Grandfather

grand·fa·ther. (noun) 1. the father of one’s father or mother: As in, my father’s father, my grandfather, sharecropped on a farm in Midway, AL. Angry all the time, he fled to Ohio for cleaner work, but the same dirt beat him down through his day. 2. the person who founded or originated something: In 1832, Thomas D. Rice, grandfather of Jim Crow, popularizes the phrase with a song of same name, dancing and singing in blackface, to play a trickster figure, without the wisdom of Anansi, but “nah, uh-uh, nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah,” was all black people heard when he sang his song.

grand·fa·ther. (verb) [with object] 1. North American informal exempt (someone or something) from a new law or regulation: Landowners, who stole land from indigenous people before the Federal Land Policy and Management Act struck this behavior down in 1976, have been grandfathered in to keep these hallowed grounds. Grandfathered in, their children’s children also can keep the land. Those from whom land was stolen, those who were raided, raped, and run out of town—Greenwood, OK; Eatonville, FL; Wilmington, NC; Vicksburg, MS; etc. —leaving their homes behind, have been grandfathered in to continue looking for a place to feel safe to call home. 2. to permit to continue under a grandfather clause: As in, to pass down privilege, which is grandfathered in the blood of law, passed down, grandfathered in speech to mean passed down to continue but not to offend just to understand, with your grandfather and with mine, passed from one kin to another, no fault of mine, just passed past your grandfather to mine to me, just law, just an idiom of life, you understand; we all started the same and no grandfathering of my grandfather bears down on you, maybe just on your grandfather, son.

Copyright © 2022 by A. Van Jordan. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on December 7, 2022, by the Academy of American Poets.

“This poem emerged after I heard the phrase ‘grandfathered in’ twice in one day and realized that the people using it had no idea of its historical context, particularly while talking to a Black person. It’s one of those phrases that gets used blithely, but, increasingly, over time, I’m losing my patience for it.”

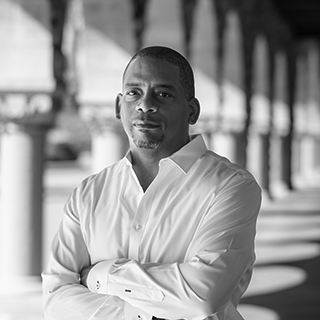

—A. Van Jordan