The Habit of Perfection

Elected Silence, sing to me

And beat upon my whorlèd ear,

Pipe me to pastures still and be

The music that I care to hear.

Shape nothing, lips; be lovely-dumb:

It is the shut, the curfew sent

From there where all surrenders come

Which only make you eloquent.

Be shellèd, eyes, with double dark

And find the uncreated light:

This ruck and reel which you remark

Coils, keeps, and teases simple sight.

Palate, the hutch of tasty lust,

Desire not to be rinsed with wine:

The can must be so sweet, the crust

So fresh that come in fasts divine!

Nostrils, our careless breath that spend

Upon the stir and keep of pride,

What relish shall the censers send

Along the sanctuary side!

O feel-of-primrose hands, O feet

That want the yield of plushy sward,

But you shall walk the golden street

And you unhouse and house the Lord.

And, Poverty, be thou the bride

And now the marriage feast begun,

And lily-coloured clothes provide

Your spouse not laboured-at nor spun.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on January 14, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

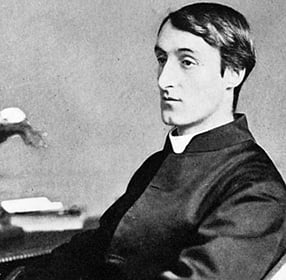

Originally written in 1866, a fragment from “The Habit of Perfection” was first published in Robert Seymour Bridges’s anthology The Spirit of Man: An Anthology in English & French from the Philosophers & Poets (Longmans Green & Co., 1916). In “Food Metaphors in Gerard Manley Hopkins,” published in Victorian Poetry, vol. 55, no. 3 (Fall 2017), Mariaconcetta Costantini, professor of English at D’Annunzio University of Chieti–Pescara, Italy, writes, “Another struggle against the lure of the senses, including taste, is dramatized in ‘The Habit of Perfection.’ Like other lyrics of Hopkins’s university years, this poem in quatrains exalts the human capacity for renouncing physical pleasures in favor of spiritual ones [. . .]. [T]he poet turns the body and its perceptive organs into vehicles for achieving a condition of bliss that entails the final rejection of corporeality. Such a strategy is evident at the beginning of each quatrain, which opens with a direct reference to man’s sensual powers of perception / communication: hearing, speaking, seeing, tasting, smelling and touching. Stanza four, in particular, focuses on the pleasures of the palate—‘the hutch of tasty lust’—which are visibly evoked before the invitation to transcend them. Despite the use of negation, the speaker gives flesh to the palate’s ‘desire . . . to be rinsed with wine,’ while the other references to drinks and aliments (‘The can . . . so sweet, the crust / So fresh’) attach physical valences to the ‘fasts divine.’”