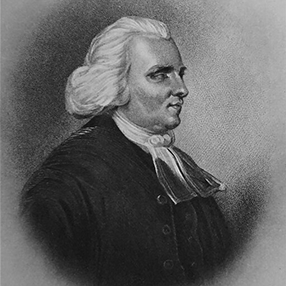

The Author’s Picture

While in my matchless graces wrapt I stand,

And touch each feature with a trembling hand;

Deign, lovely self! with art and nature’s pride,

To mix the colours, and the pencil guide.

Self is the grand pursuit of half mankind;

How vast a crowd by self, like me, are blind!

By self, the fop, in magic colours shown,

Tho’, scorn’d by ev’ry eye, delights his own:

When age and wrinkles seize the conqu’ring maid,

Self, not the glass, reflects the flatt’ring shade.

Then, wonder-working self! begin the lay;

Thy charms to others, as to me, display.

Straight is my person, but of little size;

Lean are my cheeks, and hollow are my eyes;

My youthful down is, like my talents, rare;

Politely distant stands each single hair.

My voice, too rough to charm a lady’s ear;

So smooth, a child may listen without fear;

Not form’d in cadence soft and warbling lays,

To sooth the fair thro’ pleasure’s wanton ways.

My form so fine, so regular, so new;

My port so manly, and so fresh my hue;

Oft, as I meet the crowd, they laughing say,

“See, see Memento Mori cross the way.”

The ravished Proserpine at last, we know,

Grew fondly jealous of her sable beau;

But, thanks to nature! none from me need fly;

One heart the devil could wound—so cannot I.

Yet, tho’ my person fearless may be seen,

There is some danger in my graceful mien:

For, as some vessel toss’d by wind and tide,

Bounds o’er the waves, and rocks from side to side;

In just vibration thus I always move:

This who can view, and not be forc’d to love?

Hail! charming self! by whose propitious aid

My form in all its glory stands display’d:

Be present still; with inspiration kind,

Let the same faithful colours paint the mind.

Like all mankind, with vanity I’m bless’d;

Conscious of wit I never yet possess’d.

To strong desires my heart an easy prey,

Oft feels their force, but never owns their sway.

This hour, perhaps, as death I hate my foe;

The next I wonder why I should do so.

Tho’ poor, the rich I view with careless eye;

Scorn a vain oath, and hate a serious lie.

I ne’er, for satire, torture common sense;

Nor show my wit at God’s, nor man’s expence.

Harmless I live, unknowing and unknown;

Wish well to all, and yet do good to none.

Unmerited contempt I hate to bear;

Yet on my faults, like others, am severe.

Dishonest flames my bosom never fire;

The bad I pity, and the good admire;

Fond of the muse, to her devote my days,

And scribble—not for pudding, but for praise.

These careless lines, if any virgin hears,

Perhaps, in pity to my joyless years,

She may consent a gen’rous flame to own,

And I no longer sigh the nights alone.

But, should the fair, affected, vain, or nice,

Scream with the fears inspir’d by frogs or mice;

Cry, Save us, heav’n! a spectre, not a man!

Her hartshorn snatch, or interpose her fan:

If I my tender overture repeat;

O! may my vows her kind reception meet!

May she new graces on my form bestow,

And, with tall honours, dignify my brow!

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on July 20, 2023, by the Academy of American Poets.

“Whole books should be written about this one poem! But for now, let us ask: why would the speaker tremble to touch himself? What I call Distantism, the privileging of the distance senses of hearing and vision, is not merely the regulation of social distance but goes beyond it in keeping us physically apart. Distantism intends to atomize us, to wrap us in tidy individual packets. It can separate us from ourselves. Yet Thomas Blacklock boldly offers his body, trembling hands notwithstanding. He achieves in ‘The Author’s Picture’ an exquisite equilibrium, equatorial in its wobbling sway. By turns self-deprecating and self-celebratory, Blacklock tackles his task with a joyous impudence. ‘My youthful down is, like my talents, rare,” the speaker jokes. ‘Politely distant stands each single hair.’ As wonderfully engaged with his own body as the speaker is, he is rightly not very interested in it—interested, yes, but not very. There’s so much more that makes a meaningful ‘picture.’ The speaker constantly fumbles his way out of the skin-encased body. One needs a world, a way to move, a geography, so that what we have is not a body, but, to use the philosopher Erin Manning’s terms, a ‘bodying,’ and not a world, but a ‘worlding.’”

—John Lee Clark