Fête Gallante

translated by Richard Aldington

The Morning Star flies from the clouds and the bird cries to the dawn.

Amaryllis, awake! Lead your snowy sheep to pasture while the cold grass glitters with white dew.

To-day I will pasture my goats in a shady valley, for later it will be very hot.

Among those distant hills lies a very great valley cut by a fair stream.

Here there are cold rills and soft pasture and the kind wind engenders many-coloured flowers.

Dear, there I shall be alone, and if you love me, there you will come alone also.

Lusus Pastorales continens (IV)

Jam fugat humentes formosus Lucifer umbras,

Et dulci Auroram voce salutat avis;

Surge, Amarylli, greges niveos in pascua pelle,

Frigida dum cano gramina rore madent.

Ipse meas hodie nemorosa in valle capellas

Pasco, namque hodie maximus æstus erit.

Scis ne Menandrei fontem, & vineta Galefi?

Et quæ formosus rura Lycambus habet?

Hos inter colles recubat viridissima silva,

Quam pulcher liquido Mesulus amne secat:

Nec gelidi fontes absunt, nec pabula læta,

Et varios flores aura benigna parit.

Illic te maneo solus, carissima Nympha:

Si tibi sum carus, tu quoque sola veni.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on September 11, 2022, by the Academy of American Poets.

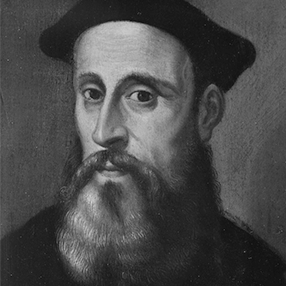

“Fête Gallante” was originally composed in Renaissance Latin and collected in Marcantonio Flaminio’s Lusus Pastorales. Later it was translated into English prose by Richard Aldington and published in The Egoist vol. 3, no. 12 (December 1916), and then collected in Aldington’s Latin Poems of the Renaissance (The Egoist Press, 1919). In a note included with his translations of Flaminio’s poems in The Egoist, Aldington writes that the translations “were written at odd moments in the somewhat noisy and unfavourable [sic] surroundings of a barrack-room,” suggesting that he composed them during his military service in World War One. Remarking on the titling conventions of Aldington’s translations, scholar Marguerite S. Murphy writes, in “What Titles Tell Us: The Prose Poem in the Little Magazines of Early Modernism,” that Aldington’s titles, which deviate from the source material in favor of generic ones, “situate the origin of these poems in a somewhat obscure past, making the act of translation a revival of a presumably little known or nearly forgotten tradition.” Quoted elsewhere in Murphy’s essay, Ezra Pound writes, regarding the practice of translating verse into prose, that “[b]eyond its external symmetry, every formal poem should have its internal thought-form, or at least, thought progress. This form can, of course, be as well displayed in a prose version as in a metrical one.” In “M. Antonius Flamininus and John Keats: A Kinship in Genius,” an essay in which Pound himself compares Marcantonio Flaminio to Keats, he writes that his poetry is “no dead classicism; it is pastoral unspoiled by any sham beauty. He is alive to the real people as well as to the spirits of the pools and trees.”