Brothers

See! There he stands; not brave, but with an air

Of sullen stupor. Mark him well! Is he

Not more like brute than man? Look in his eye!

No light is there; none, save the glint that shines

In the now glaring, and now shifting orbs

Of some wild animal caught in the hunter’s trap.

How came this beast in human shape and form?

Speak, man!—We call you man because you wear

His shape—How are you thus? Are you not from

That docile, child-like, tender-hearted race

Which we have known three centuries? Not from

That more than faithful race which through three wars

Fed our dear wives and nursed our helpless babes

Without a single breach of trust? Speak out!

I am, and am not.

Then who, why are you?

I am a thing not new, I am as old

As human nature. I am that which lurks,

Ready to spring whenever a bar is loosed;

The ancient trait which fights incessantly

Against restraint, balks at the upward climb;

The weight forever seeking to obey

The law of downward pull—and I am more:

The bitter fruit am I of planted seed;

The resultant, the inevitable end

Of evil forces and the powers of wrong.

Lessons in degradation, taught and learned,

The memories of cruel sights and deeds,

The pent-up bitterness, the unspent hate

Filtered through fifteen generations have

Sprung up and found in me sporadic life.

In me the muttered curse of dying men,

On me the stain of conquered women, and

Consuming me the fearful fires of lust,

Lit long ago, by other hands than mine.

In me the down-crushed spirit, the hurled-back prayers

Of wretches now long dead—their dire bequests—

In me the echo of the stifled cry

Of children for their bartered mothers’ breasts.

I claim no race, no race claims me; I am

No more than human dregs; degenerate;

The monstrous offspring of the monster, Sin;

I am—just what I am. . . . The race that fed

Your wives and nursed your babes would do the same

Today, but I—

Enough, the brute must die!

Quick! Chain him to that oak! It will resist

The fire much longer than this slender pine.

Now bring the fuel! Pile it ’round him! Wait!

Pile not so fast or high! or we shall lose

The agony and terror in his face.

And now the torch! Good fuel that! the flames

Already leap head-high. Ha! hear that shriek!

And there’s another! Wilder than the first.

Fetch water! Water! Pour a little on

The fire, lest it should burn too fast. Hold so!

Now let it slowly blaze again. See there!

He squirms! He groans! His eyes bulge wildly out,

Searching around in vain appeal for help!

Another shriek, the last! Watch how the flesh

Grows crisp and hangs till, turned to ash, it sifts

Down through the coils of chain that hold erect

The ghastly frame against the bark-scorched tree.

Stop! to each man no more than one man’s share.

You take that bone, and you this tooth; the chain—

Let us divide its links; this skull, of course,

In fair division, to the leader comes.

And now his fiendish crime has been avenged;

Let us back to our wives and children.—Say,

What did he mean by those last muttered words,

“Brothers in spirit, brothers in deed are we”?

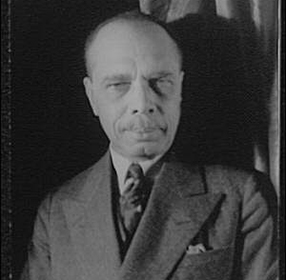

From The Book of American Negro Poetry (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922), edited by James Weldon Johnson. This poem is in the public domain.