This Evening Let’s

not talk

about my country How

I’m from an optimistic culture

that speaks louder than my passport

Don’t double-agent-contra my

invincible innocence I’ve

got my own

suspicions Let’s

order retsina

cracked olives and bread

I’ve got questions of my own but

let’s give a little

let’s let a little be

If friendship is not a tragedy

if it’s a mercy

we can be merciful

if it’s just escape

we’re neither of us running

why otherwise be there

Too many reasons not

to waste a rainy evening

in a backroom of bouzouki

and kitchen Greek

I’ve got questions of my own but

let’s let it be a little

There’s a beat in my head

song of my country

called Happiness, U.S.A.

Drowns out bouzouki

drowns out world and fusion

with its Get—get—get

into your happiness before

happiness pulls away

hangs a left along the piney shore

weaves a hand at you—“one I adore”—

Don’t be proud, run hard for that

enchantment boat

tear up the shore if you must but

get into your happiness because

before

and otherwise

it’s going to pull away

So tell me later

what I know already

and what I don’t get

yet save for another day

Tell me this time

what you are going through

traveling the Metropolitan

Express

break out of that style

give me your smile

awhile

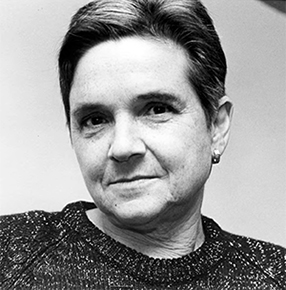

From The School Among the Ruins: Poems 2000–2004 by Adrienne Rich. Copyright © 2004 by Adrienne Rich. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

“This Evening Let’s” appears in The School Among the Ruins: Poems 2000–2004 (W. W. Norton, 2004) by Adrienne Rich. In her essay, “Blood, Bread, and Poetry: The Location of the Poet,” published in The Massachusetts Review (Autumn 1983), Rich wrote: “I write for the still-fragmented parts in me, trying to bring them together. Whoever can read and use any of this, I write for them as well. I write in full knowledge that the majority of the world’s illiterates are women, that I live in a technologically advanced country where forty percent of the people can barely read and twenty percent are functionally illiterate. [. . .] Because I can write at all—and I think of all the ways women especially have been prevented from writing—because my words are read and taken seriously, because I see my work as part of something larger than my own life or the history of literature, I feel a responsibility to keep searching for teachers who can help me widen and deepen the sources, and examine the ego that speaks in my poems—not for political ‘correctness’ but for ignorance, solipsism, laziness, dishonesty, automatic writing.”