me into temptation? Must that not be the same as a reprimand to my father,

a judgment on his propensity to fail me?

Do you want answers? You have come to the wrong

place. I am selfish with answers. I am hoarding all answers. Go, instead, to the prophets

and the preachers, the soothsayers and priests, go to the pundits and the dream readers,

to the pontiffs and kings, to the presidents and mayors, to the brokers in answers. But me,

I hoard the secrets of my calming beauty, and I walk this road, not as a maker of questions—

this would be a crude wickedness—but with the fabric of our uncertainty, a net stretched

across the afternoon sky, this is beauty and in this I will trade until all music ends, and the air

grows crisp as airless grace. They say that if you find honey in the stomach of the baobab tree,

you must leave the better part for the spirit of the tree, and then share the remnant sweetness

with your neighbors. And what they say, among the reeds, what they say, in the arms of the trees,

what they say in the shelter of the sky, that is enough for the days of terror and sorrow. Amen.

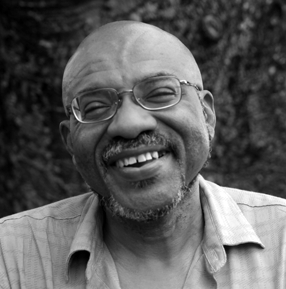

Copyright © 2021 by Kwame Dawes. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on February 18, 2021, by the Academy of American Poets

“‘How I Pray in the Plague’ is a meditation on the phrase attributed to Christ, ‘Lead us not into temptation.’ This meditation, as I suppose is true of most meditations, does not lead to answers or relief. In the plague, prayer, like poetry, is the honey I give back to the source of poetry or the impulse to prayer, and hopefully, the sweetness that I share with my neighbors.”

—Kwame Dawes