From “Clarel” [The Hostel]

In chamber low and scored by time,

Masonry old, late washed with lime—

Much like a tomb new-cut in stone;

Elbow on knee, and brow sustained

All motionless on sidelong hand,

A student sits, and broods alone.

The small deep casement sheds a ray

Which tells that in the Holy Town

It is the passing of the day—

The Vigil of Epiphany.

Beside him in the narrow cell

His luggage lies unpacked; thereon

The dust lies, and on him as well—

The dust of travel. But anon

His face he lifts—in feature fine,

Yet pale, and all but feminine

But for the eye and serious brow—

Then rises, paces to and fro,

And pauses, saying, “Other cheer

Than that anticipated here,

By me the learner, now I find.

Theology, art thou so blind?

What means this naturalistic knell

In lieu of Siloh’s oracle

Which here should murmur? Snatched from grace,

And waylaid in the holy place!

Not thus it was but yesterday

Off Jaffa on the clear blue sea;

Nor thus, my heart, it was with thee

Landing amid the shouts and spray;

Nor thus when mounted, full equipped,

Out through the vaulted gate we slipped

Beyond the walls where gardens bright

With bloom and blossom cheered the sight.

“The plain we crossed. In afternoon,

How like our early autumn bland—

So softly tempered for a boon—

The breath of Sharon’s prairie land!

And was it, yes, her titled Rose,

That scarlet poppy oft at hand?

Then Ramleh gleamed, the sail-white town

At even. There I watched day close

From the fair tower, the suburb one:

Sewaward and dazing set the sun:

Inland I turned me toward the wall

Of Ephraim, stretched in purple pall.

Romance of mountains! But in end

What change the near approach could lend.

“The start this morning—gun and lance

Against the quarter-moon’s low tide;

The thieves’ huts where we hushed the ride;

Chill day-break in the lorn advance;

In stony strait the scorch of noon,

Thrown off by crags, reminding one

Of those hot paynims whose fierce hands

Flung showers of Afric’s fiery sands

In face of that crusader-king,

Louis, to whither so his wing;

And, at the last, aloft for goal ,

Like the ice-bastions round the Pole,

Thy blank, blank towers, Jerusalem!”

Again he droops, with brow on hand.

But, starting up, “Why, well I knew

Salem to be no Samarcand;

‘Twas scarce surprise; and yet first view

Brings this eclipse. Needs be my soul,

Purged by the desert’s subtle air

From bookish vapors, now is heir

To nature’s influx of control;

Comes likewise now to consciousness

Of the true import of that press

Of inklings which in travel late

Through Latin lands, did vex my state,

And somehow seemed clandestine. Ah!

These under-formings in the mind,

Banked corals which ascend from far,

But little heed men that they wind

Unseen, unheard —till lo, the reef—

The reef and breaker, wreck and grief.

But here unlearning, how to me

Opes the expanse of time’s vast sea!

Yes, I am young, but Asia old.

The books, the books not all have told.

“And, for the rest, the facile chat

Of overweenings—what was that

The grave one said in Jaffa lane

Whom there I met, my countryman,

But new-returned from travel here;

Some word of mine provoked the strain;

His meaning now begins to clear:

Let me go over it again:—

“Our New World’s worldly wit so shrewd

Lacks the semitic reverent mood,

Unworldy—hardly may confer

Fitness for just interpreter

Of Palestine. Forego the state

of local minds inveterate,

Tied to one poor and casual form.

To avoid the deep saves not from the storm.

“Those things he said, and added more;

No clear authenticated lore

I deemed. But now, need now confess

mu cultivated narrowness,

Though scarce indeed of sort he meant?

‘Tis the uprooting of content!”

So he, the student. ’Twas a mind,

Earnest by nature, long confined

Apart like Vesta in a grove

Collegiate, but let to rove

At last abroad among mankind,

And here in end confronted so

By the true genius, friend, or foe,

And actual visage of a place

Before but dreamed of in the glow

Of fancy’s spiritual grace.

Further his meditations aim,

Reverting to his different frame

Bygone. And then: “Can faith remove

Her light, because of late no plea

I’ve lifted to her source above?”

Dropping thereat upon the knee,

His lips he parted; but the word

Against the utterance demurred

And failed him. With infirm intent

He sought the house-top. Set of sun:

His feet upon the yet warm stone,

He, Clarel, by the coping leant,

In silent gaze. The mountain town,

A walled and battlemented one,

With houseless suburbs front and rear,

And flanks built up from steeps severe,

Saddles and turrets the ascent—

Tower which rides the elephant.

Hence large the view. There where he stood,

Was Acra’s upper neighborhood.

The circling hills he saw, with one

Excelling, ample in its crown,

Making the uplifted city low

By contrast—Olivet. The flow

of eventide was at full brim;

Overlooked, the houses sloped from him—

Terraced or domed, unchimnied, gray,

All stone—a moor of roofs. No play

Of life; no smoke went up, no sound

Except low hum, and that half drowned.

The inn abutted on the pool

Named Hezekiah’s, a sunken court

Where silence and seclusion rule,

Hemmed round by walls of nature’s sort,

Base to stone structures seeming one

E’en with the steep’s they stand upon.

As a three-decker’s stern-lights peer

Down on the oily wake below,

Upon the sleek dark waters here

The inn’s small lattices bestow

A rearward glance. And here and there

In flaws the languid evening air

Stirs the dull weeds adust, which trail

In festoons form the crag, and veil

The ancient fissures, overtopped

By the tall convent of the Copt,

Built like a light-house o’er the main.

Blind arches showed in the walls of wane,

Sealed windows, portals masoned fast,

And terraces where nothing passed

By parapets all dumb. No tarn

Among the Kaatskills, high above

Farm-house and stack, last lichened barn

And log-bridge rotting in remove—

More lonesome looks than this dead pool

In town where living creatures rule.

Not here the spell might he undo;

The strangeness haunted him and grew.

But twilight closes. He descends

And toward the inner court he wends.

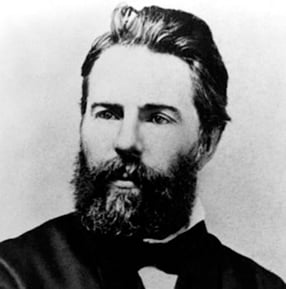

From Clarel: A Poem, and a Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1876) by Herman Melville. This poem is in the public domain.