For Black Children at the End of the World—and the Beginning

You are in the black car burning beneath the highway

And rising above it—not as smoke

But what causes it to rise. Hey, Black Child,

You are the fire at the end of your elders’

Weeping, fire against the blur of horse, hoof,

Stick, stone, several plagues including time.

Chrysalis hanging on the bough of this night

And the burning world: Burn, Baby, burn.

Anvil and iron be thy name, yea though ye may

Walk among the harnessed heat and huntsmen

Who bear their masters’ hunger for paradise

In your rabbit-death, in the beheading of your ghost.

You are the healing snake in the heather

Bursting forth from your humps of sleep.

In the morning, your tongue moves along the earth

Naming hawk sky; rabbit run; your tongue,

Poison to the filthy democracy, to the gold-

Domed capitols where the ‘Guard in their grub-

Worm-colored uniforms cling to the blades of grass—

Worm on the leaf, worm in the dust, worm,

Worm made of rust: sing it with me,

Dragon of Insurmountable Beauty.

Black Child, laugh at the men with their hoofs

and borrowed muscle, their long and short guns,

The worm of their faces, their casket ass-

Embling of the afternoon, leftover leaves

From last year’s autumn scraping across their boots;

Laugh, laugh at their assassins on the roofs

(For the time of the assassin is also the time of hysterical laughter).

Black Child, you are the walking-on-of-water

Without the need of an approving master.

You are in a beautiful language.

You are what lies beyond this kingdom

And the next and the next and fire. Fire, Black Child.

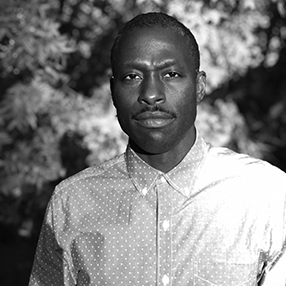

Copyright © 2020 by Roger Reeves. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 16, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

“‘I don’t want the police to shoot me,’ said L—, a friend’s five-year-old child, a little boy who was waiting in his parents car, waiting to participate in a socially-distant, car-caravan-protest that would snake its way through the South Austin streets, a protest aimed at the City Manager and the City Council’s recent deliberation over the police budget. Another friend’s child, a boy of eight, said the same thing while participating in a protest shortly after the murder of George Floyd, waving at snipers on the roof of the capitol building in hopes that if he waved, then snipers might not shoot him. Some of the snipers waved back. I realized that these black children must be accounted for, loved, considered in the middle of this moment of protesting, in the middle of this fight against white supremacy. I wrote this poem as a turn to them, to the black children that live in America and have lived in America. I wrote it for all of us.”

—Roger Reeves