To a Certain Lady, in Her Garden

Lady, my lady, come from out the garden,

Clayfingered, dirtysmocked, and in my time

I too shall learn the quietness of Arden,

Knowledge so long a stranger to my rhyme.

What were more fitting than your springtime task?

Here, close engirdled by your vines and flowers

Surely there is no other grace to ask,

No better cloister from the bickering hours.

A step beyond, the dingy streets begin

With all their farce, and silly tragedy—

But here, unmindful of the futile din

You grow your flowers, far wiser certainly,

You and your garden sum the same to me,

A sense of strange and momentary pleasure,

And beauty snatched—oh, fragmentarily

Perhaps, yet who can boast of other seizure?

Oh, you have somehow robbed, I know not how

The secret of the loveliness of these

Whom you have served so long. Oh, shameless, now

You flaunt the winnings of your thieveries.

Thus, I exclaim against you, profiteer. . . .

For purpled evenings spent in pleasing toil,

Should you have gained so easily the dear

Capricious largesse of the miser soil?

Colorful living in a world grown dull,

Quiet sufficiency in weakling days,

Delicate happiness, more beautiful

For lighting up belittered, grimy ways—

Surely I think I shall remember this,

You in your old, rough dress, bedaubed with clay,

Your smudgy face parading happiness,

Life’s puzzle solved. Perhaps, in turn, you may.

One time, while clipping bushes, tending vines,

(Making your brave, sly mock at dastard days,)

Laugh gently at these trivial, truthful lines—

And that will be sufficient for my praise.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on February 10, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

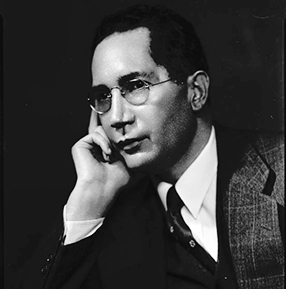

“To a Certain Lady, in Her Garden” appeared in Countee Cullen’s anthology Caroling Dusk (Harper & Brothers, 1927). In “Sterling Brown’s Poetic Ethnography: A Black and Blues Ontology,” published in Callaloo, vol. 21, no. 4 (Autumn 1998), Beverly Lanier Skinner, former associate professor of English at Millersville University, writes, “[Sterling A. Brown’s] poems written in ‘literary English and form’ are translations into standard English of the same black and blues ontology that [his] vernacular and folk-based poems express in code. [. . .] [One] Standard English poem, ‘To a Certain Lady, in Her Garden’ translates playfully—in total disregard of the challenging imperatives of survival for African Americans—how Black folk have lived quiet moments of their lives with joie de vivre. The poem shows those readers uninitiated in the lived experience of African Americans the triumph of simple joys and simple pleasures in complete disregard of a hegemonic presence [. . .]. This poem is an assertion of beauty and humanity that defies hasty generalization or stereotyping.”