Breath

Who hears the humming

of rocks at great height,

the long steady drone

of granite holding together,

the strumming of obsidian

to itself? I go among

the stones stooping

and pecking like a

sparrow, imagining

the glacier’s final push

resounding still. In

a freezing mountain

stream, my hand opens

scratched and raw and

flutters strangely,

more like an animal

or wild blossom in wind

than any part of me. Great

fields of stone

stretching away under

a slate sky, their single

flower the flower

of my right hand.

Last night

the fire died into itself

black stick by stick

and the dark came out

of my eyes flooding

everything. I

slept alone and dreamed

of you in an old house

back home among

your country people,

among the dead, not

any living one besides

yourself. I woke

scared by the gasping

of a wild one, scared

by my own breath, and

slowly calmed

remembering your weight

beside me all these

years, and here and

there an eye of stone

gleamed with the warm light

of an absent star.

Today

in this high clear room

of the world, I squat

to the life of rocks

jewelled in the stream

or whispering

like shards. What fears

are still held locked

in the veins till the last

fire, and who will calm

us then under a gold sky

that will be all of earth?

Two miles below on the burning

summer plains, you go

about your life one

more day. I give you

almond blossoms

for your hair, your hair

that will be white, I give

the world my worn-out breath

on an old tune, I give

it all I have

and take it back again.

“Breath,” 1991 by Philip Levine; from New Selected Poems by Philip Levine. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

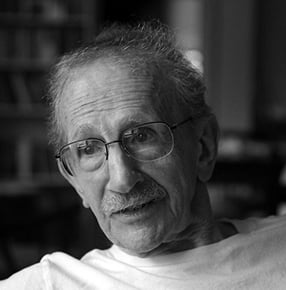

“Breath” by Philip Levine originally appeared in his poetry collection They Feed They Lion (MacMillan Publishing Company, 1972) and later in New Selected Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 1991). In his essay, “Where the Angels Come Toward Us: The Poetry of Philip Levine,” former Chancellor David St. John notes, “Just as Philip Levine chooses to give voice to those who have no power to do so themselves, he likewise looks in his poems for the chance to give voice to the natural world, taking—like Francis Ponge—the side of things, the side of nature and its elements. And Levine is in many ways an old-fashioned troubadour, a singer of tales of love and heroism. Though it comes colored by the music of his world, what Levine has to offer is as elemental as breath. It is the simple insistence of breath, of the will to live—and the force of all living things in nature—that Levine exalts again and again.”